On November 7, 1969, a week before the huge antiwar moratorium demonstrations, The New York Times ran a full-page advertisement in support of the Nixon administration’s policy in Vietnam. A similar advertisement appeared two days later; and then, on November 15, the Times reported that the pro-Nixon advertisers had blanketed the country with 25 million postcards backing the president, to be signed and returned to the advertisers’ headquarters, The name of the group behind the effort was United We Stand, Inc. Its chairman was H. Ross Perot.

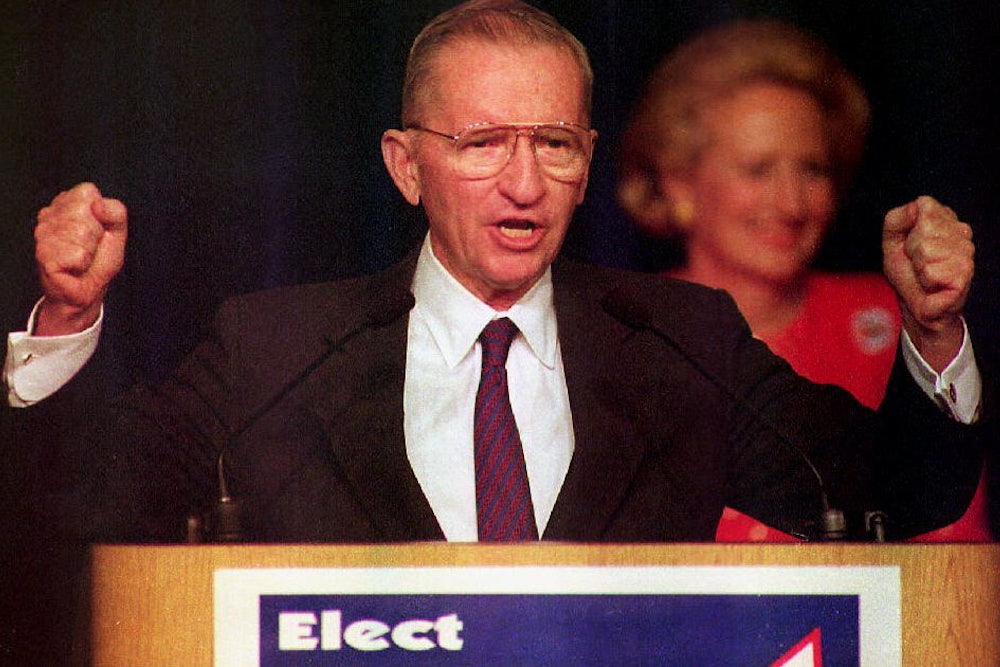

The more that we learn (or in this case, recall) about Perot, the more incredible become his claims that his movement is, as he writes in the first of his two manifestos, “a spontaneous, grass-roots outpouring.” The Times files, along with some remarkable footage from 1970 recently aired on “Nightline,” show that he has been contemplating a political mobilization (complete with plans for electronic town halls) for twenty-five years. Some disgruntled ex-Perot supporters have complained to the press that United We Stand resembles a militaristic political cult. On close inspection, informed critics say, Perot is not the populist that he claims to be. He is, instead, an egomaniac with a clever sales pitch and a fortune to spend.

The startling thing about these discoveries is that they come so late. To be sure, Perot and his advisers did a masterful job of evading public scrutiny during last year’s on-again, off-again media blitz; the costs of having Perot look like a skittish and unserious candidate appear to have been offset by the benefits of having stayed out of the line of fire for much of the campaign. But even when Perot was actively in the race, the coverage of him tended to focus more on his prickly personality and his use of talk shows and “infomercials” than on what he represents in the larger scheme of American politics. Reporters, especially television reporters, rarely delved into Perot’s long political past. More important, most of them seemed unaware that Perot has in fact updated some of the oldest existing currents in our political history. United We Stand’s chief innovation is not its use of technology, but its existence as a tycoon’s political plaything, the first credible national vehicle of its kind independent of the established parties. In other respects, however, Perot is nothing new in American politics. He is one of its clichés.

