A short two years ago, the White House had high hopes for Haiti. It was a textbook case of a “transition to democracy”: an alliance between impoverished peasants and a liberal professional class toppled a military dictatorship, helped in part by the Roman Catholic Church and some prodding from Washington. There was to be an intermediate period of benign military rule, followed by free election and continued economic aid. Philippines, the sequel.

This rosy scenario remained central to U.S. for the next two years, even while it became increasingly clear that what was really under way was a transition to another form of dictatorship. Only six months ago, the assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs, Elliott Abrams, spoke glowingly of the “path to democracy” in Haiti. He pointed out that “the government, the election commission, the political parties, the churches, and other responsible democratic bodies have all expressed a willingness to keep the process moving forward through dialogue and a spirit of a common effort.” Even as late as November, the administration was confident enough to send representatives to the island for election day, accompanies by several hundred other international observers. Just before polling day, they were briefed by the American Embassy in Port-au-Prince. As one participant remarked, “Nothing prepared us at that meeting for what was to happen.” What happened was a bloodbath orchestrated by America’s supposed allies, the provisional government.

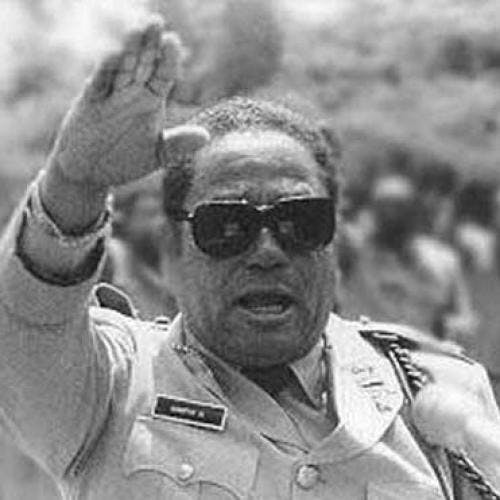

What went wrong? It’s not as if the administration did not foresee the difficulties. “I wouldn’t say [the suspension of elections] took us by surprise,” Abrams said afterward. “We were always aware of the dangers ad never thought the election was a sure thing.” Indeed, the State Department evidently was dubious of Henri Namphy all along, and for a while it took an appropriately firm line. Abrams said publicly in June that “some within the military and some representing the deposed clique seek to manipulate events in a way that would return Haiti to the feudal form of government [of] its Dubvalier presidents-for-life.” He threatened them, and again on July 9, to cut off U.S. aid if there was a “perversion of the democratic process.”

Yet throughout last year, as it became evident that the Namphy regime’s commitment to free elections was tentative at best, the administration was sending far softer signals. Despite the growing violence in Haiti, Abrams’s July comments were the last major public statement that real strings were attached to continued U.S. aid. On July 23 the Tontons Macoutes organized a massacre that claimed some 225 lives; on July 29 troops fired on 2,500 civilians protesting the Tontons Macoutes, killing eight and wounding 15; on October 13 presidential candidate Yves Volel was assassinated by plainclothes policemen; and on November 3 the electoral commission’s headquarters was firebombed.

At no point in this litany of atrocities was there a clear, high-level denunciation in Washington of the Haitian army’s involvement and its growing complicity in the breakdown of law and order. On the contrary, in October Abrams actually abandoned his hard-lined position. In Time, in a letter to the editor, he wrote: “While mistakes have been made, the CNG [the provisional government] has contributed importantly to laying the groundwork for a new, more democratic Haiti.”

It is clear not that such a low-key strategy was disastrous. Stephen Horblitt, a Haitian expert and aide to Delegate Walter Fauntroy, argues that Namphy’s maneuverings were part of a simple plan to test U.S. nerve: “The lack of clarity and commitment to back up what we wanted played a role in making the military believe they could get away with literally murder. They thought we’d back down, and they were right.”

Abrams denies this, saying that he sent private messages making it “crystal clear” tha the administration was serious. He defends his public statements that were supportive of Namphy: “A government official is an idiot is his attitude to a foreign government he’s trying to persuade is permanent attack.” And he believe the Namphy regime was planning on elections until the very last week, when fear of a radical victory in the elections prompted it to unleash the violence. According to this version of events, no U.S. pressure could have helped at this point: “You cannot ask a government to commit suicide to please the United States. We tried to persuade them that democracy wouldn’t necessarily threaten them, but we failed.”

