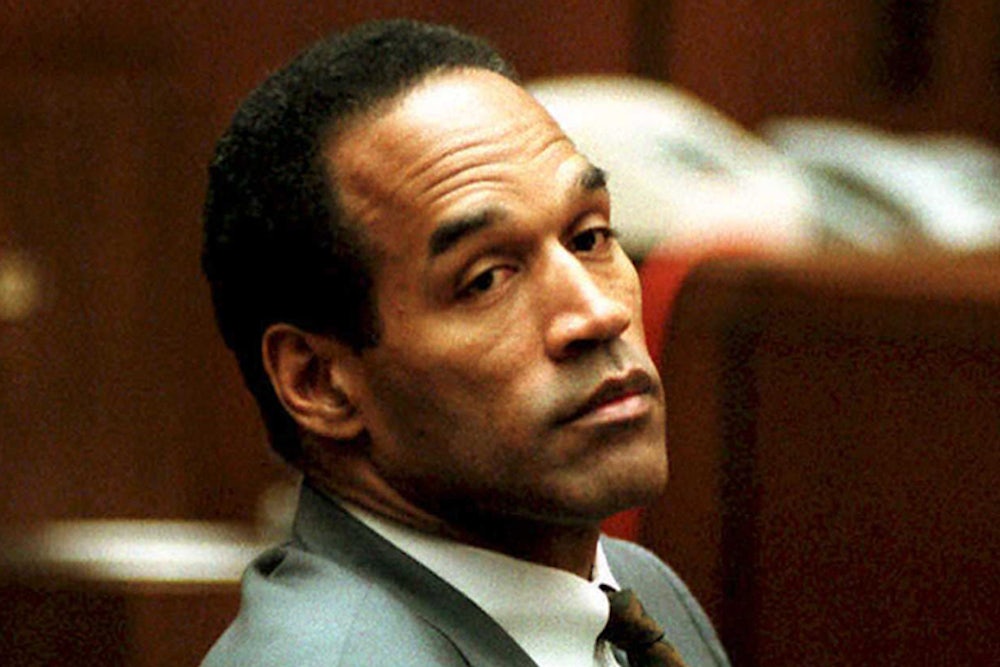

Among the legions of devotees of the O.J. Simpson trial in the United States, some of the most devoted are the five classes of sophomores I teach at an inner-city high school in Jersey City. For my students, the Simpson trial is something of an obsession, a sentiment that is, I concede, encouraged by this self-confessed O.J. junkie. This fascination is not simply prurient or voyeuristic (though there is no doubt some of that); the trial has been a terrific teaching tool that has helped to illuminate aspects of the American history curriculum I teach. For one, the interest the students show in the case facilitates--and enhances--their understanding of the criminal justice system. Because of the O.J. case, they understand the multifaceted meaning of the jury system; the role of the judge, lawyers and witnesses; how and why evidence is admitted and impeached; and the significance of terms such as direct examination, cross-examination, contempt of court, hostile witness and many more. And there is more. Kids love history when they can see justice and injustice, fairness and unfairness in it--and when they can take sides. O.J. allows them to do that, and about far more than just the trial itself.

The best example is provided by the Constitution, on which we spent more than two months. Amendments four through eight are about crime, and O.J. was the vehicle for studying them. Take the discussion of the jury as delineated in the Sixth Amendment. We covered this amendment in early January, which was perfect because that was when Robert Shapiro was demanding that O.J. be tried right away. My kids reasoned immediately: Shapiro wants a speedy trial, just as the amendment says. Right. But the “public” aspect of the “speedy and public” trial part of the amendment caused some disagreement. This amendment, Rhonda declared, makes no sense. Why? I asked.

“It says you get a ‘public’ trial in front of an ‘impartial jury,’ right?”

“Yes.”

“How is O.J. going to get an ‘impartial jury,’ if the trial is in ‘public’? Everyone in Los Angeles knows about the case, and the media is making it worse. Ain’t no way O.J. is going to get a fair trial under these conditions.”

