In the spring of 1995, Jim Clark, who had spent half his life spying on others, was sure someone was spying on him. He first noticed the person when he got off the plane in Germany. Now, at the train station in Bonn, he could see the man’s reflection in the ticket counter window. He knew from experience that people do silly things when they think they’re being watched, but he did them despite himself: zigzagging across the terminal, spinning around, even walking backward.

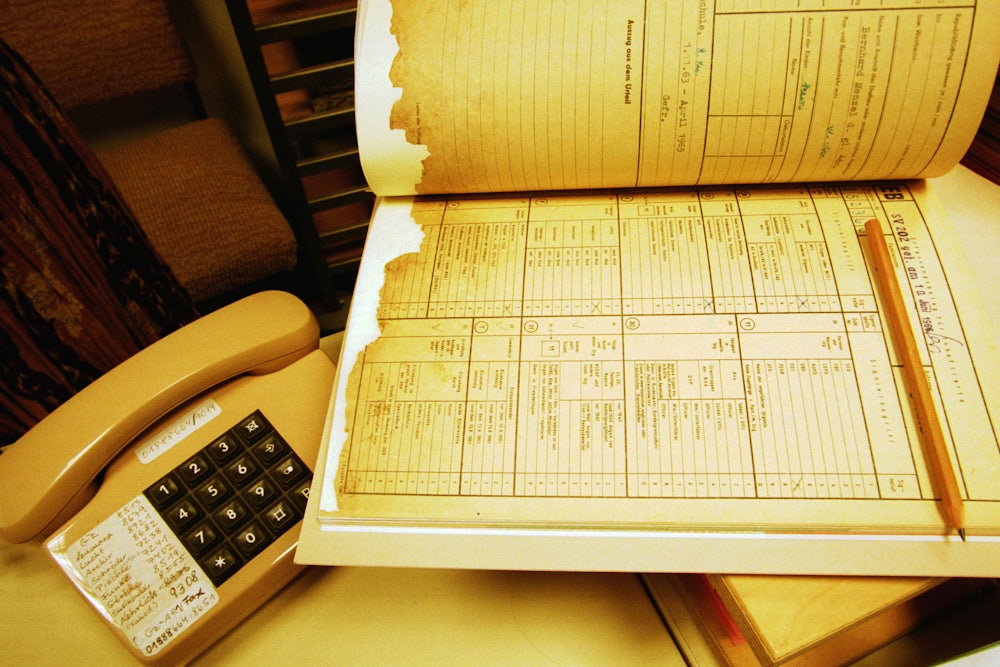

He made his way back to America, but, when he entered his apartment in Virginia, he was certain the FBI had been there before him. His clothes were out of order, and his computer had been turned on. “Gonna say you’re a ... spy,” he mumbled to himself, anticipating the FBI’s accusations. “You work for the KGB!” He’d already dug a hole in the woods out back and buried one of his miniature cameras, but there was still other evidence of his nearly two decades as a secret agent for the East Germans: dolls with slits in the back for film and a hollowed-out Reader’s Digest condensed book for concealing documents. “An easy [mark]. An easy mark I am!” he said.

With each day, his paranoia increased. At night, alone in his apartment, he talked to himself, even though he knew the FBI might be listening. “I’ve gone through this conversation many times,” he declared to no one in particular. “I’ll answer your question under one condition: That no further questions will occur.” He paused and looked around the empty room. “James Clark. Your honor ... not guilty.” He tried to reach his East German contact, a man he knew only as “Harry.” But it was too late. “FBI!” he yelled to himself. “You’re under arrest!”

