The future relations between the Liberal party and the Labor party have been the subject of very lively discussion in England during the past few weeks—brought to a head by the defection of Sir Alfred Mond to the Conservative side. So far, however, as the leaders are concerned on either side, we are not yet much enlightened. Mr. Lloyd George has let it be known that, on terms, he would not decline a working arrangement between the two parties; and Mr. Snowden that he, also on terms, would welcome it. But Lord Oxford—perhaps wisely—has avoided the issue for the present by merely observing that no conversation have occurred as yet; and Mr. Ramsay Macdonald is also uncommitted. Perhaps it may interest readers of the New Republic to hear a little of the reactions to the present situation in British politics of one who reckons himself a Liberal of the extreme left.

I do not wish to live under a Conservative government for the next twenty years. I believe that the progressive forces of Great Britain are hopelessly divided between the Liberal party and the Labor party. I do not believe that the Liberal party will win one-third of the seats in the House of Commons in any probable or foreseeable circumstances. Unless in course of time the mistakes of the Conservative government produce an economic catastrophe—which is not impossible—I do not believe that the Labor party will win one-third of the seats in the House of Commons. Yet it is not desirable that the Labor party should depend for their chances of office on the occurrence of national misfortune; for this will only strengthen the influence of the party of catastrophe which is already an important element in their ranks. As things are now, we have nothing to look forward to except a continuance of Conservative governments, not merely until they have made mistakes in the tolerable degree which would have caused a swing of the pendulum in former days, but until their mistakes have mounted up to the height of a disaster. I do not like this choice of alternatives.

The conventional retort by Labor orators is to call upon Liberals to close down their own part and to come over. Now it is evident that the virtual extinction of the Liberal party is a practical possibility to be reckoned with. A time may come when anyone in active politics will have only two choices before him and not three. But I believe that it would be bad politics and bad behavior to promote this end; and that it is good politics and good behavior to resist it.

Good politics to resist it, because the progressive cause in the constituencies would be weakened, and not strengthened, by the disappearance of the Liberal party. There are many sections of the country, and many classes of voters, which for many years to come will never vote Labor in numbers or with enthusiasm sufficient for victory; but which will readily vote Liberal as soon as the weather changes. Labor leaders who deny this are not looking at the fact of politics with unclouded eyes.

Good behavior to resist it, because most present-day active Liberals, whilst ready on occasion to vote Labor and to act with Labor, would not feel comfortable or sincere or in place as full members of the Labor party. Take my own case. I am sure that I am less conservative in my inclinations than the average Labor voter; I fancy that I have played in my mind with the possibilities of greater social changes than come within the present philosophies of, let us say, Mr. Sidney Webb, Mr. Thomas, or Mr. Wheatley. The Republic of my imagination lies on the extreme left of celestial space. Yet—all the same—I feel that my true home, so long as they offer a roof and a floor, is still with the Liberals.

Why, though fallen upon such evil days, does the tradition of Liberalism hold so much attraction? The British Labor party contains three elements. There are the Trade-Unionists, once the oppressed, now the tyrants, whose selfish and sectional pretensions need to be bravely opposed. There are the advocates of the methods of violence and sudden change, by an abuse of language called Communists, who are committed by their creed to produce evil that good may come, and, since they dare not concoct disaster openly, are forced to play with plot and subterfuge. There are the Socialists who believe that the economic foundations of modern society are evil, yet might be good.

The company and conversations of this third element, whom I have called Socialists, many Liberals today would not find uncongenial. But we cannot march with them until we know along what path, and toward what goal, they mean to move. I do not believe that their historic creed of State Socialism, and its newer gloss of Guild Socialism, now interest them much more than they interest us. These doctrines no longer inspire anyone. Constructive thinkers in the Labor party, and constructive thinkers in the Liberal party, are trying to replace them with something better and more serviceable. The notions on both sides are a bit foggy as yet, but there is much sympathy between them, and a similar tendency of ideas. I believe that the two sections will become more and more friends and colleagues in construction as time goes on. But the progressive Liberal has this great advantage. He can work out his polices without having to do lip-service to Trade-Unionist tyrannies, to the beauties of the class war, or to doctrinaire State Socialism—in none of which he believes.

