This article was originally published May 25, 1953.

The Enormous Radio and Other Stories

by John Cheever

(Funk and Wagnall's; 13.50)

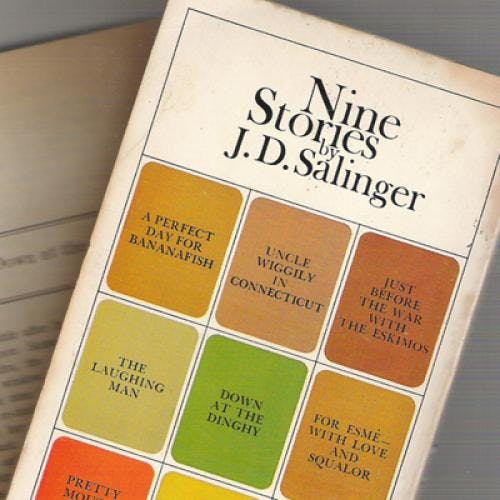

Nine Stories

by J. D. Salinger

(Little, Brown; $3).

Both these writers are New Yorker authors. It is fashionable, I gather, to be a little superior to the New Yorker story, and no one would want to maintain that making a living writing for The New Yorker would in the long run be the best thing that could happen to a talented man like Mr. Salinger. But I suspect the New Yorker's standards are better than we admit; they set high requirements of observation, understanding, and composition. If their limitations on subject matter are in the long run dangerous to real talent, they nonetheless provide a stiff course in the craft.

Mr. Cheever, for example, is not a writer of any great talent, but the stories in his book are all skillfully worked out and loaded with carefully observed manners. Congreve, who might, for a while at least, have been a great success in the New Yorker, once remarked that he selected a moral and then designed a fable to fit it. It seems unlikely, though great works have been written in even queerer ways than that. It is the glaring fault of Mr. Cheever's stories that they all appear to have been produced in that way. He does not so much imagine experience as have clever ideas for stories. There are the ingenious camera-angles, the elevator operators (two of these) and the apartment-house superintendents, very cute and innocent and staring wide-eyed at quality folk. There are the neat discoveries of commonplace morals in sophisticated lives. When Mr. Cheever tries for the big idea, his stories waver toward a formally — and therefore morally — ambiguous melodrama, as in "Torch Song" where a girl who appears, magically, never to grow old (shades of Dorian Gray) turns out to love dying people, or in "O City of Broken Dreams," where a pair of hicks who are said to be from Indiana but are really from Ring-Lardner-land are fantastically diddled by blase theatrical people. These are the stories of a clever short-story manufacturer, a man who has ideas about experience but has never known these ideas in experience. Their language and technique are highly refined; their feeling is crude. They are as well-made as any conscientious editor could demand; you cannot blame the doctor for their having been born with a very minimum of vitality.

Mr. Salinger is an altogether different matter. For all the prejudices against short stories, his Nine Stories has made the best-seller lists. This is — as things so seldom are — as it ought to be for Mr. Salinger is a talented writer. Even if this success is a mere by-product of The Catcher in the Rye, it is rough justice; for all its brilliance. The Catcher in the Rye does not quite come off as a whole; the best of these stories do. They have, as the novel did not, a controlling intention which is at once complex enough for Mr. Salinger's awareness and firm enough to give it a purpose. You suspect that the hovering presence, if not the actual blue pencil of a New Yorker editor had something to do with this, for the controlling intention is obviously the most difficult part of a story for Mr. Salinger, so that when he is not at his best he substitutes for it brilliant detail, as in The Catcher in the Rye, or a plot trick, as at the end of "Teddy." In fact, though it is a dangerous, perhaps even impertinent speculation, I would guess that Mr. Salinger's special gift for offcenter visions of experience comes from a kind of displacement of the imagination which makes it particularly difficult for him to conceive any unifying intention. The price he pays for his training is the occasional trick story, like "Pretty Mouth and Green My Eyes." Even the gimmicks are with Mr. Salinger hair raising, however, and this story gives its trick an extra Charles Addams twist at the end. In the best stories, where Mr. Salinger's talent remains unfrustrated, the discipline imposed by writing for The New Yorker is sheer gain; "A Perfect Day for Banahafish," "De Daumier- Smith's Blue Period," and large units of several other stories are better than anything in The Catcher in the Rye. It would be hard to say with them whether the wonderful detail or the way this detail is subordinated to the central insight is the more impressive. Perhaps the best thing about these stories is that though you feel the pleasure of both they do not separate in your mind.

For more TNR, become a fan on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.