As you walk through the front door of the Columbia School of Journalism, the first thing you see is this paragraph, cast on a bronze plaque:

OUR REPUBLIC AND ITS PRESS WILL RISE OR FALL TOGETHER. AN ABLE, DISINTERESTED, PUBLIC-SPIRITED PRESS, WITH TRAINED INTELLIGENCE TO KNOW THE RIGHT AND COURAGE TO DO IT CAN PRESERVE THAT PUBLIC VIRTUE WITHOUT WHICH POPULAR GOVERNMENT IS A SHAM AND A MOCKERY. A CYNICAL, MERCENARY, DEMAGOGIC PRESS WILL PRODUCE IN TIME A PEOPLE AS BASE AS ITSELF. THE POWER TO MOULD THE FUTURE OF THE REPUBLIC WILL BE IN THE HANDS OF THE JOURNALISTS OF FUTURE GENERATIONS.

These four sentences are about as close to the intellectual origins of the American journalism school as you can get. They are taken from an article by Joseph Pulitzer in the May 1904 issue of the North American Review, the only serious defense he offered of his plan to fund the first journalism school at Columbia. He argued that his school would “raise journalism to the rank of a learned profession” and create a “class feeling among journalists.” He predicted—wrongly, as it turned out—that “before the century closes schools of journalism will be generally accepted as a feature of specialized higher education, like schools of law or of medicine,” and that the elites of Columbia would band together to cast out “the black sheep” from the profession.

According to his biographer, W.A. Swanberg, the idea of a school of journalism first dawned on Pulitzer in 1892, while he was confined to a dark room, suffering from asthma, insomnia, exhaustion, diabetes, manic-depression and failing eyesight. By the time he actually composed his thoughts for the North American Review, his bed chart included rheumatism, dyspepsia, catarrh and a bad case of shame for the Spanish atrocities in Cuba deliberately invented by his reporters to goose the circulation of his newspapers. His wife, a few of his colleagues and the trustees of Harvard and Columbia, who initially declined the $2 million sack dangled before them, suspected that he was not quite in his right mind. A New York newspaper editor named Horace White suggested that one might as well set up a graduate school in swimming. It took Pulitzer more than a decade to persuade Columbia to accept his money. Even then, the critics’ main question was never really answered: What would they teach at the Columbia Journalism School? A few weeks ago I went to find out.

The morning I arrived, the associate dean for academic affairs, Steven Isaacs, was putting his class through its paces. A masters of science in journalism requires about seven months of study. The first semester consists of core courses, including a course in ethics taught by Dean Isaacs. The second semester consists of electives with names such as “Developing a Personal Writing Style,” “Reporting on Ethical Issues in Science,” “Broadcast News: Content and Management” and “Research Tools.” The title of Isaacs’s course was “National Issues.”

The first morning session I attended was given over to an exercise designed to cultivate “the creative side to the thinking process,” according to the description in the course brochure. Isaacs removed a UCLA baseball cap from the head of a student named Karen Charman, placed it on the table in the middle of his classroom and told his students that they weren’t to leave until each had thought of 100 ideas for articles based on the UCLA cap. For the next two hours there was no sound in the room save for the clicking of the ancient radiator. By the end of the class all but one student had compiled a list of 100 ideas. The failure had come up with just fifty but argued that they were fifty especially good ones.

The next week Isaacs distributed the fruits of the exercise. They ran for ten pages, single-spaced, and began:

men wearing more hats as monoxidil fails

the rise of popularity of caps

baseball caps as appropriate head ware [sic], even for jogging presidents

the appropriate ways to wear a hat

Isaacs then moved from the conceptual to the practical: the actual act of composition. He assumed a position in the middle of the room beside an overhead projector, which beamed short, unsigned articles onto the wall. Isaacs had assigned the students to write sidebars to a New York Times article announcing the wedding of Rupert Murdoch’s daughter. They now loomed large before us. We read the various efforts while Isaacs, himself looming large in a brown suit and a Minneapolis Star baseball cap, swapped the pages in and out. Once we’d finished reading each piece, Isaacs, sounding like a gentle parody of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, offered advice about how not to write. Early on he had banned from student assignments the use of all adjectives and adverbs, as well as the verb “to be.” The students ceded the adjectives and adverbs, but struggled to preserve various forms of “to be,” which, after all, had served journalists nobly for centuries. Having lost the skirmish for “is,” they retreated and retrenched to defend “isn’t.” But Isaacs advanced mercilessly, and the class finally agreed to eliminate “isn’t,” “were,” “was,” and “has been” from their practice articles.

With a Magic Marker, Isaacs circled a passage in the piece under review. It read: “the term interracial is synonymous with marriages between blacks and whites.” “How do we fix this?” he asked.

“Equates with?” suggested a student.

“Uh-huh,” Isaacs said.