In the realm of practical politics two things must happen—both of which are likely. There must be one more general election to disillusion Labor optimists as to the measure of their political strength standing by themselves. But equally on the Liberal side there must be a certain change. The Liberal party is divided between those who, if the choice be forced upon them, would vote Conservative, and those who, in the same circumstances, would vote Labor. Historically, and on grounds of past service, each section has an equal claim to call itself Liberal. Nevertheless, I think that it would be for the health of the party if all those believe, with Mr. Winston Churchill and Sir Alfred Mond, that the coming political struggle is best described as Capitalism versus Socialism, and, thinking in these terms, mean to die in the last ditch for Capitalism, were to leave us. The brains and character of the Conservative party have always been recruited from Liberals, and we must not grudge them the excellent material with which, in accordance with our historical mission, we are now preserving them from intellectual starvation. It is much better that the Conservative party should be run by honest and intelligent ex-Liberals, who have grown too old and tough for us, than by Die-hards. Possibly the Liberal party cannot serve the state better than by supplying Conservative governments with Cabinets, and Labor governments with ideas.

At any rate, I sympathize with Labor in rejecting the idea of cooperation with a party which included, until the other day, Mr. Churchill and Sir Alfred Mond, and still contains several of the same kidney. But this difficulty is rapidly solving itself. When it is solved, the relations between Liberalism and Labor, at Westminster and in the constituencies, will, without any compacts, bargains or formalities, become much more nearly what some of us would like them to be.

It is right and proper that the Conservative party should be recruited from the Liberals of the previous generation. But there is no place in the world for a Liberal party which is merely the home of out-of-date or watery Labor men. The Liberal party should not be less progressive than Labor, not less open to new ideas, not behindhand in constructing the new world. I do not believe that Liberalism will ever again be a great party machine in the way in which Conservatism and Labor are great party machines. But it may play, nevertheless, the predominant part in molding the future. Great changes will not be carried out except with the active aid of Labor. But they will not be sound or enduring unless they have first satisfied the criticism and precaution of Liberals. A certain coolness of temper, such as Lord Oxford has, seems to me at the same time peculiarly Liberal in flavor, and also a much nobler and more desirable and more valuable political possession and endowment than sentimental ardors.

The political problem of mankind is to combine three things: economic efficiency, social justice, and individual liberty. The first needs criticism, precaution and technical knowledge; the second, an unselfish and enthusiastic spirit, which loves the ordinary man; the third, tolerance, breadth, appreciation of the excellencies of variety and independence, which prefers above everything to give unhindered opportunity to the exceptional and to the aspiring. The second ingredient is the best possession of the great party of the proletariat. But the first and third require the qualities of the party which, by its traditions and ancient sympathies, has been the home of economic individualism and social liberty.

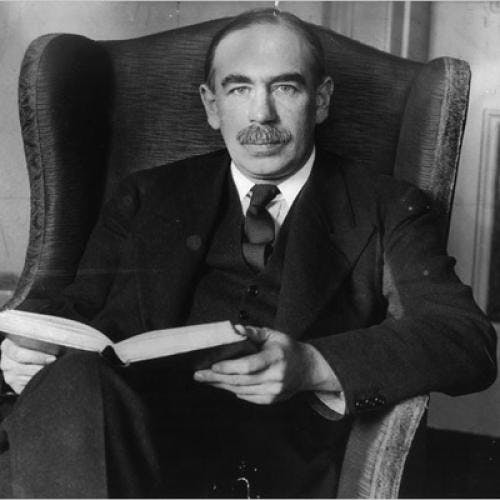

John Maynard Keynes was a British economist whose books include The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.