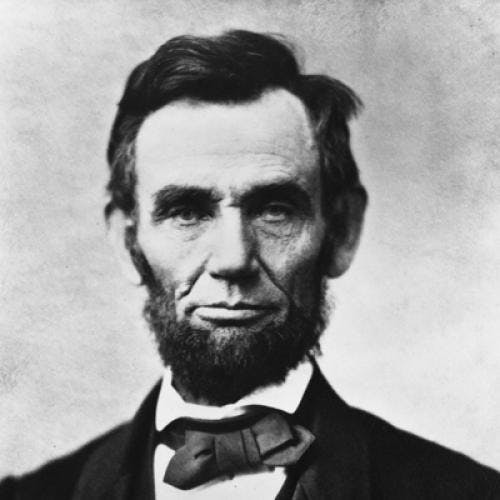

In listening to John Drinkwater’s legendary drama of Abraham Lincoln, I found obtruding upon my mind an irrelevant and disconcerting observation. I was watching the performance of a play about the life of the man whom the American people have canonized as half hero and half saint. He had earned their gratitude by helping them to steer a true course into and out of a civil war, which, had they gone astray, would have shattered the moral and political continuity of American national life. A new generation of his fellow-countrymen had just emerged as one of the victors in another war—one of the most bloody and costly which history has to record. Yet this play contained passages in which their national hero rebuked an attitude of mind towards the war of his day which no actor could have repeated with safety on the stage in any large American city during the war of our day. He said to Mrs. Blow, “You come to me talking of revenge and destruction and malice and enduring hate. These gentle people (the pacifists) are mistaken, but they are mistaken cleanly and in a great name. It is you that dishonor the cause for which we stand.” No actor would have dared, we repeat, to speak these words on an American stage during the war. The prevailing opinion in America had yielded utterly to the obsession of fear, destruction and hatred which Lincoln rebuked in the person of Mrs. Blow. It treated the pacifists whom Lincoln defended as morally contemptible criminals. It foamed with abuse for those Americans who were trying to keep alive during the new war, as Lincoln did during the old, the spirit of “just and merciful dealing and the hope of love and charity on earth.” The discrepancy between the moral attitude of the greatest American national hero towards the war of his generation was flagrant and complete.

The contrast illustrates a characteristic of Lincoln’s which his biographers have never sufficiently emphasized. His mind was capable of harboring and reconciling purposes, convictions and emotions so different from one another that to the majority of his fellow-countrymen they would in anybody else have seemed incompatible. He could hesitate patiently without allowing hesitation to become infirmity of will. He could insist without allowing insistence to become an excuse for thoughtless obstinancy. He could fight without quarreling. He could believe intensely in a war and in the necessity of seeing it through without falling a victim to its fanaticism and without permitting violence and hatred to usurp the place which faith in human nature and love of truth ordinarily occupied in his mind. When, for instance, the crisis came, and the South treated his election as a sufficient excuse for secession, he did not flinch as did Seward and other Republican leaders. He would not bribe the South to abandon secession by compromising the results of Republican victory. Neither would he, if she seceded, agree to treat secession as anything but rebellion. But although he insisted, if necessary, on fighting, he was far more considerate of the convictions and the permanent interests of the South than were the Republican leaders, who for the sake of peace were ready to yield to her demands. In the same spirit he insisted during the war on continuing the fight until the South was ready to return to the Union without conditions and to free the slaves. But his determination to fight until the Northern army had overcome the obstacles to the vindication of the political objects of the war did not interfere in his mind, as it did in the minds of so many bitter-enders, with “the hope of love and charity on earth and the spirit of just and merciful dealing.”

It is not only, however, that he harbored purposes, convictions and feelings which were incompatible one with another in the minds of other people. He expressed and acted on these usually incompatible motives and ideas with such rare propriety and amenity that their union in his behavior and spirit passes not only without criticism but almost without comment. His fellow-countrymen, who like to consider him a magnified version of the ordinary American and to disguise flattery of themselves under the form of reverence for him, appear not to suspect how different he is from them. He seems to them a simple man whose feelings, motives and words are composed of familiar and homely material and whose values they can sum up in a few simple formulas. He is a simple man in the sense that power, responsibility and intensity of personal experience never divided him from his own people who had none of these things. More than any other statesman in history he is entitled to their trust and veneration. But he was not a simple man as simplicity is ordinarily understood. He was an extremely complicated and sophisticated product of a kind of moral and mental discipline which sharply distinguishes him from his fellow citizens both of his own day and today. His simplicity was not a gift. It was an expression of an integrity of feeling, mind and character which he himself elaborately achieved, and which he naturalized so completely that it wears the appearance of being simple and inevitable.

The ordinary characterization of Lincoln as “a man of the people,” who rose by his own efforts from the humblest to the most eminent position in American life interprets him as a consummate type of the kind of success which all Americans crave and many achieve. The superficial facts of Lincoln’s life verify this interpretation, but it is none the less profoundly untrue. He did, of course, rise from the occupation of a rail-splitter to that of President of the American Republic. He could not have won the confidence of his fellow-countrymen unless he had appropriated all that was wholesome and fruitful in their life and behavior. He shared their kindliness and good nature, their tenacity of purpose, their good faith and, above all, their innocence. His services to his country and the achieved integrity of his personal life depended on his being good natured, resolute, faithful and innocent. But these comparatively common traits were supplemented in his case by others of a very different complexion. By some miraculous flight of the will he had formed himself into an intellectually candid, concentrated and disinterested man and into a morally humane, humble and magnanimous man. These qualities, which were the very flower of his personal life, neither the average nor the exceptional American, of his day or our day can claim to possess. Not only does the American fail to possess these qualities but he either ignores, misunderstands or disparages them. His deepest convictions stamp the average man with more energy and adaptability than his fellows, as the representative democrat and the ordinary aggressive successful climber, as the admirable national type. Lincoln was not at all like that. Yet his fellow-countrymen praise and reverence him just as if he was what they take him to be.

