What the TV newsmagazines can’t tell us.

In 1968 a documentary producer at CBS News had the idea of creating a television show that would resemble Life magazine. The result was “60 Minutes,” the most popular TV news program in history. Its success transformed the television magazine from a conceit into a familiar journalistic form. Today these “magazines” include, in addition to “60 Minutes,” “20/20” on ABC, “1986” on NBC, and “West 57th,” a sort of yuppie cousin to “60 Minutes,” on CBS. Magazine-style TV journalism has had an influence on the evening news shows, which are running lengthier special segments—especially the recently expanded “MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.” Meanwhile, soft “back-of-the-book” stories have found a home on local “Evening” and “PM” TV magazines.

The magazine approach has proven to be far more commercially successful in television than it ever was in what must now be called “print” magazines. Because they are substantially cheaper to produce than entertainment shows (and, unlike most TV shows, are not the work of independent producers but of in-house network news divisions), even TV magazines with low ratings may make financial sense to network programmers. A top-rated magazine such as “60 Minutes” is a money machine; it’s been estimated that “60 Minutes” is responsible for more than half the profits of CBS’s broadcast division. Ironically, while the TV magazines thrive, most of the big-circulation general interest magazines that first inspired this trend in TV journalism have long since departed from the scene. Collier’s folded in 1957, the Saturday Evening Post in 1969, Look in 1971, and Life in 1972, just four years after “60 Minutes” was born. In the days before television, these magazines had been able to sustain enormous circulations because they were the most important medium for national, visually oriented advertising; radio could provide sounds but no headlines or pictures. Then came TV.

In their heyday in the 1940s and ‘50s, the “slicks” were a mixture of light features, profiles of sports heroes and movie stars, and more ambitious “hard fact” stories that addressed social problems, all generously illustrated (especially in Life and Look). The formula for the weightier reporting was to provide an accumulation of human detail derived from exhaustive legwork. In a forthcoming volume of memoirs, It Seems Like Only Yesterday, the writer John Bartlow Martin describes several such magazine stories that he produced during this period, mostly for the Saturday Evening Post. In one, for example, he profiled a 12-year-old boy found guilty of murdering a seven-year-old playmate and sentenced to 22 years in the penitentiary because Illinois had no reformatory.

The TV magazines learned from the sticks how to sell a story through people. They also learned from the picture magazines how to tell a story through visuals. Today, different magazine shows have tried to challenge, to various degrees, the constraints of print, increasing the emphasis on pictures and personalities and de-emphasizing words and ideas. Indeed, one show that has appeared sporadically on NBC, “Fast Copy,” seems premised on the notion that in the video age print is obsolete: articles that one might assume had already reached mass audience in magazines like Good Housekeeping and TV Guide are repackaged for TV and introduced by the magazines’ editors. (Both the magazine and the author of the original article get paid for this.) Print magazines are far from extinct, but it is arguable that just as TV has replaced magazines as the dominant mass medium for word-and-image advertising, shows such as “60 Minutes” and “20/20” have become the dominant mass medium for magazine-side journalism. Browsing through the electronic coffee table, it’s worth considering what’s been lost in the process.

