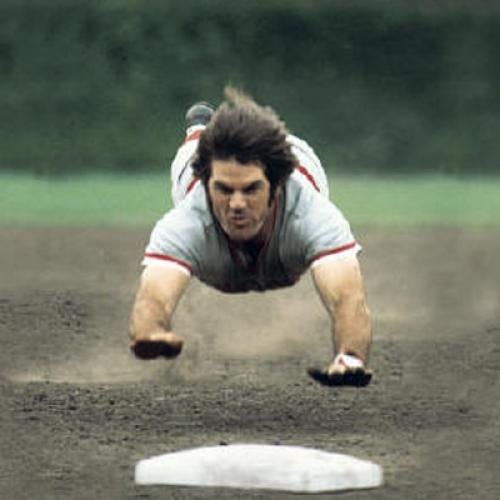

Why all the fuss about Pete Rose? Granted, his image has undergone a pretty grotesque metamorphosis: one day he's hugging his son at first base after breaking the most venerable record in baseball—Ty Cobb's 4,191 career hits—and the next day he's feverishly writing checks to low-life bookies. But the little-remembered truth is that Rose forfeited his hero status long before the commissioner's office started investigating his gambling habits. It happened in 1980, when he was playing for the Philadelphia Phillies, leading them to a world championship. State drug investigators discovered that a physician in Reading, Pennsylvania, had been prescribing large quantities of amphetamines to selected Phillies. Among them were Rose and several other notables, including Tim McCarver, who is now parlaying his hick accent, cornball humor, and clean-cut persona into a tenured position as one of America's most adored baseball broadcasters. During a period encompassing two seasons, 300 Dexamyl pills were prescribed in Rose's name—almost exactly one per game. If you infer that Rose was taking speed to "enhance performance," doesn't that take some luster off his world record? Actually, not necessarily. Uppers are so widely used in baseball that Rose could plausibly argue he had to take them in order to compete equally with Ty Cobb: otherwise he would have faced chemically assisted pitchers without any chemical assistance—something Cobb never had to do. Anyway, this is beside the point. What earned Rose a place in my hall of shame wasn't (allegedly) taking the uppers, but what he did afterward.

When the prescriptions came to light, Rose and other Phillies said they hadn't requested or received the drugs. Amazingly, state officials took the players at their word and concluded the prescriptions were phony: the doctor who wrote them—a longtime team physician for a Phillies farm club—must have been diverting the drugs to the black market or to personal use. The state attorney general even decided to prosecute the doctor (and the ardent Phillies fan who served as courier) for this diversion, never asking the obvious question: if you were a doctor trying to run a low-profile drug ring, would you write fake prescriptions out to Pete Rose, c/o Veterans Stadium? As the state's case gained momentum, Rose and his teammates faced a simple choice. Either testify that you used the drugs—which would have been legal, since they were prescribed by a physician, and which wouldn't have violated any written rule of professional baseball—or help send the doctor and courier off to the slammer muttering that they've been framed. And bear in mind: the two accused men were longtime friends of the Phillies organization. The courier, a middle-aged machinist, was virtually a team groupie. Long before any of the prescriptions had been written, he was picking up hoagies and Polish sausage from a favored sandwich shop in Reading and proudly delivering them to Phillies in the locker room, where he was warmly received. Well, that was then: this was now. Testifying under oath at a pretrial hearing, Rose and McCarver again claimed they had never asked for or gotten any speed. (As for Playboy interview in which Rose had admitted to taking amphetamines: he said under oath that he had been misquoted.) But then an obscure relief pitcher named Randy Lerch unexpectedly broke ranks. He testified that, yes, he had requested and received pills from the doctor. The judge dismissed the case, and the Phillies traded Lerch within a few weeks. The Philadelphia Inquirer's elaborate reconstruction of the affair, published in July 1981, left little doubt that the whole thing had been a cover-up involving not only the Phillies players, but the Phillies ownership and even state officials. Rose's success in dodging the bullet in 1980 may account for the tenacity with which he's now fighting all the evidence against him. And the incident may shed light on other things, too. Read this wistful tribute to Rose that appeared in Time a couple of weeks ago: "He was Charlie Hustle, the man who ran out even his bases on balls, who played with a boyish exuberance and devil-may-care abandon... He soared far beyond athletees who had vastly more natural grace." Sure did.

Speaking of guys who refuse to go down gracefully: Jeffrey MacDonald, the Green Beret convicted of murdering his wife and kids, is now the subject of a syndicated, BBC-produced documentary that questions whether he was proved guilty beyond a doubt. I haven't seen the show, but I nonetheless give you this guidance: don't waste your time: he's guilty. As far as I'm concerned, the clinching evidence has always been MacDonalds' claim that the murderers were drug-crazed hippies chanting, "Acid is groovy... Kill the Pigs." By 1970, when the murder occurred, no one who did drugs was still using the word "groovy" (this the possible exception of MacDonald, who had been taking amphetamines). In fact, if the list of suspects is confined to people still using that word at that late date, I know of only a couple who qualify: Jim Lang, host of the original "Dating Game," and Mike Douglas, who, as I recall, did more than one swinging rendition of the song "Feelin' Groovy." And then there's MacDonald. You decide.

I'm not trying to impress you, but: I recently had lunch with Dan Quayle. OK, it wasn't just me and Dan. It was me, Dan, about a dozen other journalists, and a couple of Quayle advisers who tended to look apprehensive when he was talking. The lunch was off the record, or on background, or something, but I don't think that prohibits me from sharing general impressions. It is true, as Quayle's defenders claim, that you come away from an encounter with him not overwhelmed by his lack of intelligence. But the reason isn't that he strikes you as bright: it's that the deficiency he exudes goes well beyond intelligence per se. He's just a generally out-of-his-depth guy: in lots of little ways, he's a couple of notches below what you'd expect from someone occupying his office (not to mention you-know-which office). He greets you with a rote, dishrag handshake and fuzzy eye contact reminiscent of Katharine Ross in The Stepford Wives. Then he sits down and fails to make passable small talk. He occasionally tells a dopey joke, and, when somebody tells a good one, he grasps it roughly two seconds after everyone else: once he even echoed the punch line in less subtle terms, as if anyone but him needed to have it boiled down. Quayle does demonstrate a mastery of fact in some areas (like weapons in space, for example, and weapons in space), and he's obviously working to expand his expertise. But he can't seem to put facts together with sustained coherence. Notwithstanding all this, and maybe partly because of it, he's a likable guy—straightforward, and even possessing shreds of self-awareness. In fact, I left the lunch feeling sorry for him: here's someone who, through a series of events largely beyond his control, has been conspicuously elevated beyond his level of competence. I vowed not to write anything nasty about him for a while. But then I remembered: whatever he lacks in competence is being manufactured for him: he's surrounded by very bright aides, who gravitate toward power like moths to light, however dim the bulb. He'll get by. Those jokey "Quayle '96'" T-shirts circulating in Washington this summer already made me a little queasy.

Robert Wright is a Senior Fellow at the New America Foundation. He is the author of, most recently, The Evolution of God (Back Bay Books).