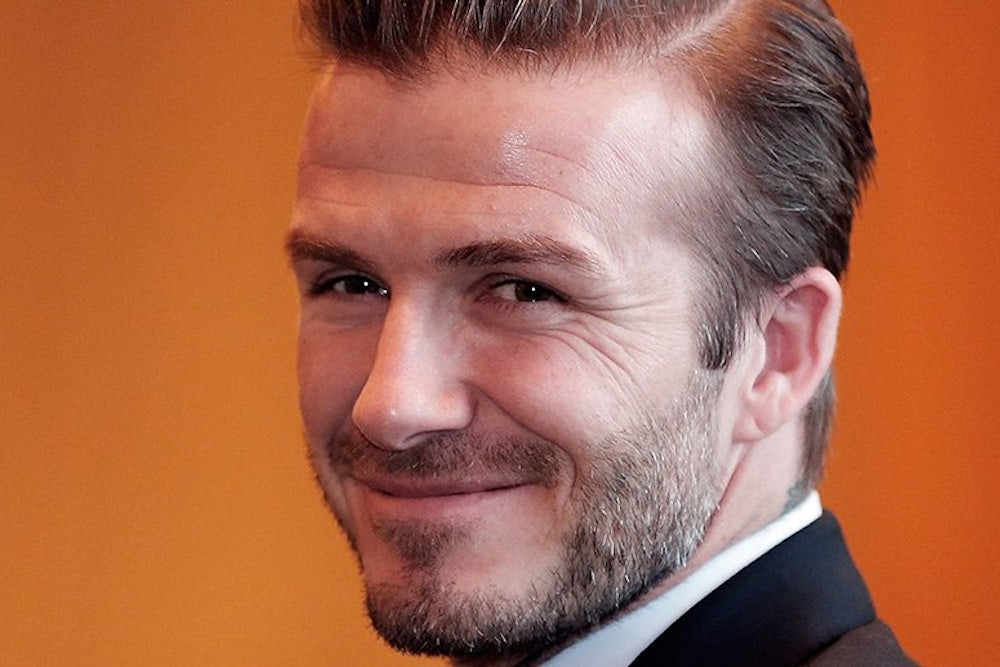

Why David Beckham sucks.

Saturday's Major League Soccer Cup between the Los Angeles Galaxy and Houston Dynamo marks David Beckham's final game in the league, which he joined five years ago for $250 million. Here's what we had to say about him back then.

George Best, arguably the greatest British soccer player of all time, once said of David Beckham: "He cannot kick with his left foot, he cannot head a ball, he cannot tackle, and he does not score many goals. Apart from that, he's all right." Best minced his words at a time when Beckham was a runner-up for the 1999 FIFA world player of the year and at the peak of his career, having successfully recovered from vilification following a mindless tantrum that led to his expulsion from a 1998 World Cup game against Argentina. Playing with a man short, England lost the game, being thus eliminated from the tournament. Beckham was widely blamed for the loss; indeed, the Daily Mirror printed a dartboard with a picture of him centered on the bullseye, while his effigy was hanged outside a London pub. But in 1999, Manchester United, his club, would win the English Premier League title, the F.A. Cup, and, to top it all, the European Champions League, and Beckham was instrumental in those achievements. At the time of Best's generous assessment, Beckham's star was as blindingly sparkling as ever, but Best managed to squint and see the truth beyond the glare.

And he was right, of course: Beckham—who you no doubt have heard has just joined the Los Angeles Galaxy of Major League Soccer for $250 million—leans on a golden right foot, capable of producing sublime crosses and free-kicks, but his range as a player has always been severely limited. On Sir Alex Ferguson's Manchester United team, Beckham's role as a right wing feeding the forwards was narrowly defined, and he was never allowed to stray from it. The team won when he and his mates stuck to the game plan, often enforced by the half-time "hair-dryer treatment"—Ferguson screaming in their faces. In 2003, they claimed another Premier title. It would be four years before David Beckham won anything again.

The cleats started coming off Beckham's Man U career after he married one Victoria Adams, commonly known at the time as Posh Spice, a member of the bimbo-band Spice Girls. The courtship of Beck and Posh—as they were lovingly called—had been a dream come true for the British tabloids, especially since the couple did not exactly try to escape the life of trashy celebrity. They sold the rights to cover their wedding to OK! Magazine and then put on a show: The wedding took place at Luttrellstown Castle, Ireland; cost about $1,000,000; required a staff of 437; and bore fruit in the shape of photos, published in every gossip rag, of Posh and Becks sitting on golden thrones.