The article came down. “Now,” Isaacs continued, slapping another article onto the overhead projector, “what’s wrong here?”

Everyone looked a little uncomfortable. Ises, wases and has beens clotted the prose.

“Is?” someone offered.

“Aside from that,” Isaacs said.

The article under inspection concerned the disillusionment of male students at Vassar. (Murdoch’s daughter was a Vassar graduate.) Mainly, the piece consisted of a few limp quotes from a single source, a man who wished that he hadn’t attended Vassar. Its chief weakness was that it was entirely devoid of interest, probably even to the person who wrote it. Like most of the other pieces, it emitted a sad, dispirited, homework smell. Also, its author had several times confused “their” with “there,” and had split a pair of infinitives.

After a few unsuccessful guesses, the class gave up.

“Look again,” Isaacs said.

We all looked again.

“You don’t see it?” Isaacs asked.

We didn’t see it.

“Vassar,” he said.

We were dumfounded.

“She’s spelled Vassar with an e.”

There was a little gasp of silence. It was true. “Vasser” stared out at us, accusingly.

“Those of you who don’t own spell checkers, get one,” Isaacs bellowed. “Those nits! Those nits are what make the total. That’s what journalism is! It’s getting the details right. Get everything right! Precisely, 100 percent right. If you can’t get everything right, you better question whether this is the right place for you. As Flaubert said, God is in the details.”

Actually, he didn’t. Mies van der Rohe did. Flaubert, if he said anything close, said God is in the good details, although even that never has been verified. Isaacs went uncorrected, however, which is one of the advantages of being a dean instead of a journalist. Just about every student was preoccupied with the terrible fear that the woman in the front row who had been shifting around in her seat throughout the ruthless indictment of the unsigned piece was actually going to admit to having written it. Each time she motioned with her hand a silent brain-scream filled the room.

“O.K., I admit it,” she finally said. “It’s mine. I must have hit the return button, like F3, when I ran the spell check.”

“O.K.,” Isaacs said.

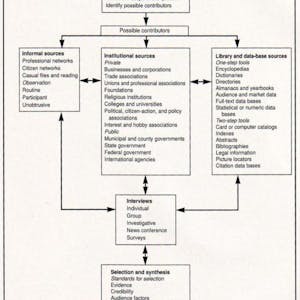

With a nip here and a tuck there, the inadequately schooled journalist could easily make the Columbia School of Journalism sound like a seven-month extension of this anecdote. Perhaps I am that journalist. The essential point here is that the desperate futility of journalism instruction becomes clearer the closer one gets to the deed. At journalism school, one does not simply report a story. One develops a “search strategy for mass communication” (see chart above). The principal text used at Columbia, in a section called “Truth Telling,” offers the mathematical formula: Story=Truth + X. “The story is never the full truth,” it intones. “There is always an X, a missing ingredient. Actually there is not an X but a series -- X1,X2,X3,X4....” This sort of irrelevant blather infects the entire curriculum. Here, for instance, is how the Columbia course bulletin describes one of the two main core courses, “Critical Issues in Journalism”:

With a nip here and a tuck there, the inadequately schooled journalist could easily make the Columbia School of Journalism sound like a seven-month extension of this anecdote. Perhaps I am that journalist. The essential point here is that the desperate futility of journalism instruction becomes clearer the closer one gets to the deed. At journalism school, one does not simply report a story. One develops a “search strategy for mass communication” (see chart above). The principal text used at Columbia, in a section called “Truth Telling,” offers the mathematical formula: Story=Truth + X. “The story is never the full truth,” it intones. “There is always an X, a missing ingredient. Actually there is not an X but a series -- X1,X2,X3,X4....” This sort of irrelevant blather infects the entire curriculum. Here, for instance, is how the Columbia course bulletin describes one of the two main core courses, “Critical Issues in Journalism”:

The principal concerns troubling modern journalists are examined in both their ethical and historical contexts. Topics cover such themes as the ethical reverberations in using and being used by sources of news; the debate between lawyers and journalists over codifying standards of journalistic ethics; societal reverberations of stereotyping in terms of politics, gender, race, etc.; ethical considerations in the setting of the news agenda; yellow journalism then and now; implications of corporate giantism in media ownership on journalism; the ethical perils of “beat” reporting; uses and abuses of staging and dramatic reenactments.

The larger force at work here is the instinct to complicate. Those who run, and attend, schools of journalism simply cannot—or don’t want to—believe that journalism is as simple as it is. The textbooks, the jargon, the spell checkers—the entire pretentious science of journalism only distract from the journalist’s task: to observe, to question, to read and to write about subjects other than journalism. They have less to do with writing journalism than avoiding having to write journalism at all.