And then he was. On October 4, 1997, the FBI arrested the 49-year-old paralegal and private investigator for espionage. The government also arrested Jim’s longtime friends—Kurt Stand and his wife, Terry Squillacote—as co-conspirators in what is likely to be the last spy case of its kind. All three were devoted Marxist-Leninists who came of age during the 1960s and, according to wiretaps and court testimony, spied for the East Germans from the 1970s until 1990. Even stranger, all three refused to give up on communism long after the Berlin Wall crumbled. As late as 1997, Kurt and Terry formed a Marxist study group, which convened once a month at their suburban home, and tried to organize a new espionage ring with a band of South African Communists. Their goal, Terry wrote in the discussion group’s syllabus, is “Socialist transformation.”

At their trial last October in Alexandria, Virginia, reporters and strangers crowded into the courtroom to see what they looked like, while old leftists seized upon the case to relive the wars of their past. At least a half- dozen Socialists, Communists, and assorted “progressives” sat behind the defendants each day, wearing red roses and warning of a new McCarthyism; one even refused to stand when the judge entered the courtroom. The FBI is “trying to refight the old ideological wars of the 1950s,” warned Robert Meeropol, the son of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Conservative David Horowitz, meanwhile, claimed there were dozens more just like them lurking in suburbia. “Why only three?” he asked in Salon magazine after their arrests.

But the story of these spies—pieced together from FBI wiretaps and the first public interviews with Kurt and Terry—turns out to be less a tale of seasoned agents than of three minds consumed by an archaic religion. Unable to let go of their ideology, they became increasingly irrational until, by the end, they were no longer revolutionaries but alchemists of revolution, trying to create a new order out of nothing—a handful of minor documents and their own writings on bourgeois materialism.

When Kurt and Terry moved to Washington, D.C., in 1980, there was nothing especially unusual about them. They lived in a part of the city that was neither too fancy nor run-down—middle class for the true middle class, they liked to say. Terry studied law and, in 1991, went to work in the Pentagon’s Office of Acquisition Reform, where she received outstanding evaluations and even a reinventing government award from Vice President Al Gore. Kurt, after wandering from job to job, first as a longshoreman and then as a maintenance man, finally settled in as an official with a food workers’ union. They were, of course, old lefties, shopping at the co-op and boycotting Nestle. But, with their two kids and minivan, they seemed almost, well, bourgeois. Their son, Karl, had severe learning disabilities, and Terry spent most of her time fighting with the school bureaucracy to ensure that he got a good education. She once wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post on his struggles, which she clipped and kept with Kurt’s old college essays on imperialism. Neither of them could ever throw anything out, and the house resembled an antiques bazaar, with jars of Italian marbles, used books, and magazines from the ‘70s strewn everywhere. In winter, they’d host a New Year’s party for their friends--a happy occasion where Terry’s pals from the establishment mingled with Kurt’s associates from the Democratic Socialists of America.

One person who sometimes attended was a paralegal with the U.S. Army named James Clark. Short and bookish, with receding gray hair and thick glasses, he was the only one in the room more reserved than Kurt: he avoided office birthday parties and, if he had anything personal to say, wrote it down in his diary, which he’d kept since he was a teenager. “No one had a bad word to say about the guy,” says John Murphy, a former FBI agent and U.S. Marine who hired him as a private investigator in 1996.

But, every so often, unbeknownst to their friends and neighbors, Jim, Kurt, and Terry all allegedly received secret instructions from Harry, their East German contact. “I am sure you will get what we want,” he wrote Terry in one message. While the kids were out playing, Terry would sometimes go down into the basement and listen to Morse code until her head pounded. Kurt, for his part, would mostly write long analyses of the labor movement and send them overseas. He thought of himself not so much as a traitor but as a friend, a collector of information. In Berlin, Harry kept careful track of all of their exchanges. “Everything arrived intact,” he’d write. Or: “We do like [the] photos.”