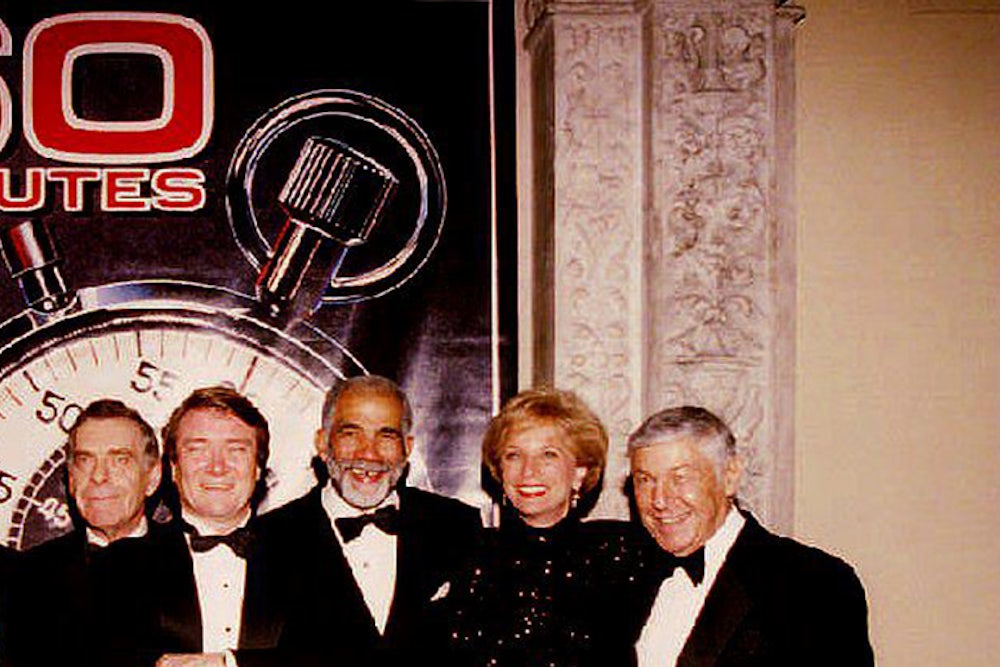

The first TV magazine—“60 Minutes”—remains the best. Since the program’s ratings took of fin the mid-1970s, intellectuals have tended to disdain it, but one suspects the program’s most vociferous critics haven’t spent much time viewing the alternatives. It is probably the least self-consciously video-minded of all the TV magazines; at a time when TV news programs emphasize flashy computer graphics, “60 Minutes” sticks to its stopwatch logo and black background. Words matter on “60 Minutes.” In his bok, Minute by Minute, Don Hewitt, the show’s executive produce (that is, editor in chief), writes: “I am a bug on audio, convinced it is your ear as much as your eye that keeps you glued to a television set.”

To a great extent this means fussing over pauses and inflections, but Hewitt’s obsession with audio also affects content. The writing on “60 Minutes” is simple and direct, guiding the viewer from idea to image with a minimum of hype. A good example was the “lead” to a story by Morley Safer about the burning of Indian brides whose families can’t pay large dowries. Instead of florid denunciations of savagery and horror, Safer began by introducing two Indian feminists. “They are not trying to provide something as luxurious as an equal rights amendment or end harassment in the workplace,” he said. “They do not contemplate the sex of God or whether women should be called Miss or Ms.,” he continued, with just a hint of weariness. “Their work is more elemental. They are trying to stop this.” There follows a succession of five black-and-white still photos of women who’ve been burned to death.

“60 Minutes” has a sure instinct for a good story. A 1971 segment revealed that many liberal supporters of busing (Teddy Kennedy, Ben Bradlee, Thurgood Marshall, Tom Wicker) sent their children to private schools. A 1980 segment told the hair-raising story of an insane man who, despite his repeated threats and attempts to kill his ex—wife, was granted a one-day furlough from a mental hospital and carried out the threat. More recently, the focus of the show has been a bit softer, with more celebrity interviews. And the celebrities chosen to be interviewed (Johnny Carson, Jackie Gleason) don’t seem quite as tony as those considered profile material in the old days—Leopold Stokowski or Fedrico Fellini holding forth while the correspondent, perched on the edge of his seat, smiled tightly. (Those high-culture interludes seemed to make Dan Rather especially tense. Still, “60 Minutes” continues to track down stories that don’t make their way into newspaper headlines. Recently, for example, it did a fine piece on preparations in Nicaragua to wage war against American troops.

