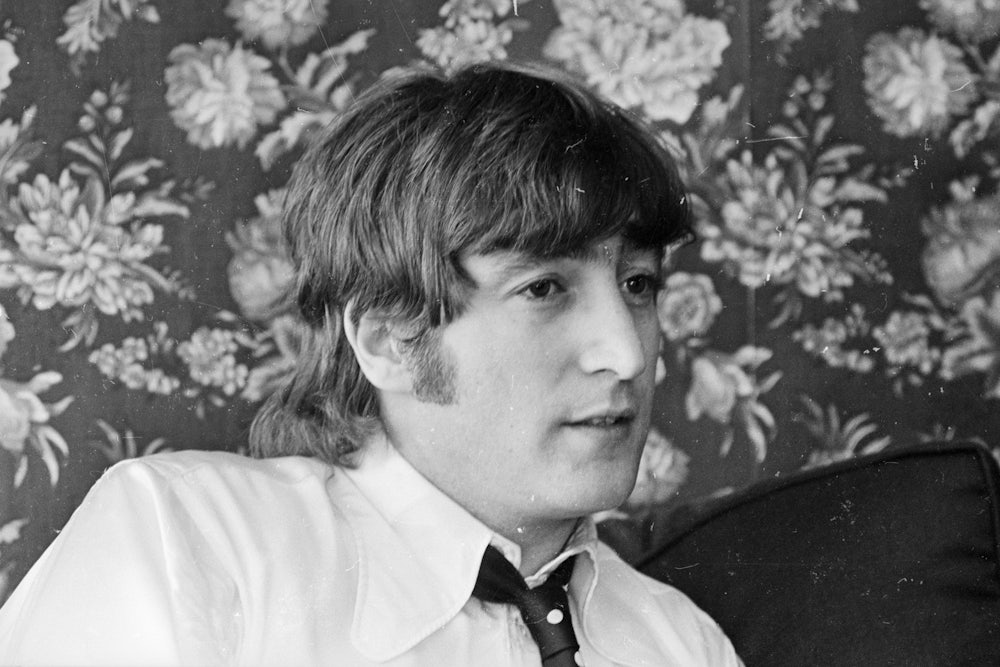

We know how old John Lennon would have been this Saturday—70—but who he would have been, we can only imagine. There were so many Johns: Teddy boy, moptop, Walrus, avant-gardist, Mr. Ono, politicker, house husband, and, finally, in the months before his death 30 years ago this December, model of middle-age content.

“Grow old with me,” Lennon once crooned into a cassette recorder he used for making quickie demos in his apartment in the Dakota. “The best is yet to be...” Lennon had started writing music again after several years of semi-retirement, and the new tune was one he never got a chance to record properly before he was shot by a demented fan on the sidewalk of his building.

He died too soon to grow old with his audience. Yet countless people who hold his music dear have been growing old with him. That is to say, Lennon’s public has been aging with him as an enduring presence in its lives, even as that presence has become progressively, sometimes strangely commercialized and often hard to reconcile with the realities of Lennon’s life and work.

Since the mid-’60s, when Lennon began leavening The Beatles’ moptop cheeriness with sober ruminations such as “In My Life” and expressions of doubt and anxiety such as “Help!” and “I’m a Loser,” his music was precociously mature. Reflective and self-critical, many of his songs had the point of view of adulthood, made palatable to teen fans through the incongruous bounciness of The Beatles’ music. Paul McCartney drew from the adult world—particularly from the pre-rock music of his parents and grandparents, in songs such as “When I’m Sixty-Four” and “Honey Pie”—but in service to nostalgia or sentiment. Paul was old-fashioned, John an old soul. Lennon made music to grow up by, and young people of several generations now have grown up following his lead.

I was born almost 20 years after Lennon, and I discovered The Beatles quite a while after Beatlemania. Still, like my own children, who came to The Beatles more than a decade after Lennon’s death, I derived from John’s Beatles songs a sense that adulthood was neither an ideal of lovey-dovey bliss or a joke (the dual message of Paul’s tunes), but something complicated and forbidding but within my capacity to grasp and maybe even bear.

Aware of his influence and duly terrified by it, Lennon made his infamous comment about The Beatles being “more popular than Jesus” as a distress signal, a warning to Beatlemaniacs (and no doubt to himself) of the hazards of pop idolatry. In later remarks, he showed that he saw the mammoth scale of his fame as life-threatening, although he perceived only some of the dangers of celebrity and never protected himself from the dark potential of fandom, its closeness to fanaticism. “The king is always killed by his courtiers,” he told an interviewer after Elvis Presley died. “The king is overfed, overdrugged, overindulged—anything to keep the king tied to his throne. Most people in that position never wake up.”

Lennon, in his savviness and cynicism, understood how the celebrity culture carries risks of early death—literal death, creative death, or death of the spirit—at the same time it glamorizes that death. “The biggest prize is when you die—a really big one for dying in public,” he said in the Playboy interview he did a few months before he died. “Okay—those are the things we are not interested in doing.”

He never wanted a death cult, nor a cult in life; Lennon wanted to live, like the rest of us—very much like the rest of us or, more precisely, how he imagined non-celebrities to be living. The life he sought in his last years was essentially a model of middle-age domestic tranquility, a dream vision of ordinariness enacted by an extraordinary man. He rambled around the rambling apartment he shared with Yoko Ono and their young child, Sean; he baked bread; he strolled his son around Central Park and took him to the YMCA for swimming lessons; he watched television and listened to Bing Crosby records. Apart from his having an avant-garde artist wife to handle the business affairs and his having gotten out of the house sometimes to make hit records, Lennon was essentially living the same life as my Aunt Rose.

He seemed to find contentment in an almost parodically conventional grown-up life, a proto-Reagan-era paradigm of domesticity, though his case is radicalized, arguably, by the fact that he was a male rock superstar rather than an Italian-American seamstress like my aunt. That was the last Lennon, apparently the Lennon whom John most wanted to be.

That Lennon is largely forgotten today and virtually absent from the images of John on the t-shirts and screen savers that fuel the public consciousness. Branding both Lennon and the people who wear and use them, the representations of Lennon pervasive today depict him in his most overtly radical phase, handily abandoning the ambiguity and the irony of his original messages. We see him in the pseudo-military gear he fancied in the early ‘70s, with the single word “Revolution” below the picture. (Lennon’s lyrics to the song “Revolution” were mostly anti-revolution.) We see him bearded and grim over the phrase “Working Class Hero.” (Again, the actual meaning of the song, which was fiercely sardonic, is lost.) And we see him as he looked before Sean’s birth, in sun-glasses and that sleeveless white “New York City” t-shirt, his arms crossed, his expression blank.

The songs he wrote in his final years are musical testaments to the traditional conceptions of adult normalcy that he seemed to revel in as he approached middle age. He wrote love songs to his wife as syrupy (if not quite as silly) as McCartney’s valentines to Linda (“Woman”), pretty lullabies to his son Sean (“Beautiful Boy”), and paeans to middle age (“Watching the Wheels” and “Borrowed Time”). “Good to be older,” he sings (in “Borrowed Time”), “Less complications, everything clear.” Among the songs like “Grow Old with Me,” which Lennon recorded only as a homemade demo, was a buoyant, tuneful country song in the vein of a Hank Williams tune. It was called “Life Begins at 40,” and this is how it starts:

They say life begins at forty

Age is just a state of mind

If all that’s true, you know that I’ve

Been dead for thirty-nine