Although they never appeared to secure any damaging material, Jim chronicled almost everything he saw: newspaper clippings, college syllabi, medical reports. “He was like a ferret,” said one FBI agent. He even coaxed from his friends in the State Department a dozen or so classified documents, including one marked “top secret,” which he couldn’t understand but that satisfied Harry the most. So diligent was Jim that one day the Stasi invited him to Berlin and presented him with a medal, which it took back afterward so that there’d be no evidence. As the century came to a close, Harry suggested in the East German files that everything was going well. But it was one of the last times he would have an assignment for them.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1990, so, too, did all three defendants. One day in despair, Jim took a hammer and smashed one of his miniature spy cameras. He then walked out to the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge and scattered the bits in the Potomac River. A few miles away, Terry was even more distraught. According to friends, when the Soviets lowered the red flag over the Kremlin for the last time in 1991, she could barely get out of bed. She stayed home and watched CNN and cried for hours while her colleagues at the Pentagon celebrated the end of the Evil Empire.

More and more, Terry retreated into her black moods. She took antidepressants and saw a shrink. History had not, as she’d expected, delivered them. It had screwed them. She had spent years trying to get a position at the Pentagon that would please Harry, who had gradually become her lover; now that she finally had such a job, he’d abandoned her in the bowels of the Defense Department. “You know, I definitely need to open up my life and get more sense of gratification in it, because walking into that concrete bunker is killing me,” she told her brother. “It’s just killing me.”

Then, one day in 1995, her husband gave her a book called Armed and Dangerous, by Ronnie Kasrils, hoping it would cheer her up. On the cover, Kasrils, the former head of military intelligence for the African National Congress, wore a t-shirt emblazoned with a hammer and sickle. Like Terry, he had been trained in East Germany, and the book read like a spy thriller. But, unlike her, he had helped transform his country and now served openly in the government. “As for what I have done,” Kasrils proclaimed, “I consider it something lofty and noble.” Terry read each page, then read them again. Afterward, she tried for days to organize her thoughts in a letter to the author: “First let me send congratulations to you, and to those with whom you work, from myself and others here who also believe in the struggle to produce a better world.” So much had happened since 1989, since the fall of communism, she didn’t know where to begin. “Subjectivism, rule of law, assertion of objective forces of history....” she continued. “[W]hat do these things mean about how we achieve revolutionary change in society?” She typed and typed until she had written more than five single-spaced pages. She wondered if he’d read between the lines, if he’d see what she really wanted ... needed. “It would be so nice to sit together,” she wrote, “and have a glass of that brandy you enjoy so much.”

She signed the letter “Lisa Martin,” then drove to Riverdale, Maryland, where a few months earlier she’d opened a post office box under a fake name, and sent it off. Kurt told her not to expect anything, but she kept hoping anyway. She railed endlessly about the imperialists in the Pentagon and at Harry, who helped put her there. Finally, just as her post office box was about to expire, she opened it up and found an envelope. She tore it open and began to read:

Dear Lisa ... I have taken the liberty of asking one of our special components to make itself available to you in the States.... Should you wish to set out on this trek, I ask that on October 12th, you travel alone to New York. At 7:00 p.m. my representative will be in the Plaza Hotel in The Oak Bar. Please carry a copy of Armed and Dangerous and have with you this letter.... Yours truly, Ronnie Kasrils

There were, of course, some suspicious things to be found in all of their pasts, things that most people had long since forgotten. “I declare the end of my cooperation with the Selective Service System,” Jim wrote in college in 1967. “That agency serves as the murderous tool of Washington’s greedy corporate capitalist regime in its brutal attempts to suppress the struggling masses of the world.” The ordinarily quiet Jim then burned his draft card. A photographer from Time happened to capture him in the act—a skinny, red-headed teenager holding a match.

A campus Bedouin, Jim drifted from university to university until, in 1973 at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, he met a young hippie named Kurt Stand, a red diaper baby whose parents had fled Germany during World War II. On campus, Kurt was already a quiet hero, an amalgam of the Old and New Left. Tall and thin, with long sideburns and bone-white skin, he worked on the docks to pay for school and tried to organize the campus workers. “He knew all the Marxist literature inside out,” says one of his old university professors, Jack Zipes. “It was remarkable what he had read at that age.”