THE ANTITHESIS OF “60 Minutes” is CBS’s new “West 57th.” The program’s opening sequence is a gaudy celebration o the joys of video, taking us breathlessly behind the scenes with elaborate crosscutting between correspondents discussing their stories, clips from the stories themselves, and control-room hubbub: “You have to wait for me to get to speed. Give us the top! Give us anything ! Give us something!” In addition to fast cutting, “West 57th” keeps the individual stories shorter. “60 Minutes” will present three stories in an hour (plus a mercifully brief humor essay by Andy Rooney). “West 57th” does four or five. Plowing through transcripts of both shows, I found it would take me about 20 minutes to read an episode of “60 Minutes,” but I could knock off a “West 57th” in ten. Av Westin, executive produce of ABC’s “20/20,” explained to me what he saw as the difference between “60 Minutes” and “West 57th”: whereas “60 Minutes” squeezes down what would ordinarily be hour-long documentaries into tight 20-miute segments, “West 57th” inflates three-minute stories from the evening news into ten-minute segments.

One reason “West 57th” stories zip along so quickly is that interjections in the form of stand-up or voice-over narration are kept to a minimum. The word-to-picture ratio is heavily weighted toward pictures. The style resembles cinema verite, but paradoxically the result often seems phony. When so much importance is given to getting the story as it happens, the correspondent must struggle not merely to interview but to “interact.” When this comes naturally, fine. During a “60 Minutes” interview, Lena Horne, talking with Ed Bradley about her struggle for acceptance in the white world as the two of them strolled through a park, impulsively reached for his hand. Because the gesture was genuine, the footage was touching. But “West 57th” strained for false intimacy. For example, during an apparent lull in a story on Garland Bunting, an old-time liquor control agent on the trail of illegal stills in North Carolina, Meredith Vieira, an attractive and, on the evidence of other segments she’s done for the program, intelligent reporter, suddenly and inexplicably started flirting:

Vieira: But Garland if I were to move to North Carolina and set myself up with a little still, do a little business, would you arrest me?

Bunting: I wouldn’t have no alternative. You know, I’d arrest my mother if she set one up in here.

Vieira: No, you would not!

The subject matter of “West 57th” reflects a medium-is-the-message philosophy. In its brief life span, the show has already done two stories on music videos and one of the expansion of pornography into the video market. Even a profile of Danny Sullivan, winner of the 1985 Indianapolis 500, focused not on what it’s like to be a race car driver (which would have been fun to learn about) but on the endorsement racket. This allowed us to see Sullivan doing several takes of an Alberto VO-5 commercial. “West 57th” has done some serious stories—a piece on the availability of machine guns, for example, and another on Los Angeles’s tough enforcement of toxic waste laws—but overall the show leaves an impression that what it is really about is itself.

ABC’s “20/20” occupies a middle ground between “60 Minutes” and “West 57th.” Its word-to-picture ratio resembles that of “60 Minutes”; reporters are permitted to spend a little time paraphrasing abstract material through narration and stand-ups. This allows “20/20,” which usually runs three or fewer pieces per show, to take on ambitious stories. Indeed, “20/20” often outdoes “60 Minutes” in the quality of its investigative reporting. For example, long before the spare parts scandals became page-one news, Geraldo Rivera did a segment on George Spanton, a Pentagon auditor who blew the whistle on Pratt & Whitney, a key spare parts contractor. More recently, Sylvia Chase did an impressively thorough job of exposing how the Mafia was using Midwestern pizza parlors as fronts for selling heroin.

But “20/20,” like “West 57th,” relies heavily on flash. Much of this is a simple result of network scheduling. While “60 Minutes” airs Sunday at 7 p.m., “West 57th” and “20/20” (and for that matter, NBC’s “1986”) are in prime-time slots, and Av Westin says the difference is crucial. “60 Minutes” comes on during a time period restricted by the FCC to local programming, with exceptions for network children’s shows, documentaries, and public affairs programs. It also airs on the day when people go to church and read the Sunday newspaper. “ ’60 Minutes’ is a Sunday, go-to-meetin’ absolution,” says Westin. “20/20,” on the other hand, appears on Thursdays at 10, opposite “Knott’s Landing” and “Hill Street Blues.” As a result, “what we did to survive was to play for more of the entertainment values. We play more for emotion.”