TO READ PEROT’S programmatic literature is to be reminded of several strains of American politics at once. Perot’s image as an anti-politician, unsullied by pork-barrel grease or backroom cigar smoke, has roots that go back to the earliest days of the republic. As Alan Brinkley has observed, Perot’s fondness for computer gimmickry and for statistics and charts (one-third of his latest book consists of visual aids) recalls the technocrats of the early twentieth century, and the technocratic conceit that even the most stubborn policy problems will yield before scientific, managerially sound solutions.

The boot-camp, can-do spirit that Perot evokes (with debts to his days as a Navy cadet) brings to mind the perennial American fascination with celebrated military commanders, from Andrew Jackson to Dwight Eisenhower, as potential statesmen. (Remember the boom let to replace Dan Quayle with Norman Schwarzkopf on the Republican ticket?) And Perot’s invocation of business standards as a universal yardstick for measuring institutional performance—”in business, people are held accountable”—is pure boilerplate in the land of Henry Ford. Nor is there much that is new in Perot’s ominous corollary, that business corporations and the federal government are basically similar organizations—that, as he puts it, “the United States is the largest and most complex business enterprise in the history of mankind.”

But it is Perot’s populism, his railing against the nation’s political elites and his vaunting of the rest of us, “the owners of this country, THE PEOPLE,” that binds together his disparate political messages and fires up his followers. Since populism often gets portrayed as democracy’s twin, it is easy to get confused about Perot’s place in the populist lineage. Populism, after all, takes its name from the Southern and Western farmers’ revolt of the 1880s and 1890s that led to the rise of the People’s Party—which was a remarkably democratic movement, dedicated to checking the excessive private and political power of monopolies, banks and other monied interests. It was not exactly the sort of movement that Perot has built.

Yet the People’s Party was not immune to certain broader and more troubling habits in American political thinking: a sentimentalization of the virtuous producers; a rendering of history as the product of conspiratorial plots; and an appeal to prejudices about educated Easterners, rich Jews and the usual cast of cosmopolitan villains. Some of the original Populists’ arguments pitted a corrupt and purposeful minority of parasitic outsiders against the people: a simplified view of political realities even in the 1890s. At its crudest, Populist rhetoric reduced the genuine injuries and the real economic grievances of rural life to a melodrama, treating impersonal structural trends in highly personal terms.

Recent historians have argued convincingly that these troubling traits were hardly peculiar to dissident farmers, and that in any event they played a marginal role in galvanizing the original farmers revolt. Without question, however, the melodrama played well enough in the wider political culture to leave the populist impulse open to imitation by a broad range of publicists, crackpots and mere politicians. These less attractive populisms have covered the political landscape so thickly that it has become difficult to remember any other kind.

There has been the curdled populism of frustrated radicals and reformers (beginning with the original Populist-turned-racist Thomas E. Watson) who gravitated, in the face of adversity, toward panaceas, racial theories anti the politics of hate. There has been the calculated populism of large corporations, from the silver miners’ lobby of the 1890s to the flag-waving corporate protectionists of our own time, that plays on public distress, class tensions and nationalist fervor. There has been the personalist populism of political strongmen (Huey Long is the classic case) who have blended demagoguery and substantive reforms with the building of one-man empires.

The last half-century has been particularly rich in American populisms. The Great Depression brought the masquerade-populism of what used to be called the Popular Front, cloaking its Leninism in tributes to The People. In the wake of the New Deal, a distinct right-wing populism, from polemicists such as the 1930s “radio priest” Father Coughlin to today’s Populist Party, has turned the old resentments of monied privilege into attacks on federal bureaucrats, academic experts, secular humanists and liberals in general.