Indeed, unlike most of his generation, Kurt was not so much rebelling from his past as succumbing to it. The FBI had pursued his parents during the McCarthy era, and Kurt had grown up in a shadowy Communist underground in New York. His parents used to periodically bring Kurt to Germany, where they had known Harry for years. And, according to East German files presented in court, Harry recruited Kurt as an “agent in the West” when Kurt was only 19--allegedly with his parents’ blessing. Kurt and his parents both deny this, and the FBI could never prove it. But his code name was “Junior,” and Terry later wrote in a letter to the judge: “It was really mostly his parents’ bag, and primarily the father’s.”

Whatever the case, before long, Jim was crashing at Kurt’s apartment near Pulaski Street, Milwaukee’s version of Haight-Ashbury. At night, the two comrades attended seminars on “black liberation” and “imperialism” at the youth arm of the Communist Party. While more and more students drifted away from their politics, one person drawn to them was a young dilettante from down the street named Terry Squillacote. Talkative and high-strung, with thick, curly, black hair and a limp caused by a birth defect, she was the antithesis of Jim and Kurt: ambitious, nervous, upper middle class. She had graduated high school in only three years and was at the top of her class at Wisconsin.

But one day she walked out of her Marxist philosophy class and saw Kurt standing there. “It was like he had a light over his head,” she would recall years later. When the two of them started dating, Kurt’s friends were horrified. “They thought Terry was some kind of petty bourgeois dilettante with a big mouth,” says Marty Horning, who went to school with both of them. After their engagement, “there was even a plot to sneak him out of town. It included the guy who was going to be the best man at his wedding. So, when the wedding did take place, there was a whole group of people who weren’t there.” But Kurt saw something in Terry he couldn’t fully explain. Maybe it was the way she couldn’t stop talking or dissolved his shyness late at night. And one day he did something he had apparently done only once before with Jim: he introduced her to his Uncle Harry.

According to all accounts, Harry was a natural seducer. He was tall with wavy hair. He grew up on the Baltic coast and always talked about the sea. He taught Terry how to listen to Morse code and read Spanish numbers. He invited her and Kurt and Jim to safe houses around the world and sent them long coded messages in broken English. In 1990, after Terry had gotten a job on the House Armed Services Committee, he lauded her efforts in a secret missive: “It was very clever and courageous how you got the internship at yur oncle’s [sic] office. Thank you for the details of the hearings (it was your first intern[al] political information. Congratulation!).”

Terry, perhaps more than any of them, coveted such attention. “I never loved anyone like I did Harry,” she told her friends after her arrest. More than anything, she liked to feel pretty. Born without her right leg from the knee down and with a club left foot and hand, she spent much of her childhood in hospitals, learning to walk with a prosthetic limb. When she went to meet the South African agent in New York, she wanted to wear a miniskirt so he could see her injuries and understand why she was so dedicated to helping the less fortunate.

But, with Harry, it was different from the start. Her handicap seemed to be part of her beauty. Once, according to family and friends, when she was pregnant with her daughter, Rosa, she went swimming in a pool with Harry in Europe. As she lay on her back in a black bathing suit, the sun illuminating her figure, he told her she reminded him of the swan in Menotti’s opera: “O black swan, where, oh, where has my lover gone?... Oh, take me down with you. Take me down to my wand’ring lover with my child unborn.”

When the CIA went through the East German files after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it discovered an American agent with the code name ... Schwan.

More than a decade later, when Terry left the post office box with the South African’s letter, she kept thinking: “I did it! I did it. All those years! All those years, and I did it, I did it!” At home she called Kurt, who was away on business. “Come home,” she said. “I need to show you something.”

“What is it?” he asked nervously.

She read him the letter. “Jesus Christ Almighty,” he said. He told her he’d cancel his trip to New York. “Jesus Christ,” he said again.