But part of Namphy’s confidence lay in the long-term support the State Department had had given him, despite the fact that he was Duvalier’s first choice for successor and that he remained intensely loyal to the armed forces. The military was involved from the very beginning in activities fatal to Haitian democracy. According to Americas Watch, as early as March 1986 seven civilians ere shot dead and 19 beaten in a confrontation between a busload of civilians and an army captain; in April scores of unarmed civilians were killed by troops in a demonstration at Fort-Dimanche; abuses by the army, ranging from random seizure of land to arbitrary hostage-taking and killings continued throughout the year in the major cities. Gen. Williams Regala, minister of the interior and former head of Duvalier’s secret police reacted to the accusations by publicly announcing that there was nothing to investigate and that military actions were appropriate. A year later, with a mounting catalog of military offenses, the State Department argued that the army “has endeavored to prevent human rights abuses and corruption and has prosecuted a number of individuals. Freedom of speech and assembly are respected.” Military aid was not “lethal, designed to suppress free expression of ideas, and to nip democracy in the bud.” Thanks to U.S. aid, the number of Haitian military troops jumped from 6,500 in 1986 to 22,000 today.

This quiet U.S. support for Namphy was combined with what appears to have been blind optimism at the ambassadorial level. An Americas Watch report last November documented conclusive evidence that the military was likely to wreck the elections. But the embassy continued to report until election eve that such a result was not inevitable, and indeed risked the lives of dozens of foreign journalists and observers on election day with that assumption. There’s also evidence of amateurism According to Allen Wilde, Directory for thr Washington Office on Latin America, at the U.S. Embassyu briefing before the election one official, had not even of the Comité de Soutines, the leading group of liberal, professional Haitians helping to organize the elections.

The Administration’s initial reaction to this policy debacle has been one of damage control. The first major chance to pressure the Namphy regime was at a January 6 Barbados conference run by Caricom, the group representing English-speaking democracies in the region. The conference was due to affirm a package of tough sanctions against Haiti unless the January 17 elections were postponed a free election scheduled. But the Caricom communiqué, thanks largely to U.S. administration man Edward Seaga, prime minister of Jamaica, rejected sanction and kept open the possibility of recognizing a Haitian regime that emerge from the rigged election. Richard Holwill, deputy assistant secretary of state for the Caribbean, went to Barbados but failed to exert any pressure for action.

The White House has announced some sanctions—the end of $100 million in U.S. economic and military aid, the cutoff of some wheat supplies, and the withholding of some $50million in IMF money—but its disavowal of further action has destroyed the chance of future leverage. Economic pressure is ruled out because of its effect on the population, and a Venezuelan fuel-oil embargo was derailed by Csricom. Abrams describe any form of trade embargo as “exceptionally stupid”: “Do we want a with the people of Haiti? Do we want to wreck the industrial sector? Those factories and that investment which ahs been building up over the last five year won’t come back the day Haiti becomes a democracy.” Abrams now favors a policy of increasing foreign investment in the country along with quiet pressure behind the scenes. Constructive engagement, Haitian-style.

All the while, there’s been little discussion of the military options, despite the fact that the Haitian army, even with U.S. bolstering, is thought to be incapable of repeling a professional operation. It has never faced an external threat, is deeply divided, and relied on several key figures whose whereabouts are known to U.S. intelligence and who influence can almost entirely account for the recent disturbances. One would have thought that a discreet military operation designed to detain ringleaders, combined with an international peacekeeping for the direction of elections, would at least have been considered by this of all administrations. Yet it was dismissed out of hand within hours of Namphy’s coup. Abrams argues that even if a force could secure new elections, it would be difficult to leave a fragile civilian regime behind to face the military. “It doesn’t take guts—in fact the amount of military risk is minimal. The real question is: Is it in American interest to occupy Haiti for another 20 years?

Yet there’s plenty of evidence that the Namphy regime is sensitive to public pressure from the United States. Abrams’s July 9 statement threatening tough sanction prompted a swift government retreat from tits decree taking over the election from electoral commission. Some tough gesture is certainly overdue now. One independent agency official suggests that warship patrolling the coast could be enough to convince Namphy that the United States means business. On January 9 the Namphy regime showed that is still cares about world opinion when it made the cosmetic gesture of removing several Duvalierist from the electoral register.

But the administration isn’t listening. Last Saturday, in a front-page story in the New York Times, State Department official deliberately planyed down its chances of having any leverage at all. Now Abrams is all pragmatic resignation. The electoral commission is “A pretty disorganized group” and “a stable democracy in Haiti is difficult to achieve.” In other words, when it requires a real effort to achieve democracy in a non-communist impoverished country, this administration doesn’t really give s damn.