There was a strongly populist cast to much of the white Southern resistance to civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s, which George Wallace carried North with his tirades against “pointy-headed, pseudo-intellectuals,” A different set of populist echoes haunted the Rainbow Coalition and Jesse Jackson’s campaign in 1984, and has emerged more prominently in ghetto street politics as well as in some corners of black academic life. And most powerfully of all, there has been the populism of the Republican Party since the 1960s, a populism that (borrowing from Wallace) has capitalized on white middle- and working-class resentments against liberal social engineers and the black poor while marketing tax cuts for the wealthy as a boon for everyone.

It is a measure of Perot’s political skills, and of the depth of our own political disarray, and of the limitations of the popular knowledge of history, that he has managed to draw upon this legacy and to present himself as the latest man of the people. Perot’s manifestos bristle with the familiar excited rhetoric of “us” versus “them,” delivered as a selfless patriotic call to arms. Instead of the bankers, bureaucrats and welfare queens lambasted by other populists, Perot indicts lobbyists, political action committees and others with special access to power, along with the elected officials who serve them. These people, he charges, have formed “a political nobility that is immune to the people’s will,” a modern equivalent of “the British aristocracy we drove out in our Revolution.”

Perot successfully evades the fact that he has long been one of this aristocracy’s craftier barons. He built his fortune by feeding off the welfare state, using commando-style tactics and insider political influence to secure lucrative contracts from state and federal social service bureaucracies. Little-known investigations by Congress and the General Accounting Office in the early 1970s discovered abundant evidence of strong-arming and profiteering by Perot’s Electronic Data Systems and by its subsidiaries. Rightly fearful of such revelations, and well aware of bow Washington works, Perot and his executives contributed money and manpower to national politicians who were in strong positions to aid EDS.

The company’s first conspicuous Washington connection was to Richard Nixon, and it dated from the late-1960s. It involved, among other things, Perot’s private efforts to rouse Nixon’s “silent majority,” as well as more conventional campaign gifts. (The company, for its part, received protection from a wary Social Security Administration and at least one no-bid contract from the Nixon White House.) Perot and Nixon had a falling out around 1973, reportedly because the president and his men became fed up with fielding Perot’s off-the-wall suggestions. But EDS and its chairman were not parochial in their political loyalties. EDS executives (and Perot personally) also attended to such influential congressmen as Arkansas Democrat Wilbur Mills. In 1974 Perot was the largest private campaign contributor in the country, with the bulk of his largess going to members of Mills’s House Ways and Means Committee and to members of the Senate Finance Committee.

Perot and EDS duly gained from, and handsomely exploited, the kinds of access that Perot now says have ruined the country. In the mid-1970s Perot’s lobbyists (including a former Internal Revenue Service commissioner, Sheldon Cohen) helped friendly representatives and senators draft legislation that, among other things, nearly reaped Perot a $15 million windfall in retroactive capital losses claims. In the late 1970s and 1980s, Perot retained sufficient leverage to win additional agreements, including a no-bid flood insurance contract with the Department of Housing and Urban Development, a contract to process Medicare payments in Illinois and yet another agreement (ultimately aborted) to help administer the U.S. Postal Service.

Meanwhile—and ironically, in view of his alleged business genius—Perot has compiled a calamitous record in the private sector, where his political connections have mattered far less. During the Wall Street crisis of 1970, he heeded the requests of his Nixon administration friends and took over the teetering DuPont Glore Forgan brokerage house, vowing that he would remake the firm in EDS’s combat-ready image, and “do things that other people just talk about.” Four years later DuPont went belly up, a $70 million disaster. When, in 1984, the troubled General Motors Corporation, impressed by EDS’s self-generated mystique, bought the company for $2.5 billion, Perot predicted that he would set the myopic automakers right. But be quickly showed that he lacked either the imagination or the perseverance required for the task, and he jumped ship, covering up his failure with public vituperation against the (admittedly lamentable) GMC management.