“Hurry,” she said.

At last, on October 12, 1996, she packed up her few things and drove to New York. It was windy and dark when she arrived at the hotel, holding her copy of Armed and Dangerous in her hand. The bar was on the first floor, and she walked down a long marble corridor adorned with elaborate gold trim, a chandelier, and an old wooden humidor. As Terry looked around the room, an elderly man with dark hair, pale, pocked skin, and glasses approached her. “That’s a very interesting book,” he said.

He introduced himself as Robert; she as Lisa. “Do you mind if I have a cigarette?” she asked nervously.

They sat by a giant window overlooking Central Park and, for a while, talked circuitously, cautiously, each trying to make sure the other was not a crank or a double agent. His parents, he said, were born in South Africa; they fled after the nationalists came to power. “I consider myself a citizen in absentia,” he said.

“You should understand that this is not a tabula rasa for me,” she said, sipping her vodka tonic. “I’m coming with a history.” Unfortunately, she went on, things never came to fruition. “I always felt more like someone who was in training for a long time.”

As they listened to the jazz piano in the main dining room, not far from where the Vanderbilts and Goulds used to discuss the stock market, they ate foie gras and talked about the movement. “I believe in the struggle for socialism,” she said, happy to be with someone who understood. She wanted to continue what Kurt’s family had started back in 1918. “I want them to know that their life wasn’t useless,” she said.

Terry warned Robert that she might be too high a risk for him, no matter what she did—Harry had told her that the Germans were searching for three people in D.C., two men and one woman, who had spied for the Stasi. Robert, though, didn’t flinch. He told her to get rid of her post office box and gave her a book of Nadine Gordimer’s short stories. Inside was $1,000 for expenses.

There are no simple explanations for why people betray their countries. A traitor is different than an adulterer or murderer, for he betrays not just one person but everyone, a society, a culture, a way of life. Even the people whom he tries to help often look upon him with scorn: the English, for instance, jeered Benedict Arnold until the day he died.

Tod Hoffman, a former spymaster, wrote that spies would offer a potential recruit anything: “affection, protection, dignity, material gain, or whatever else they are most in need of.” Historically, most traitors were driven, at least in part, by money. Judas demanded 30 pieces of silver from the chief priests, while Benedict Arnold asked the British crown for today’s equivalent of $5 million.

But, in the case of Terry, Kurt, and Jim, money seems to have been superfluous. Instead, they seemed to have been driven by something else, something more disturbing. “Today—more than ever—it is hard to accept that anyone engages in grand gestures for the sake of ideology...,” Hoffman explains. “Experienced intelligence ... would much prefer to deal with someone seeking to settle a personal score or demanding cash payment. Such people are more predictable.”

Indeed, one day after Terry got back from New York and was all alone in her office, she showed how unpredictable she could be. Everyone had gone to lunch, except for a secretary. She looked around, her heart pounding. In the safe were several secret documents on U.S. defense spending. She had to do it now—before anyone came back—but her camera was at home, inoperable from disuse. Unsure what to do, she took one document to the Xerox machine, even though Harry had always warned her not to copy anything. The bright light on the Xerox machine flashed slowly ... across ... the ... screen, and she lifted up the cover, and put down another page, then another. Outside, in the corridor, security officers walked by, their heels clicking on the linoleum floor. As her colleagues returned from lunch, she dropped the documents on her desk, then later picked them up and hurried through the catacomb of corridors until she was breathing in the night air.

At home, she cut off all the classified markings, just as Harry had taught her, then set them on fire. “I got to bed, and the house still reeked of smoke,” she told Kurt, who had brought her a bottle of Wite-Out to help clean up the markings.

That week she and Kurt worried about how to transport the documents to New York. What about putting them in wrapping paper, like a gift? Terry asked. “I’d kind of like to dress it up a little bit.”