ON “20/20” THE GLITZ is not so much in the visuals as in the words, which are more plentiful than on “West 57th” but less restrained than on “60 Minutes.” A substantial portion of the show is devoted to the exchange of gushy happy talk between the show’s two very visible anchors, Hugh Downs and Barbara Walters, and also between the anchors and individual correspondents, who are always “debriefed” after their segments. It is not enough that we be moved—as well we should be—by the efforts of New York City ghetto schoolchildren to raise money to transport grain to Ethiopia, the subject of a special hour-long edition in 1985. It is not even enough that we watch the children watch footage of their grain being delivered (another instance of “West 57th-style video obsession) and learn how moved they are: “It’s like, now I know what the real meaning of the word starvation is. You know, you come home from school, you say, ‘Mom, I’m starving.’ Well, we really don’t know what it’s like to be starving like that.” To make absolutely certain that we are all feeling the correct emotions, we must witness this exchange between the correspondent, Tom Jarriel, Downs, and Walters:

Walters: Tom, that was so moving for us here, I can imagine what it was like for you there.

Jarriel: Very much so, yes.

Walters: What has happened now? Have the children in New York finished with the situation, or—

Jarriel: The momentum of their drive is still going on, Barbara. In fact they’ve now got a quarter of a million dollars in contributions—they’re sending more food and buying two trucks for Ethiopia, which are badly needed.

Walters: Isn’t that wonderful.

Downs: That’s just marvelous.

“20/20” could use a bit more restraint in its story selection as well. The problem isn’t so much in the stories “20/20” does as in those it chooses to dwell on. A segment on New York City schoolchildren raising money to buy grain for Ethiopia is fine, but a whole hour? (An hour about what caused the mass starvation to begin with and why government relief efforts have failed would seem more worthwhile.) “20/20” did not one but two stories on the McMartin Preschool child abuse case, God’s gift to the TV magazine shows (NBC’s “American Almanac” also weighed in). The second story served as the occasion to present lucid testimony from James Rowe, a former prisoner of war, to demonstrate that scare tactics allegedly employed by McMartin teachers—for example, slaughtering pet turtles and rabbits—were “curiously parallel to the classic brainwashing techniques used on prisoners of war.”

OF ALL THREE networks, NBC has had the most difficult time with the magazine form. Fourteen NBC magazine shows have come and gone since “60 Minutes” first appeared. The most recent attempt, “American Almanac,” was pulled off the air this past winter and reconstituted with “West 5th”-style New Wave graphics and staff changes as “1986,” which had its debut in June. “American Almanac” was intended to be calmer and more in touch with ordinary people’s lives than the other magazine shows. “Lush photography, and a feeling of quiet and sort of stateliness” is how Roger Mudd described the idea to Mary Battiata of the Washington Post. “Most of our television and most of our news moves too fast, and you’re force fed so much information that your system can’t digest it, and I thought that there should be some space, once a week … for things to slow down, so people could be a little more contemplative.” An obvious influence was “Sunday Morning” and its host, Charles Kuralt, who projects intelligence and an unforced affection for Americana derived from years of traveling across the country for his evening news “On the Road” stories. But the down-home format of “American Almanac” proved unconvincing. On the first program, Mudd announced, “We’d like this to be the sort of show you might hang on a nail by the kitchen door, if that were possible.” At the end of the show, Mudd bid viewers farewell, “Until the next phase of the moon.” At the end of another, he signed off by observing that 150 years ago that day, “John and Jane Clemens, residing in Florida, Missouri, had a son. Called him Samuel.” There aren’t many people who can pull this sort of thing off.

THE COMPARATIVE MERITS of print versus TV journalism are a reflection of the comparative strengths, and weaknesses, of pictures versus words. In certain ways, pictures are more honest. Consider the practice on some TV magazines of staking out the home or office of a guilty party who has refused an interview. When he shows up, you get some nice jerky footage of him mumbling “no comment” before he cups his hand over the lens. This is called “ambush journalism,” and it is many critics’ main complaints about the TV magazines. But print journalisms perform invisible ambushes all the time. Not many reporters make a point of identifying themselves to everyone they observe in the course of writing a story. And a surprising number make a habit of secretly recording phone interviews, a far more ethically questionable practice than TV ambushes.