How has Perot managed to blur this dubious background? His image is not media-friendly (though he is one of the finest character actors in modern American politics). Nor do his speeches or his writings soar with the emotional oratory that previous populists, beginning with William Jennings Bryan, turned into a kind of American folk art. Perot does have his clever quips, his down-home one-liners (“It’s time to pick up a shovel and clean out the barn!”) and his patriotic kitsch (such as the hackneyed A. M. Willard painting The Spirit of ‘76, featured on the back cover of his new book). For the most part, however, Perot’s presentation, with its flat, at times pinched conversational style and its easy-to-read graphics, conveys all of the liveliness and passion of a Fortune 500 company quarterly report.

No doubt some of Perot’s followers see this flatness as part of Perot’s appeal, proof of his insistence that he is everything most politicians are not. Yet with his plainspoken didacticism, Perot also skillfully plays the old populist role of the village explainer. There have been dozens of such figures in our history, debunkers of the conventional economic wisdom who espouse some simpler and supposedly fairer alternative. Bastard heirs of Tom Paine’s legacy, they have thrived amid the bathos of mainstream politics. When Gertrude Stein invented the term “village explainer,” she had in mind Ezra Pound’s obsessive and tedious discourses on money, credit and politics—the modernist aesthete as homespun windbag. But the classic piece of propaganda in the explainer genre is a now-forgotten, century-old pro-silver tract, Coin’s Financial School by William H. Harvey.

Published in 1894 amid labor unrest, rural revolt and a severe depression, Coin’s Financial School, Harvey’s masterpiece, gained an instant readership of millions and went on to become a chief inspiration for the silver mania that crested during Bryan’s presidential campaign two years later and ultimately split the People’s Party.(One Mississippi congressman reported seeing the work “being sold on every railroad train by the newsboys and at every cigar store.... It is being read by everyone.”) Harvey, a part-time lawyer and a fulltime money crank, believed that a cabal of creditors, politicians and international bankers had tied the American economy to a tight gold standard and was preventing the free coinage of silver that (according to Harvey) would alleviate public distress. Harvey’s views derived from popular currency nostrums that dated back to the Jacksonian era. They also coincided with the positions of the American Bimetallic League, the Western silver miners’ lobby, which, not surprisingly, favored a silver currency and was looking for writers and lecturers to publicize the cause.

Harvey became the league’s star promoter. His great breakthrough, in Coin’s Financial School, was to present the silver panacea in the form of easy-to-understand, cleverly illustrated fictional lectures delivered by Coin—a boyish figure in top hat, tails and knee breeches whom Harvey also dubbed “the little financier.” At the book’s opening, Coin launches into the first of six scheduled lectures on the money question—”a subject that has baffled your fathers,” he says—to an audience of young businessmen in Chicago. It is a dazzling performance, and word soon spreads about the pro-silver lecturer. Annoyed but curious, some of the city’s best-known businessmen, political leaders and university professors decide to attend the remainder of the series, where they raise impertinent questions and try to expose Coin as a fraud. But the intrepid little financier, well-versed in the facts and cool under fire, effortlessly destroys his challengers’ counterarguments and establishes simply and directly the superiority of his doctrine. The men who came to curse stay to bless: bankers, trade unionists, stock brokers and politicians all are “compelled to give assent to [Coin’s] plain and unanswerable views,” united at last against the parasites and their lackeys.

Ross Perot is our little financier. His fixation, to be sure, is with contracting the federal deficit, not inflating the currency. There are some differences between the two in tone. (Although the fictional Coin occasionally flashes irritation at his questioners, his bearing is studiously formal.) But Perot’s translation of economic jargon into everyday language, his insistence that the supposed mysteries of political economy are not really so mysterious (“it’s just that simple”), and his mingling of instruction and political salesmanship into a message of unity are all in the Coin tradition.