Kurt recommended buying a briefcase at Kmart, something cheap. “That’s what I would do,” he said.

Finally, Terry decided just to stick them in her brown satchel. As planned, she waited for Robert outside the Museum of Modern Art.

“Happy New Year!” she said.

On the sidewalk, in the cold, vendors were selling books and prints. “Happy New Year,” Robert said.

They went inside and looked at Cezanne and Seurat. But even there she was jittery. “I have something for you,” she said. “It’s in the trunk.”

After they fetched the bag from the car, they went into an Italian cafe on Fifth Avenue. When the waiter was out of earshot, Terry told her new handler what she had done. “I happened to have a day in the office when everyone was out, just me and the secretary”—even now she couldn’t believe it—”so I figured I might as well try to score what I could.”

She told Robert about the Xerox machine. “In the old days I would have filmed all that ... [but] this is actually the first time that I’ve ever....” Her voice trailed off. Robert offered to get her a new camera and a fake passport. Then he handed her another book. As they stood to go, he picked up the satchel.

A few months later, Terry and Kurt packed up their car and headed for Alabama with the two children for an Easter holiday with relatives. After driving through the night, with the windows open and the radio blaring, they stopped in Atlanta. While Kurt and the kids rested at the hotel, Terry drove across town to another prearranged meeting with Robert. “I didn’t realize ... exactly what was in the bag” last time, he said excitedly, as they sat down. “Everybody’s doing cartwheels.”

There was only one small problem. He pulled out a German article about ex-Stasi agents who it appeared were being investigated by the new unified German government for espionage. Terry studied one of the photos more closely. That looks like Harry! she blurted out.

She became agitated, and Robert tried to comfort her. They’d already drawn up a list of all the people who could betray them, including Terry’s in-laws and brother. “Certainly not my brother,” Terry had written on a piece of paper.

What about Harry? Robert asked. He would never betray her; he loved her. And Jim Clark? She didn’t think so, though she couldn’t be sure. And Kurt? “He’s totally on board,” she said now. “He’s thrilled to death.”

Indeed, later that night, despite their fears, Kurt and Terry rode the glass elevator up to the seventy-second floor of the Westin Peachtree Plaza Hotel to complete their fake passports for a clandestine trip to South Africa. There was no place to leave the kids, so they had reluctantly brought them along—and pretended it was a business meeting with one of Kurt’s clients. But 13-year-old Rosa already had an inkling of what was going on. “Did Mom tell you the good news?” she’d earlier asked Kurt.

“Which good news?” Kurt had replied, somewhat startled.

“The Lisa good news,” she’d said, referring to Terry’s South African code name.

Now the whole Squillacote and Stand family sat down at a table with Robert, the secret agent. The Sun Dial Lounge revolved slowly, and they could see, in the distance, the CNN Center and the Georgia Dome. While the kids sipped their Shirley Temples and Huck Finns, Robert brandished several three-by-five cards. Terry signed her name “Patricia A. Cunningham,” and Kurt signed his “Harold T. Harding.” Finally, when everything was in order, they looked out the window and watched the world spin beneath them.

It was around this time that someone slipped a note under Jim Clark’s door. He’d been out after work and almost stepped on it when he came home. Scribbled in almost illegible black ink, it told him to be at the Best Western hotel at 20:00 hours and wear a baseball cap. It was signed, “Keep the faith, Your Friend.”

Uncertain what to do, he drove past the hotel, then came home before anyone could see him. As he entered the apartment, the phone rang. He picked it up, and a man with a Russian accent told him to meet at the lobby of the hotel. It’s about Harry, he said, then hung up.

Terrified, Jim climbed back in his car and returned to the Best Western for the second time that evening. It was just before midnight when he walked into the lobby, his hat pushed down over his forehead. “You don’t have to wear the cap now,” a man said, standing in the center of the room. Jim removed his cap and the man led him up to his room.