It turns out that I am not alone in this view. Despite ninety years of saturation marketing—there are now 414 American schools and departments of journalism, containing 150,000 students—the trade has somehow sustained a robust contempt for the credential. Though journalism schools promise that they will find jobs for their graduates—indeed, the entire enterprise is based on the premise that a journalism school degree translates into a desk in the newsroom—many of the people who currently occupy those desks don’t want to have anything to do with them.

“Whenever I hear someone went to journalism school I immediately assume they are inferior in one way or another,” says Joel Achenbach, who writes the “Why Things Are” column for The Washington Post. “All we do is ask questions and type and occasionally turn a phrase. Why do you need to go to school for that?” Post editor Katherine Boo agrees. “It’s just a huge hoax,” she says. “I think how you become a journalist is that you write. You don’t see any correlation between journalistic education and an ability to write a story. When you get a great piece, and you call the person to see who he is, he never says, ‘Oh I just came from journalism school.’”

Even among working journalists who themselves went to journalism school, praise is not always forthcoming. “There is nothing I regret more,” says Joseph Nocera, who spent two years at the journalism school at Boston University and now writes widely. “Two years that could have been spent actually learning something were instead spent at a glorified trade school—I still recall with a shudder the two weeks spent learning how to write an obit—except that this trade school cannot possibly teach you what you need to learn, because it is impossible to re-create the journalism environment in the classroom.”

The people who do the hiring in the newsrooms echo these sentiments. “A journalism degree doesn’t really carry much weight,” says Jeanne Fox-Alston, the Post’s newsroom recruiting director. “In fact, we are a little bit concerned when we see that someone has taken a lot of journalism classes.” “If you can write, then you can figure out how to write journalism,” says Peter Kovaks, the Metro editor for the New Orleans Times-Picayune. The headhunters at The New York Times put it even more bluntly. “It really doesn’t pull any weight,” says a staffer who works for Carolyn Lee, the assistant managing editor in charge of hiring at the Times. “All we care about is ability and experience.”

One could go on. When Dean Isaacs worked for The Washington Post, he himself used to discriminate against the people he now instructs. “I stopped hiring people from the Columbia Journalism School,” he says. “They thought their shit didn’t smell. They were a constant morale problem.” Now that he’s at the school, however, he says he understands the value of a journalism degree. “It teaches you a way of thinking.”

Journalism schools, of course, balk at being balked at. Last fall Columbia’s placement director boasted to students that 45 percent of the class of 1992 had found jobs or internships in journalism. Perhaps, but to appreciate that figure fully you must know that 50 percent of the class came to the school from full-time jobs in journalism. Another 20 percent had internships. Assuming the numbers provided by Columbia students and faculty are accurate, the journalism school redirected 25 percent of the class of 1992 into other occupations.

And the students, it would appear, are beginning to catch on. The evaluations filled out by the journalism students before last year’s graduation underscore the problem. Of course, there were a number of satisfied customers—“Excellent! I want to be an active alumnus”—as you would expect from an institution that bestows an award, prize or fellowship upon one in eight of its graduates. And a pair of untenured professors seem to touch their students profoundly: Samuel Freedman, who teaches a course in book writing, and Richard Blood, who teaches basic reporting but puts his fifteen students through a life-changingly rigorous program more like boot camp. (He also happens to believe that the school lacks any real standards: “There aren’t three or four of my colleagues who have any business being here,” he told me. “I’ll be kind. I’ll say half a dozen.”)

But many more of the students seem to have peered into their futures with dismay. Here’s a small sample of the evaluations: “I am totally disappointed with the whole program.” “I can’t believe I paid this much money [tuition at the Columbia program is $18,000] to come here and I can’t get help finding a job.” “The placement office was something of a joke, as there were only two or three recruiters who came, most from very specialized journalism (i.e., Baseball Weekly).” “The J-school is a farce. The emperor has no clothes.” “I find it outrageous that the placement director left in October and students were never formally notified a) that she was gone or b) about progress in the search for a replacement. We are adults who are paying your salaries ...” And so on.

In the absence of optimistic placement statistics the authorities at Columbia offer a more elaborate explanation of the benefits of their journalism degree: it may not help you right away, but it will help you down the road. “I spent a lot of the time telling people that no, no one is going to make you a foreign correspondent and send you abroad next year,” says Judith Serrin, the placement director who left Columbia a year and a half ago. “What I used to say is that people who are out five years make these jumps.” The school seems to have settled on this story. Seven students and two professors cited the figure for me, unsolicited. Five years. Big jump. The belief in mysterious yet imminent career jumps has the advantage of being impossible to disprove without the benefit of a team of researchers. Enough able, driven people pass through Columbia and proceed to greater glory to sustain the myth. The question, impossible to answer, is whether they would have made the big jump on their own anyway

Explanations for the big jump vary, but the consensus among the students is that it happens because of personal connections. “The majority of the people who come out of here and get jobs move up the ladder very quickly because of the network,” says a student named Ron Spingarn. “They know the right people.” Says another student: “They say the connections you make here are worth the money.” Pressed on how this happens, she says, “There is an amazing Ivy League door-opening thing that goes on when you mention Columbia.” One of her classmates, a scholarship student, adds, “It’s not what your grades are. It’s who do you know. What professors do you know?” The frenzy of student networking is apparent, especially to the faculty. “When I went up there to teach,” says a reporter for The New York Times, “it was clear to me that the main reason [people attended] was that the students wanted to meet someone who worked at The New York Times.”