Even Perot’s charts (though they are also reminiscent of the pseudo-science that turns up in boardroom presentations and congressional hearings) hark back to “Coin” Harvey, who pioneered the use of arresting graphics as a part of political pamphleteering. Like Coin, Perot sees through the flummery of the politicians and their pretentious apologists and grasps the essential facts of economic life. Spend an hour or so with Ross and he will explain it all, and in words that you can understand. And even if you lack the time or patience to sit through the whole lecture, there is reassurance merely in the impression that he gives of knowing what he is talking about, at a time when many officials and experts seem so uncertain.

On more substantive matters, Perot’s speeches and pamphlets also recall the populist penchant (exemplified by Coin’s Financial School) for finding dark and far-flung plots behind the events of the day. A century ago, when Harvey was writing, populists had a weakness for describing the ultimate foe as a conspiracy of British bankers with Jewish names who were aiming to destroy the United States by demonetizing its silver. (Coin’s Financial School is anti-British, but it is not anti-Semitic; Harvey bared his garden-variety Judeophobia in one of his other tracts, A Tale of Two Nations, also published in 1894.) With bribery and other subterfuges, the banker cabal had supposedly wormed its way into American politics and pushed through legislation that served its grand design.

Perot is more concerned with the Japanese than he is with the Jews, and his observations, at least when he presents them publicly, are far less crude than Harvey’s. Once in a while, he even stops to remind his readers that the Japanese, along With our other major trade competitors, are our allies, not our enemies. But elsewhere he plays some of the old chords, harping on how the unrelenting Japanese (sometimes he throws in the Germans and the Arabs too) are bent on thrashing America in a business war that is every bit as serious as World War II or the cold war was. And he really hits a nerve when he purports to explain Japanese success and American decline as the result of a systematic “betrayal by the elites”:

If you wonder why international trade is not played on a level playing field, don’t point a finger at the Japanese or the British or anyone else. Look first at our own political elites who enter government to gain expertise and personal contacts while on the public payroll, then leave to enrich themselves by taking inside knowledge to the other side....What has happened to common decency, ethics and patriotism among the people who are supposed to lead our country?

In his latest tract, Not For Sale at Any Price, Perot tells his readers that the one thing he hopes they will remember are his warnings about these turncoats, especially the lobbyists for foreign countries, the “AWOL soldiers who turned up fighting for the enemy.” Their treachery, he asserts, “is the reason that 2 million high-paying factory jobs were shipped to Asia during the 1980s.” In case anyone misses the point of this stab-in-the-back theory, Perot, breaking from his matter-of-fact delivery, begins to shout, “THIS IS ECONOMIC TREASON”—and therein, supposedly, lies the key to understanding the United States’ fall from economic supremacy.

Beneath this familiar populist scenario lurks a more generalized appeal to provincial prejudices. In Coin’s Financial School, the little financier runs intellectual circles around learned academics and pampered businessmen. His success is the stun of his charm. Perot turns out to be an old hand at trying this sort of thing, baiting his foes as effete obscurantists. More than twenty years ago, when Daniel Patrick Moynihan (then a Nixon adviser) got a tepid response in a speech before the U. S. Chamber of Commerce, Perot set the same crowd roaring with some pointed remarks on why businessmen were better equipped than social scientists to solve the nation’s problems. Some years later, during his ill-fated stint with DuPont Glore Forgan. Perot openly remarked that Wall Street’s problems stemmed from the brokers’ lack of virility. (“I don’t know whether to kiss him or shake his hand,” was a typical Perotism about a Wall Street executive.) These days Perot has learned to clean up his act, hut he expresses some of the same impertinence in his contemptuous jousting with the mainstream press (“Is that the way we’re going to play the game?”), which is the country’s pre-eminent elitist clerisy in the modern populist imagination.

PEROT’S POSTURING would probably count for little, however, if he stopped there. Like “Coin” Harvey and other successful populists, Perot also has his finger on genuine problems that beset the country, and he knows exactly how to exploit them. Far more than most leading Democrats and Republicans. Perot has a feel for how millions of ordinary people actually experience life in contemporary America, and he expresses that understanding keenly.