“Sit down,” he said, pointing to the bed. “I have a greeting from Harry.... My people in Moscow work with him. I’m from Russian Embassy.”

Jim didn’t say anything. Maybe the room was bugged.

“One of my people was supposed to make contact with you,” he continued. “You remember that?”

Jim had tried through Harry to establish contact with the KGB a few years before. “No,” he said, lying just in case.

“Harry,” the man went on, “had a little trouble with authorities in Germany.”

Jim turned white. The man said Harry was fine, but they suspected that someone in their unit was fingering them one by one. Then he dropped the bombshell: the couple, his friends, may no longer be reliable. He insisted that they were safe as long as nobody did anything dumb. “But if somebody starts to ... how you say? Blabber the mouth or something.” His voice trailed off, as if to let the prospect sink in.

“No one else knows,” Jim assured him.

The man took out a bottle of scotch and offered Jim a drink. “You understand that the trust thing is still just partial with me,” Jim said, raising his glass.

Of course, the man said, and they both clinked glasses and poured down their scotch.

Over the next few nights, they met secretly. But, just as Jim was starting to feel more secure, Terry called. She had seen another article, this one suggesting that Harry had been arrested. As the two of them huddled together at a crowded pub on Twelfth Street—Kurt was away on business--Jim finally told her about the Russian. After a while, they both became convinced he was an undercover FBI agent. How else did he know so much? Terry lit a cigarette and let the smoke curl around her mouth. Jim had just “slit” all of their throats.

She raced home and called Kurt, then typed a letter to her South African handler, warning him that they had all been substantially compromised. “I would like to try to find a way to get out and live a productive life elsewhere,” she wrote, “where I could continue to make a contribution.” In a separate missive, she said she no longer trusted Jim. He seems to think “Ross Perot is a progressive direction for activists.”

Jim, meanwhile, no longer trusted anyone. He made a copy of the federal statute against espionage and studied it for hours. “You’re so fucked,” he told himself.

When Kurt returned, he tried to calm them both down. “[T]hey’re throwing this out to see if anybody pops up,” he said. “And then they can ... catch them.”

But, a few days later, a woman with a German accent called Terry and said: “This is your friend’s daughter. I have message from my father.... Can I read it to you?”

Yes, Terry said, her heart racing. “Your friend is in trouble. He is being closely watched.”

The woman asked if Terry understood, then the line went dead.

Now they all began to panic. “I gotta get outta here,” Jim said. At his apartment he ripped apart his books and journals, shredding any evidence. “Vernichten,” he said in German. “Destroy! Destroy!” He stuffed his belongings in plastic bags and dragged them across the floor. “I’m going far away—Tibet!”

But, before he could even get downstairs, the Russian called and left a message on his machine saying they had to meet. “Get lost!” Jim screamed at the machine. “I don’t wanna fuckin’ see you again!” He took out his passport and stash of money. He knew a place in Mexico, an abandoned building near the border where he could hide. But, instead of leaving, he started to sob. “I’m not very good at this,” he said. He opened the window and stuck out his head. “My God,” he muttered, “my parents.”

He bent over and started to hyperventilate. Don’t lose control, he told himself. Don’t lose control. “I know nothing,” he shouted. “I know nothing.”

On his way outside, a dozen FBI agents surrounded him. A few hours later, Terry and Kurt tried to make it to a hotel in Virginia to meet with Robert. But, as they exited the elevator, a second team of FBI agents enveloped them. In the ensuing chaos, Terry noticed Robert standing with the other agents, and it suddenly dawned on her: he was FBI, just like the Russian and the German woman who had called claiming to be Harry’s daughter.

The spy lives in his own moral universe. He lives in a place where there is little light or intimacy, where, as John Le Carre once wrote, people “have seen too much and suppressed too much and compromised too much and in the end tasted too little.” Ultimately, he can trust no one—for, deep down, he knows that a person who can betray his country can betray anything or anyone. “The difference between intelligence officers and other people,” explains the spymaster Hoffman, “is that we anticipate—and, over time, expect—lies and faithlessness. Every relationship carries a stain of suspicion.”