A few weeks ago, toward the end of the first semester of classes, about thirty journalism students assembled in the third-floor student lounge to compile a list of complaints about the school, which they eventually presented to Dean Joan Konner. They were busily agreeing that the school needed more Hispanics, more scholarship money for African Americans, a more culturally sensitive faculty and more awareness about AIDS, when a stranger crept in and took a seat. The stranger must have liked what he saw: all these prosperous-looking youths so preoccupied with their problems that they were blind to the events right in front of their eyes. Unnoticed, the stranger rifled through a student’s purse. The lounge wasn’t much bigger than a squash court, so he deserves some sort of prize for audacity.

It was only when the stranger made for the door that one of the students—the woman who’d been robbed—finally noticed him and shouted. The stranger raced out the door, down the stairwell, past the bronze plaque, past the bronze busts of Joseph Pulitzer, past the stucco reliefs of the Gods of Journalism and out into the night, chased by a dozen or so less swift journalism students. Standing near the fateful spot in the lounge where she and her classmates had been sitting, Kaue Noel Kelch-Mattox related the story to me. “We were literally ten to fifteen seconds behind him, but then he just disappeared,” she said. “I never would have thought this sort of thing could happen in my own student lounge.”

“Who wrote the story?” I asked. The students were required to hand in homework articles each week. The student newspaper was also sorely in need of material.

“No one,” she said. “There wasn’t a story.”

As I pulled out a pad and began to write, students in the lounge gathered around me, along with a pair of young adjunct professors.

“Oh, here comes the notebook!” said one, sounding very media wise.

“What’s your nut graph?” asked the other, who was keen to know how this article was going to turn out. I scribbled a note to check the meaning of the phrase, one of the several bits of J-school jargon I failed to understand.

“What happened to the wallet?” I asked my source.

“Why are you trying to find out?” she asked.

“I’m just curious.”

“O.K.” She looked relieved. “Then there’s not a story.”

“Yeah,” said one of the other students, a little aggressively. “It’s just normal here. I keep mugger money in one pocket and my money in the other.”

“Oh no,” said the media-wise professor, “what you’re going to see in this article is a completely skewed position on the crime problem in the school.”

The women telling the tale began to lecture me. “So, like, just because someone had their purse stolen is proof that there is something wrong with our school?”

“C’mon,” said the other professor, “tell us your nut graph.”

I gave up and dropped the pad. “What’s a nut graph?” I asked.

“He doesn’t know what a nut graph is!” someone shouted.

The adjunct professor took pity. He tried again, gently. “In the article you are writing about the school,” he said. “What’s your null hypothesis?”

My null hypothesis?

My null hypothesis! My angle. My bias. My take. My ... point ... of ... view!

“My null hypothesis,” I said, “is that the Columbia Journalism School is all bullshit.”

They paused. “That’s a good null hypothesis,” said one, finally.

Journalism schools are not alone in their attempts to dignify a trade by tacking onto it the idea of professionalism and laying over it a body of dubious theory. After all, McDonald’s Hamburger U. now trains Beverage Technicians. But the journalist’s role is precisely to cut through this sort of obfuscation, not to create more of it. The best journalists are almost the antithesis of professionals. The horror of disrepute, the preternatural respect for authority and the fear of controversy that so benefit the professional are absolute handicaps for a journalist. I doff my cap to those who have survived the experience of journalism school and still write good journalism. They deserve every Distinguished Alumni Award they receive, and more.

The first sentence on the bronze plaque that you see when you walk through the front door of the Columbia Journalism School may or may not be true, but it sets a fittingly autocratic, unreflective tone. The second sentence is ungrammatical. The last two sentences offer the sort of grandiose vision of journalism entertained mainly by retired journalists or those assigned to deliver speeches before handing out journalism awards. Highly flattering to all of us, of course, but it would be more true to flip the statement to read: “a cynical, mercenary, demagogic people will produce in time a press as base as itself ...” There’s also a small problem: when the journalism school cemented the bronze plaque on the wall in 1962, to commemorate its fiftieth anniversary, it misquoted the text as it appeared in its final, pamphlet form. Those nits! The details! Flaubert! A word of Joseph Pulitzer’s is missing, between demagogic and press. The word is CORRUPT.

This article originally appeared in the April 18, 1993 issue of magazine.