Part of that understanding has to do with politics. In truth, Perot is the furthest thing from a democratic leader. By numerous accounts, he runs United We Stand much as he has run his companies, as a closely guarded autocracy staffed by like-minded people subject to a clearly defined chain of command. (“I’m used to being able to say something once, in a whisper, and having committed guys across this country go make it happen,” Perot once boasted to a reporter.) Perot’s vision of a streamlined, businesslike political order, his pseudo-plebiscitary electronic town halls (which would actually resemble a cross between televised political shareholders meetings and the old game show “Let’s Make a Deal”), his hostility toward Congress and the press, his impatience with slow-footed democratic procedures, all amount to a repudiation of the checks and balances that are the soul of American government. And without question this side of Perot excites an authoritarian anti-democratic streak among some voters fed up with politics as usual. Their sentiments were summed up in last year’s bumper sticker, “Ross for Boss.”

Still, if Perot is no democrat, he does play on a deep popular anger at existing undemocratic abuses, and also on a persisting urge for purposeful political involvement. Perot’s attacks on Washington influence-peddling may reek of hypocrisy and opportunism, but there is no denying that PACS, lobbyists and big-time special interests exert inordinate power at the public’s expense. And in seizing on the widespread disgust at how smugly Washington conducts its business, Perot fills his program with appeals to the better angels of our nature, to “take personal responsibility for our actions and the actions of our government,” to get involved and make a difference. His much-heralded volunteers may lack credible power within his organization, but Perot manipulates them into feeling as if they are changing the world as they go around ringing doorbells and handing out campaign flyers. For many Perot loyalists, it is as close as they have ever come to democratic participation in a presidential election.

Perot similarly understands the mounting public frustration at how the social issues, especially abortion, have tended to dominate the economic issues that many consider the federal government’s primary responsibility. There is a fascinating ambiguity to Perot in this regard. As a businessman, Perot is famous for his enforcement of a no-nonsense morality. From at least the 1970s on, he had his male employees follow strict codes of conduct and personal appearance: no over-the-collar hairstyles, no beards, no marital infidelities. There has never been much question about where his organizations have stood in the culture wars.

But as a politician, Perot often comes across as a libertarian, taking a forthright pro-choice position (including support for federal funding of abortions for poor women) while urging what he calls “a national compromise on abortion,” firm in his belief that “the people are ready and willing to put [past] divisions behind us.” With apparent sincerity, he denounces both major parties for their racial posturing (though his lack of experience and knowledge in this area showed up last year, as in his blooper about “you people” to the NAACP). Only on the issue of gay rights has he been incapable of getting his lines down, wavering between support for the discriminatory status quo and half-hearted reappraisal.

PEROT HAS ALSO become increasingly sensitive to the legacy of Reaganomics and how its effects are understood by a large portion of the electorate. Early in last year’s campaign, Perot handled the topic gingerly, deriding the explosion of the federal debt while making only vague references to “trickle down economics.” He seemed especially wary of criticizing Reagan directly, lest he alienate those who, despite everything, still adore the man. In United We Stand, his campaign tract of 1992, Perot even excused Reagan’s deficits at one point, on the grounds that they helped to bankrupt the Soviet Union. Currently, however, Perot (while still refraining from criticizing Reagan personally) portrays the Reagan-Bush economic policies as a thoroughgoing assault on the jobs and incomes of the broadly defined middle class.

No Democrat, in fact, has done a more effective job than Perot in toting up the devastation: rising unemployment; corporate jobs lost; the manufacturing base depleted; real wages cut, income inequalities up; tax burdens shifted downward; junk bond and S&L scandals galore. “A disturbing trend has emerged from the decade of greed, the era of trickle-down economics and the period of capital gains tax manipulation,” Perot writes; “We are headed for a two-class society.” Reading these lines you can practically hear the shouts of approval from workers in the Rust Belt along with “downsized” middle managers, hard-pressed wage-earning couples and (here and there) some left and liberal intellectuals. The cheering swells when Perot outlines the rough terms of a national industrial policy and calls for billions more in federal spending on infrastructure, aid to cities and public education. It becomes deafening when he attacks the North American Free Trade Agreement.