Ferguson believed that the Beckham's life of celebrity and Victoria's rising influence over David, evident in his frequent hairstyle changes, were detrimental to the young lad's game and to team spirit. In 2000, Beckham missed training to care for Brooklyn, the Beckhams' first child, who was suffering from gastroenteritis. But that same night, Victoria posed for photographers at a London Fashion Week event, and Ferguson was hair-dryingly furious. Beckham's fame now exceeded his teammates', even if his performances started slacking. In 2003, after a defeat to London rivals Arsenal, Ferguson kicked a soccer shoe that struck Beckham above the eye, resulting in a cut that required two sutures. That summer, Beckham was offloaded to spending-crazy Real Madrid, building a squad of soccer stars bloated with greatness and uninterested in running, for whom making a fancy pass with a back heel would always be far more attractive than defending. They were known as the galacticos, and Beckham fit right in. Real Madrid, the most successful European club of all time and one of the richest, won absolutely nothing during Beckham's tenure—until this year. In the same period, Beckham won no international tournaments with the English national team. On top of not scoring goals, he does not win much. Did the L.A. Galaxy people read his resume at all?

The day he arrived in Madrid, the team shirt with Beckham's name on it sold out at the club store. It was obvious that the primary reason for Beckham's signing was Real's ambition to sell itself and Beckham as galactically renowned brands. Beckham was entirely unneeded as a player: He could not play in his right-wing position, which was beholden to Luis Figo, another exorbitantly paid galactico. Therefore, he frequently embarrassed himself playing in positions that required all the skills he never had: defense, tackling, using his left foot. His soccer career has steadily declined since 2003, and, when he started negotiating with the L.A. Galaxy, a place on Real's first team was beyond his reach. After the Galaxy deal's announcement, Real's couch, Fabio Capello, declared that Beckham would never play for him again. But, in the desperate race for the Spanish title, he reinstated Beckham, who actually briefly managed to contribute to Real's successful pursuit of the championship. The pressure of having to prove that he was one of the Real greats made him play like an occasionally good player, as he had been for most of his life.

Beckham arrives inthe United States with the dubious achievement of being the most overrated and overpaid player in the history of sports. The bright minds of U.S. soccer have apparently decided there is no longer a need to avoid the mistakes made by the ill-fated North American Soccer League (NASL). Back in the '70s, NASL spent all its money on aged, exhausted stars in the hopes of attracting the elusive American fan, who prefers sports with enough breaks to permit fetching another beer from the remote fridge. MLS has, in one fell swoop, destroyed its wage structure, creating a situation in which Beckham's teammates will earn up to 350 times less than he will—it is a matter of time before a player earning the soccer equivalent of minimum wage unleashes a vengeful two-footed tackle at Becks' delicate, precious legs (particularly since Beckham injured one of them in his last game for Real). With Beckham's landing on the American pitch, over will be the days when U.S. soccer was built from the ground up, when the primary fan base was immigrants familiar with the rules of the sport and capable of correctly pronouncing the players' names. Indeed over are the days of U.S. soccer.

Beckham's main quality in the U.S. market is, of course, his brand-name celebrity aura. If in doubt, witness the image of Becks as a fetching prince of a white house, saving his Sleeping Beauty as part of Disney World's "Year of a Million Dreams" advertising campaign. Thus Beckham has joined Donald Duck and Goofy in the U.S. soccer pantheon. Unlike the elitist circles of global soccer, where professional players are actually required to win games between their celebrity stunts, American sports-as-entertainment culture seems ready to worship unconditionally Beckham's right foot and boyish attractiveness. It also appears to be hungry for Mrs. Beckham's impressive vacuity—she once frankly owned up to never having read a book in her life—which should reach its height on U.S. television: Victoria has signed up with NBC for her own fashion reality special, in which David might be subjected to kinder, gentler hair-drying treatments.

The Beckhams' move to California should perhaps be of interest to a tired anthropologist studying the American penchant for turning moronic mediocrity into profitable celebrity—but never, ever to a soccer fan. For a true fan prefers watching the lesser celebrities who can use both of their feet, head the ball, and tackle; those players who score goals and do the unfashionable work of winning.