“If it was not public, Rhonda,” Walt added, “we wouldn’t be able to talk about it all the time.”

“It’s not for your amusement, Walt,” Rhonda shot back. “It’s for O.J.’s innocence.”

That, for my students, is no laughing matter. No more than four of my 110 students think O.J. Simpson is definitely guilty and few are willing to admit the possibility that he might be. This faith in Simpson is strongest among black girls. They enforce something resembling social control to govern opinions on the case. One girl last week suggested, hey, the case against O.J. isn’t that crazy. Bad move. She was viciously attacked until she admitted that, yes, she was just kidding: of course O.J. is innocent.

Why is O.J. so important to them? All but a few of my students are black or Hispanic, and O.J.’s is a racial case. They have a substantial emotional investment in Simpson’s innocence, the origin of which is not clear. When I mention that I think O.J. is guilty, they dismiss my opinion with a smile accompanied by the explanation that, of course, I wouldn’t understand. Though my students identify with Simpson on racial grounds and for racial reasons, they must not have internalized the case too deeply because they are not offended at my belief in Simpson’s guilt. I am merely naive, nothing worse. And at least I admit that O.J. will never be convicted, even though I am wrong in believing that he is guilty.

Why, my students asked, do you think that O.J. will not be convicted even though he is guilty? Simple, I replied. At least one juror is bound to hold out. While almost all disagree with me about O.J.’s guilt, my contention that he will be acquitted regardless has produced some spirited discussion. Wanting to explore this issue, I handed out an article from The New York Times by Kenneth Noble that showed that the overwhelming majority of blacks believe O.J. to be innocent, while the inverse is true among whites. Many students reacted viscerally to this, charging Noble with everything from “racism” to “ignorance” to being a “poor writer.” While my students are well aware of the role of race pervading the case--especially in the relationship between Nicole and O.J.--they refuse to concede that the jurors might vote for O.J. because he is black. The notion that some blacks might vote to acquit O.J. because of his race is, to these students, profoundly offensive. Race might be a reality in this case in a thousand small ways, but it will in no way affect the ultimate decision of the jury. They insist that their belief in O.J.’s innocence has nothing to do with his race. O.J. should get off because he did not kill Nicole and Ron.

But they are not willing to leave it at that. Like most observers of murder trials, my students have a psychic need to find the real killer; such crimes cannot go unaccounted for. My students are more than willing to supply the real culprit. One student suggested that Ron Goldman killed Nicole before killing himself and then throwing away the knife. Another believes the dog did it. Shenia suggested that Al Cowlings, Simpson’s best buddy, did it. Bryant believes the killer is O.J.’s son. Philip blames “that fag dude who wants to marry O.J.”; that would be Kato Kaelin, Simpson’s houseguest. Even the smartest students are willing to give more credence to the most outlandish theories than to the prosecution’s.

Jon, a bright student, had his own scenario: O.J. was shaving and cut himself. Kato took the blood from the shaving cut, brought it to the crime scene and dumped it. Why, I asked, did O.J. collect his blood after he cut himself shaving? Jon called me a racist, and that was that. When Jon or others call me a racist, it is not meant viciously. They know that I cannot be a racist (what kind of racist would want to teach at their school?), and this charge is always leveled without rancor. It is usually a shorthand way of saying, “Shut up. I don’t want to continue this discussion anymore.”

For instance, another student, Bryant, called me a racist in one such discussion last week. “How, Bryant, can you call me a racist for thinking O.J. is guilty? Shenia thinks O.J. is innocent, but she thinks that A.C. did it. A.C. is, of course, black.”

“That’s O.K. for Shenia. She black. You ain’t.” True enough.

While no non-white student believes O.J. did it, few are upset about the crime itself. Simply, they do not like Nicole; again, this sentiment runs especially strong among black girls. Many students disapprove of interracial relationships, and this accounts for some, though not all, of their animus toward Nicole. Because O.J. is the accused in a trial that has assumed such racial significance, my students cannot take their anger out on him. So they dump it all on Nicole.