AS PEROT FULLY elaborates his program, however, he gets the attention of another group of people, composed largely of traditional Republicans: the deficit cutters. Perot has received considerable credit from critics of the deficit for dramatizing the issue, and for forcing politicians and voters alike to face up to the hard realities of a $4 trillion debt. Even longtime liberals can see that the Reagan and Bush administrations succeeded all too well in their fiscal revolution, while placing an enormous burden on future policy-makers. Yet among the flocks of deficit hawks, Perot stands out like an unpiloted B-52. He would not simply reduce the annual federal deficit, he would eliminate it within five years. Not since the heyday of Barry Goldwater (or Robert A. Taft) has any national political figure turned back to bedrock pre-Keynesian economics to such a degree. (The Reaganites, of course, always talked piously about balanced budgets, but supply-ride policies led rapidly in the other direction.) The government, Perot says, must learn to balance its accounts just as “in your family, when you can’t pay the bills, you either get a raise or start cutting back to the necessities”—and the burghers of Main Street, the upholders of what used to be Republican orthodoxy, exult.

Although Perot claims otherwise, it is difficult to see how driving down the deficit so drastically and so quickly could avoid squelching the fragile signs that the economy may be in recovery. And were this to happen, the people hit hardest by rising unemployment and regressive taxes would include those very struggling working families whom Perot says he wants to protect. That possibility never dawns, of course, in Perot’s literature. Instead Perot sticks to the broader theme of sacrifice, which for the moment has caught his loyalists’ imaginations. And as long as it does, the plan has several political advantages. As ever, the message is simple: balance the budget, and soon. And by combining middle- and working-class outrage with his draconian deficit remedy, he puts himself in a position where he can shift his ground quickly and attack whomever he pleases, as political circumstances dictate.

Recent events illustrate how this self-serving strategy operates. A check of Perot’s fiscal proposals shows various broad similarities to the proposals that have come from the White House: increases in discretionary spending on infrastructure, urban aid anti education a hike in the marginal rate of income taxes for individuals in the top income brackets, in Clinton’s case above $115,000, in Perot’s somewhat more regressive plan $55,500. For fiscal year 1994, Perot’s plan calls for a net reduction of $12.8 billion in defense, discretionary and entitlement spending and a net rise of $34.5 billion in new taxes, a ratio of about $2.70 in new taxes to every dollar in spending cuts. So where has Perot been while the Republicans killed Clinton’s modest stimulus bill and vowed to kill Clinton’s new taxes? He has been heckling the president, hobnobbing with House Republicans and coyly sidling up to no-tax Republican Senate candidates.

HOW LONG CAN Perot continue in this politically irresponsible way? How much influence will he have over the policy debates? This is hard to predict. But the real significance of Perot’s rise has less to do with the state of policy and more to do with the state of politics. Here, after all, is a man who has roamed the political landscape for a quarter century, searching for business deals, clout and a mass movement to lead, certain in his own mind that he, the billionaire businessman, has some unique talent to lend to the country. In 1992 he finally found his movement, even if he would like to pretend that the movement found him.

It could well be, as various writers have argued, that Perot’s success is a signal that we have entered into one of those massive political realignments in party allegiance that mark off one era in our political history from another. Once, in the 1850s, such realignment led to the death of a major party, the Whigs, and the birth of a new one, the Republicans, which eventually paved the way for the Civil War. Other realignments in the 1890s, 1930s and 1950s have had less revolutionary but nonetheless profound consequences for the shape of national political life, as voters shifted in large numbers from one party to another, creating new grand coalitions. Always these realignments have announced themselves through the effort of some third-party or schism—the Know-Nothings, the People’s Party, Robert LaFollette Jr.’s Progressive Party, George Wallace’s American Independent Party—that serves as a temporary vehicle for voter discontent until the new party coalitions take shape. Perot’s movement, though hardly a conventional third party, may be in this respect, as in much else, performing a familiar historical role, foreshadowing a recomposed party system whose shapes are still unclear.