While Americans do not understand how complicated, many-sided and distinctively individual Lincoln is, his influence on them is the child as much of his many-sidedness as it is of his deceptive simplicity. They find in his words or in his actions, just as they do in the words and actions of Jesus, persuasive precedents for very different kinds of behavior. During the war, for instance, those who wished to fight on to the finish, those who considered it essential to keep political discussion alive and subordinate military action to political purposes, and those in whom war did not extinguish the spirit of fair play and good will—people who represented all these divergent points of view found consolation and support in Lincoln’s deeds and phrases. In our own day he serves almost

equally well as the prophet both of conservatism and radicalism. The National Industrial Conference Board has issued a leaflet, intended obviously for circulation among wage earners, in which Lincoln figures chiefly as the spiritual forerunner of Calvin Coolidge. They quote him as the advocate of hard work, thrift, the indefeasible right of private property and law and order, and the quotations are, of course, unimpeachably authentic.

But the Labor party of New York carries on its letterhead an emphatic affirmation by Lincoln of the prior claim of labor as compared to capital on the product of industry; and the New York World reproduces a passage from the First Inaugural about the right of revolution, which, if uttered by an alien, would render him liable to deportation and which would be condemned as seditious by the proposed Congressional legislation.

The interests, the sects and the parties all labor to exploit for the benefit of their own propaganda the name of Lincoln, but although they can usually find sentences and acts which they construe for their own benefit, the man himself as a spiritual force always breaks out of the breastworks of any particular cause. He never purveyed one particular political, moral or social specialty. His generation was particularly given to spiritual sectarianism and social crotchets. He himself was extremely accessible to generous emotions and humane ideas. But he was too complete a man to allow his mind to pass into the possession of any cause. And just as he freed himself from the obsessions of the reformer, so he was also too much of a man to yield to the weakness of a tolerant and balanced intelligence and take refuge in intellectual eclecticism. He was first of all himself. With the tact of moral genius he appropriated all that he needed from his surroundings and dismissed apparently without hesitation or struggle all that was superfluous and distracting. Whatever he appropriated he completely domesticated in his own life. The memory of Bismarck belongs chiefly to the German national imperialists; the memory of Gladstone belongs chiefly to laissez-faire liberalism; even the memory of Washington belongs more than anything else to the successors of the Federalists. But the memory of Lincoln belongs to all his fellow-countrymen who can guess what magnanimity is. Alone among modern statesmen he is master of every cause and every controversy which entered into his life. He did not flourish principles which he had not assimilated. He never relaxed his grip upon a truth which he had once thoroughly achieved. The action of his mind was always formative. Instead of being enervated and cheapened by its own exercise, as it was in the case of so many of his contemporaries and successors, it waxed steadily in flexibility, in concentration, in imaginative insight and in patient self-possession.

Hence it is that Lincoln is at once the most individual and the most universal of statesmen. In externals he fairly reeks of middle Western life during the pioneer period. No man could reflect more vividly the manners and the habits of his day and generation. He is inconceivable in any other surroundings. But with all his essentially and intensely middle Western aspect, he achieved for himself a personality which speaks to human beings irrespective of time and country. Already he is being more carefully studied and more discriminately appreciated in England than in America, and the interest of Englishmen is prophetic of that of other peoples. Wherever throughout the world democrats look for a hero or a seer whose life and sayings embody the spiritual promise of democracy, they will turn to Lincoln. They will turn to him because, essentially American as he was, and subject as he was to all the ambitions and distractions of a democratic political leader, he embodies none the less the permanent type of consummate personal nobility. He had attained the ultimate object of personal culture. He married a firm will to a luminous intelligence. His judgments were charged with momentum and his actions were instinct with sympathy and understanding. And because he had charged himself high for his own life he qualified to place a high value on the life of other people. He envisaged them all, rich and poor, black and white, rebel and loyalist as human beings, whose chance of being something better than they were depended chiefly on his own personal willingness and ability to help them in taking advantage of it.

Finally Lincoln obtained the mastery of his own life not merely or chiefly as the result of tenacity of purpose and strength of will. When the Divine Comedy of the modern world comes to be written, we shall find all the houses in one of the suburbs of Purgatory occupied by people who were esteemed during life chiefly for strength of character. It was his intelligence and insight which humanized his will. Not only were his peculiar services to his fellow countrymen before and during the Civil War born of his ability to see more clearly and think harder than the other political leaders, but the structure of his personal life and the poignancy of his personal influence depends most of all on the quality of his mind. It was his insight which enabled him to keep alive during the Civil War the spirit of just and merciful dealing and the hope of love and charity on earth. He knew that without just and merciful dealing human nature could not be redeemed in this or in any other world, and because he knew this, the goblins of war could not lead him astray. Both the integrity and the magnanimity of his life were born of this humane knowledge. Others willed when he did not and much good their willing did. But he knew when others did not know and he knew the value of knowledge. In a neglected passage of one of his last speeches he recommends to his fellow countrymen the study of “the incidents” of the Civil War “as philosophy to learn wisdom from and none of them as wrongs to be revenged,” That sentence furnishes the key to the interpretation of Abraham

Lincoln. He studied the incidents of his own life, of the lives of other people and the life of his country not as an excuse for revenge or for any kind of moral pugnacity or compensation, but as a philosophy to learn wisdom from. His fellow countrymen revere his memory but in studying the incidents of their own war they are far from either accepting his advice or following his example.