How? Eunicia said that Nicole got what she deserved as a result of messing with a black man. Wait, I said, if you think that it is wrong for O.J. to marry a white woman, doesn’t he deserve some of the fault? No, Eunicia added. Women control these types of situations, and Nicole roped O.J. in to get his money. If it weren’t for Nicole, O.J. would have stayed with his first wife, Marguerite, who, of course, was black.

But wait, I pressed. When O.J. left Marguerite for Nicole, O.J. was a national hero and Nicole was just a kid--just a few years older than you, in fact. Can’t you imagine a situation in which Nicole was so awed by O.J.’s fame and fortune that she simply fell for him? No, again, I clearly did not understand. Nicole was the woman, and O.J. was the man. If the relationship was ill-fated from the start, there is no question whose fault it was.

What, I asked all my classes, about the beatings? Even if you do not believe that the prosecution has proved its case, you can surely deplore the wife-beating that no one denies.

“Wrong,” Shenia responded, “the beating did not bother Nicole too much, so why should it bother me?”

“Why,” I asked, “do you think the beatings did not bother Nicole? She sounded quite frantic and desperate to me on that 911 call.”

“It was just for show. Otherwise, she would have left him.”

Another student pointed out that, in fact, Nicole did leave. But no matter, according to Shenia: she did not leave soon enough. If she did not leave immediately because she wanted his money or fame, then she was playing with fire--and we all know what happens to people who do that. The discussion continued from there.

Sholanda: “Look at what has happened since the marriage. Nicole was a slut. She gave some other guy oral sex in O.J.’s house. She had many lovers--even before she and O.J. married! It is only right that he became very jealous and took out his jealousy in some way.”

Eunicia: “Nicole stayed, didn’t she? If she didn’t like it, why didn’t she leave?”

Sylvia: “If Nicole were a black woman, she would have fought back. No black woman would take that.”

Maxine echoed an especially common belief: “Nicole hit O.J. first. Of course he was going to hit her back. If she did not want to be hit, she should not have hit him first.”

I was somewhat shocked the first time I heard this. “Maxine! Don’t you think it is one thing for a woman to hit a man and another for a man to hit a woman?”

She looked confused. “No.”

Usually I let opinions fly freely, but I decided to draw the line here. “Listen. Under no circumstances ever is it O.K. for a man to hit a woman. If a woman hits a man, he should at most gently restrain her, but never, never hit her.”

Maxine and the others were unconvinced. “Mr. Gerson, why do you say that?”

“It is very simple. Men are stronger than women. Much, much stronger.”

“Then you obviously have not seen the women in Jersey City.”

While my students view everything through the prism of race, they are hardly concerned with gender at all. Not one black girl identifies with Nicole as a woman; they identify instead with O.J. as a black person. Intellectually convinced that there are few significant differences between men and women (even when brute force is an issue as with O.J. and Nicole Simpson), they may not, I am afraid, have the basis to back up their distrust of men with action or, more accurately, non-action in their personal relationships.

The anti-Nicole bias is most prevalent in students from broken homes--which is most of them. Walt, a student from a strong two-parent family who is always vocal, honest and forthright, never complements his defense of O.J. with criticism of Nicole. He thinks that Kato did it. Nicole is the unfortunate victim, in no way an accomplice to her own murder. But this is reflected in Walt’s personal life; when he wants to date a girl, he writes her impassioned, eloquent love letters. He knows how to treat women, and he knows that O.J. does not.

How about Ron Goldman? Though he is clearly a big player in this drama, he is only mentioned in relation to Nicole. Was he sleeping with Nicole? How did O.J. kill Nicole if Ron was there with her? In ignoring Goldman, my students are doing just what the nation is doing. Maybe we ignore him because he is rarely mentioned in the news media; maybe we ignore him for the same reasons the media does (whatever they might be). But it certainly is strange that Goldman, as much a victim as Nicole, is rarely mentioned, and the tragedy of his death is rarely felt. I wanted to discuss this with my kids, but did not know the answer myself, nor even where to begin to look for answers.