More disquieting is what Perotism discloses about the condition of political democracy in the United States. Money, to be sure, has long been the mother’s milk of politics, and no one should imagine that there has ever been an idyllic American democratic era. Still, there is an enormous gap between the kind of political agitation that preceded the rise of the Republican Party or the People’s Party and the one-man show of Ross Perot. Thirty years of purposeful political labor by abolitionists, free milers and others lay behind the political crises of the 1850s; the People’s Party flowered from nearly as many years of rural cooperative-building and protest politics.

Now, however, thanks to many of the trends that Perot deplores—above all the forbidding costs of running a national media campaign—it has become possible for a wealthy individual to bypass that process entirely, construct a sort of Disneyland democracy and pseudo-party, and present himself as the people’s voice. Small bands of left-liberals and social democrats (with tides such as the New Party and Labor Party Advocates) have recently begun trying to organize the kind of national democratic organizations that Perot’s group pretends to be. But even the most sanguine of them acknowledge that, given the situation, the job could take twenty years or more—steady work, but not the sort of thing that will sate the populist fury.

PEROT’S SUCCESS, in other words, marks the magnitude of the distance that has grown up between populism and democracy, and indicates the shabbiness of modern populist politics. Populism has devolved, finally, from a set of political ideas into a posture of angry defiance. It is now preeminently a mood, a surly mood of defeat and powerlessness, a raging distrust of established institutions—indeed, at times, of power itself—linked to a nostalgia for a supposedly simpler past. Because it is a mood, it has no specific location on the political spectrum: the New Left created its own populist conceits just as surely as the New Right has. And because it is a mood, it is a singularly effective tool for politicians who would build their careers out of the accumulated social injuries of an uncertain time.

For the past twenty years, the Republicans have proved peculiarly adept (and the Democrats peculiarly hapless) at catering to the populist mood. George Bush’s pork rinds were the least of it: much more powerful was the Republicans’ ability to make their party—which is, in truth, an utterly modern party of business—look like a bastion of anti-modernism, led by crusading restorationists of morality and rugged individualism, opposed to the exotic “them”—the sex perverts, the criminal lobby, the “Harvard-boutique liberals.” The Democrats, miserable marketeers who were unsure of their message (some of whom share responsibility for the tax-cut deficits and scandals of the 1980s), occasionally tried to counterattack with an anti-business populism of their own, but always without much conviction and with even less skill.

In 1992 the Republicans paid for their pandering, and the price included Perot. After twelve years in office, they had moved the country not one inch closer to the and-modern restoration and showed little evidence (beyond lip service) that they seriously intended to do so. The result was the disastrous convention in Houston, which delivered Republican populism to the right-wing extreme. History, too, played its tricks on Republican populism, as communism’s fall robbed it of important ideological glue and as the costs of Reaganomics began to mount. Enter (and then exit and then re-enter) Perot, shifting the populist appeal to the politics of rich and poor, talking of new betrayals and plots, .joining the wounds of class to traditional Republican economics, in a movement totally beholden (whatever his obfuscations) to him and him alone.

One of Perot’s constant points is that even the best of intentions get crushed in the Washington world of connections and power peddling. “Take any good, decent citizen,” he writes, and give him enough perks, privilege and access, “and he’ll lose touch with reality.” Like much else about the supposedly “new phenomenon” of Perot, this theme is an old one: power corrupts (although Perot never tells how his good intentions somehow survived intact). But if power corrupts, so does powerlessness, or more precisely the feeling of powerlessness. And one name for that corruption is Ross Perot.

This article originally ran in the August 9, 1993 issue of the magazine.