Respectable brows also furrow over the various ways TV news distorts the truth. Quotations are taken out of context. Tight close-ups make bad guys look guilty. Interrogators get to reshoot questions while interviewees have to stand by what they said, unless they’re the good guys, in which case they get coached. Certainly there are abuses. In a libel suit filed by Dr. Carl Galloway against “60 Minutes,” a review of the outtakes revealed that one interviewee’s one-word answer, “yes,” had not been given to the question that appeared immediately before it was broadcast. (In his book 60 Minutes: The Power and the Politics of America’s Most Popular TV News Show, Axel Madsen speculates that the answer came in response to a crew member offering a cup of coffee.) On the whole, though, TV news is much more constraining to would-be falsifiers than print. “You print guys make things up all the time,” Don Hewitt told me when I interviewed him in his cluttered office at CBS. In It Seems Like Only Yesterday, John Bartlow Martin confesses that in the first magazine article he ever sold, written in 1938 about the Dominican Republic under Trujillo, he invented an anecdote about a girl getting raped by a soldier. “I never again invented an episode in a serious magazine piece, for it is a shabby trick, a counterfeit substitute for solid reporting,” Martin writes. Do you find yourself wondering what he meant by that qualifier, “serious”?

Outright fabrication or harder to detect phony “blind quotes” from anonymous sources or composites are impossible on TV. Janet Cooke would never have reported “Jimmy’s World” for “60 Minutes.” As Jeff Greenfield pointed out in a special navel-contemplation edition of “60 Minutes” in 1981: “One thing you don’t do with television cameras is find a nonexistent eight-year-old child on heroin. You can’t, unless you hired Gary Coleman.” To demonstrate how much easier it is to lie in print that with pictures, I invented that quotation from Don Hewitt in the previous paragraph. That interview never took place. I’m only guessing that his office is “cluttered.” Everything else in this story is true, but you’re going to have to take my word for it.

THE POINT IS that television is more reliably stenographic than print. Unfortunately, the dictation is performed by big, clumsy machinery—what TV people call the “thousand-pound pencil.” The machinery records the truth, but the truth that is there to record can’t help but be altered by the camera’s conspicuousness. Take ambush journalism. A more practical criticism is that, precisely because the camera is so obtrusive, the attempt to take a victim by surprise may backfire. On “West 57th,” Meredith Viand Garland Bunting, the North Carolina revenuer, ambushed a liquor still out in the woods. There was some great footage of Bunting sneaking through the woods and whispering to his men: “Y’all hold up right here [crinkle, crinkle]. Stay right here [crinkle]. Hold it, hold it.” On the voice-over, Vieira noted the danger of the operation. But when they arrived at the still, the bootleggers were long gone. Do you suppose it had something to do with the fact that Bunting had a camera crew in tow?

The same problem comes up when TV reporters go undercover to do a story. "1986" used this technique in a story about Florida's porous borders. "These three men could have been dropped by a Cuban or Soviet trawler," narrated Peter Kent over a picture of a speedboat racing through the Caribbean in broad daylight. In fact, they were hired by NBC to show how easy it is to slip past the Coast Guard. The boat did evade the authorities, but Kent had to concede, "Perhaps with our camera boat and the helicopter, we weren't suspicious enough." Perhaps?

A more subtle effect created by the presence of a TV camera is its tendency to change the way people talk when one is pointed at them. Active "coaching" by a correspondent or segment producer to say this or that may occur now and then, but the more common problem is the way questions are formulated to nudge the interviewee in the direction of cliches. On a "1986" segment about the physical abuse of teenagers who sign up with shady companies to travel around the country and sell door-to-door, Ed Rabel asked one teenager who had been badly beaten, "Now you had a dream when you joined this organization. What did you come away with?" The answer came right on cue: "A shattered dream." People don't talk like this in real life. But they do when they're on television. Television doesn't seem to mind. It is more important that an interviewee say something that helps tell the story, just as it is better to have footage of Garland Bunting sneaking through the woods or an NBC speedboat zooming into Florida, even when there's no payoff. The alternative is no sound bite and no action footage.