At the trial, it became clear the degree to which every character had betrayed someone for something. Robert, the undercover FBI agent, had betrayed Terry for his country. Terry had betrayed her country and husband for Harry. Harry, who went to jail briefly in Germany and was now a real estate agent in Berlin, had betrayed Kurt for Terry. (Kurt learned about his wife’s infidelity for the first time in the newspaper after their arrest.)

Meanwhile, Kurt’s lawyer, Richard Sauber, left open the possibility that Kurt might turn against his wife to exculpate himself. “A man in Mr. Stand’s position ... has a terrible Hobson’s choice,” Sauber told the judge. “If he testifies to his own minor role ... he places himself in the impossible position of pointing the finger at his spouse.” Though in the end Kurt could not betray the only woman he had ever loved, there was still one last act of betrayal: in exchange for a shorter sentence, Jim pled guilty and testified against Kurt and Terry. Afterward, when the prosecution asked Jim if he still considered Kurt and Terry his friends, he looked at them plaintively and said, “Yes.”

The trial lasted nearly a month. Kurt and Terry were charged with conspiracy to commit espionage, attempted espionage, and illegally obtaining national defense information. Two of the city’s best defense attorneys took the case almost entirely pro bono because they believed their clients had been entrapped. Terry’s lawyer, Larry Robbins, and Sauber revealed how the FBI had found their clients’ names in the Stasi files, then tapped their phones for more than a year, found Terry’s letter to the South Africans in a search of her home, and set up an elaborate sting with Robert and the Russian undercover agent. They argued that, unlike Jim, their clients had never turned over any classified documents until after the sting. And, as the spectators stared in bewilderment and Terry sank in her chair, they noticed that even the information passed on during the sting had already largely appeared in The New York Times and Jane’s Defense Weekly.

Oddly, the prosecution mostly shied away from the defendants’ archaic ideology. It emphasized money as their primary motive, even though they had received relatively little. Venality, it seemed, was easier for the jury to judge than idolatry.

The defense, in turn, chose the only explanation that seemed plausible for Terry’s strange behavior during the sting: she must be nuts. The defense cited the FBI’s own internal psychiatric report, which the agency used in designing its undercover operation and which stated that Terry suffered from “cramps and depression”—and would likely try to kill herself after being caught. But, when the jury looked at all three defendants, it saw only one thing: Benedict Arnold.

Jim was sentenced to twelve years in prison. Kurt and Terry received 17 and 21 years, respectively. In a note to the judge, Jim wrote that he had spied “entirely for ideological reasons.... I have always been dedicated to a political movement that is opposed to greed and selfishness.” In a separate letter, Kurt maintained his innocence. Terry, meanwhile, pleaded futilely for mercy. “This is the last gasp of the Old Left,” said one of their friends in the Old Left as they departed the courtroom.

When I finally met Terry and Kurt, they were waiting to be transferred from the local Alexandria jail to a federal prison. Kurt came down to a visitors’ room. He sat behind a Plexiglas window and talked through a phone. He had lost weight, and his uniform hung too loosely over his shoulders. His kids had gone to live with his brother in the Bronx, and he barely saw them. “They have a right to be upset and angry” with us, he said. “They have a right to have Mother and Father home with them.”

When I went downstairs to see Terry, she had just been moved to the psychiatric floor. Her face was puffy, and her hair stood almost on end. After only a few minutes, a guard handed her two pills and a glass of water. “Time’s up,” he said. Before she left, I asked her the only thing I still didn’t know: Had she lost faith in her beliefs? She looked at me oddly and pushed her face close to the glass so that I could see her veins. “No,” she said. Just the opposite. In jail, she said, she had finally found a place where the state “took care of all the broken people of the world.”