My students are unimpressed by the defense team and have not made a hero out of Johnnie Cochran, as Kenneth Noble reported many blacks in Los Angeles have. They admire Cochran’s courtroom techniques but no more so than those of prosecutors Christopher Darden or Marcia Clark. They are disgusted by the evasions and mistruths that have characterized the arguments from the defense team, though I admit that my relentless exposition of their deplorable conduct may have been a factor here. I also admit being a bit embarrassed at the way I handled the preview of F. Lee Bailey’s cross-examination of Mark Fuhrman. Bailey, I explained, is a living legend--the best cross-examiner in the world--and someone they should watch and be prepared to tell their grandchildren about. Bailey had said, after all, that he was going to perform a “character assassination” of Fuhrman, and this was going to be entertaining if nothing else. Most were excited, did their homework and came back wondering what I was talking about. I came back wondering the same thing.

Though they believe Mark Fuhrman to be a vile racist, most of my students were impressed by his deftness on the stand. One of O.J.’s most fervent supporters in my top class came in after Fuhrman’s first day of his cross-examination with a definitive judgment: that racist detective is slick. No argument there; my kids know a smooth character when they see one and will always accord him at least grudging admiration.

The Fuhrman testimony brought to light a deeper issue that tapped a nerve center for my kids: the police. My students have an ambiguous, complicated relationship with the police. On the one hand, several have police officers in their families and greatly respect the work they do. They know a lot of bad guys in jail and are grateful to the police for seeing to that. However, they see violent crime in their neighborhoods every day and are at a loss to why such blatantly illegal conduct exists in such plain view. An immediate answer is the racial one: my students believe that if their neighborhoods were white, the police would crush the crime. I was not in Jersey City during the Rodney King trial, but it occupies a major place in the psyches of my 15-year-old students; it tells them that the police are capable of vicious racism. Rodney King touches the rawest emotions, which in turn trigger a host of anti-police and anti-authority sentiments bathed in racial hostility.

This confusing array of emotions bodes well for O.J. While my students do not regard police as foot soldiers for a racist enterprise, or even necessarily as racists themselves, they are suspicious enough to blame the cops for aspects of the case that incriminate O.J. The police do not have to be in a conspiracy against blacks or O.J. to plant evidence. How, I have asked over and over again, did O.J.’s glove land in his backyard? Easy--the police planted it. How did O.J.’s blood get on the glove alongside that of Nicole and Ron? Simple--the police did it. How did the police get O.J.’s blood to plant it? Jon reiterated his shaving-cut theory, surmising that Kato and the police were in cahoots on this. How, I asked, did Kato apply the chemical solution needed to preserve the blood? Mr. Gerson, he responded, these are the police. They can do anything.

Bailey was certainly responding to this ambiguous relationship that many blacks have with the police, but his tactics did not impress my students. They were neither moved nor shocked by his constant invoking of the “N” word (maybe because they use it so much themselves) and never sympathized with Bailey. Bailey’s theory that Fuhrman put O.J.’s glove in his sock like a Marine and subsequently dumped it at O.J.’s house--getting blood in the Bronco at some point--was neither accepted nor rejected. As Walt said, “Well, it could have happened, right?” Can’t argue with that.

It was also Walt who came up with what I consider as damning a piece of evidence against O.J. as I have heard. Look, Walt suggested, at what happened when the cops called O.J.’s hotel room in Chicago to tell him, “Your ex-wife has been killed.” O.J. responded, “My God, Nicole’s been killed.” How, Walt asked, did O.J. know the cops were talking about Nicole and not Marguerite?

“Walt,” I responded, “that’s a terrific point.” One of the other students turned to Walt and asked, “Does that mean you think O.J. might be guilty?”

“No way.”