IF TV MAGAZINES change the truth and get stuck with the consequences, there is also a large slice of the truth that they don't get at all. Print magazines are distinguished from newspapers in part by their ability to explore things from an analytic point of view. This can be as simple as paraphrasing what someone says rather than using a quotation or one step up the ladder of abstraction, generalizing on the basis of what several people say or, one step further still, interpreting conflicting accounts to arrive at the truth. Each step carries you closer to the kind of subjective truth that TV is ill equipped to perceive or communicate. Part of the problem is organizational: TV news is collaborative. A story is the work not just of the correspondent but of the field producer (who usually puts in more time on the story than the correspondent himself), the researcher, and the cameraman, among others. ("60 Minutes," for example, has also used the Center for Investigative Reporting in Washington and the Better Government Association in Chicago to develop stories.) Obviously, a committee is not going to produce journalism that reflects idiosyncratic judgment.

Even if it could, it probably wouldn't want to, because to do so would require having someone look into a camera and talk at greater length than most people would care to listen. The introduction of computer graphics has made it easier for TV to deal with a certain kind of abstraction—economic statistics, for example. But less quantifiable ideas remain too elusive for the medium. Even the most word-oriented TV magazine, "60 Minutes” misses out on an important part of the story. Let me give an example I happen to be familiar with. About a year ago, 1 wrote a story for this magazine about a school for mercenaries in Alabama. "60 Minutes" soon followed up with a story of its own. I assume we both got interested for the same reason: the school had trained four Sikhs implicated in the bombing of an Air India flight.

THE STRENGTH of the "60 Minutes" segment was that it did what no print journalist can ever do: it took you right there, down to Hueytown, Alabama, and let you watch the proprietor, Frank Camper, fire off his automatic weapons in the woods and lead his recruits in a chant of "Vive la mort/Vive la guerre/Vive le sacre mercenaire" at the initiation ceremony at the local Shoney’s. Describing these things really can't match seeing them. But seeing Camper's school only gets you half the story—the less important half. Most people would want to know why a school suspected of training terrorists would be permitted to stay open. The answer, unfortunately, can't be photographed. You have to know that Alabama permits private citizens to own automatic weapons, which are not closely regulated by the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, and that semiautomatic weapons aren't regulated at all. You also have to know that the State Department has a hard time proving a violation of the Neutrality Act, which forbids American citizens to raise armies against nations with which the United States is at peace. There is also the issue of free speech: arguably Camper is well within his rights to tell anyone he likes how to go about killing somebody, provided he doesn't tell them to 80 kill that person. "60 Minutes" didn't provide these explanations, with the result that viewers were left with a vague sense that the system wasn't working and with no understanding of why, or if it could be made to work better by banning machine guns, for example.

As I watched other segments of "60 Minutes," "West 57th," and "1986," it occurred to me over and over that the 'why" was consistently missing from the story. "1986," for example, did a story showing that light trucks do not have the same reinforcement bar in their side doors that automobiles do. As a result, they are more dangerous. Why won't the Department of Transportation do anything about this? Connie Chung's answer? "Elizabeth Dole refused our repeated requests for an interview." But what has she said elsewhere? What do others in the department—those not likely to go on record—think? Without answers to these questions, a story that is really about a troubling breakdown in the regulatory process is reduced to "Don't Buy These Trucks, They'll Kill You."

When a viewer sees that people are getting killed in trucks, he is going to get angry. He pays taxes to prevent such things from happening. Why do they happen? How can he help prevent them from happening next time? TV news magazines are ill suited to providing the answers, because the answers are not pictures but words. If pictures point to an answer at all, it is a self-serving one: rely on us to alert you to the hidden dangers and the human tragedies that happen when the system breaks down and you can avoid the troubles suffered by unluckier victims. Instead of learning why his government has failed him and others, and how it can be made to work better, the viewer can lean back in his easy chair and say, Thank God for Ca-Chung, and Mike Wallace, and Hugh Downs, and Roger Mudd. Without these fearless ombudsmen, where would I be?

This article originally ran in the August 4, 1986 issue of the magazine.