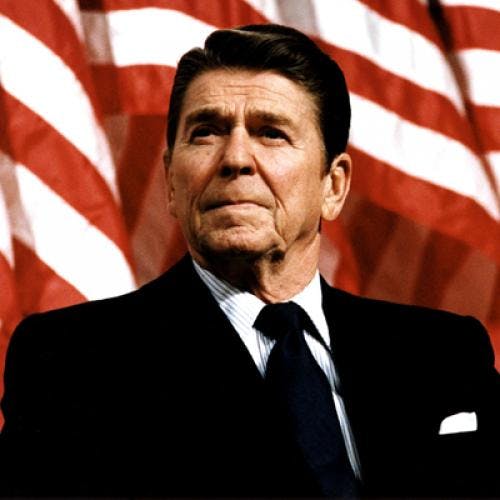

The big oil companies finally have a friend in the White House. Ronald Reagan has already sped decontrol of crude oil prices and set the wheels in motion for a new natural as deregulation effort. A president who genuinely believes that pro-industry policies will cure the nation’s energy ills comes as a welcome relief to the industry after four years of Jimmy Carter’s strident assaults. But both Reagan and big oil should bear in mind that their cozy relationship is full of political peril. For the president there is the danger of guilt by too close association with the most spectacularly unpopular industry in America. For the big oil companies there is the danger of an even bigger public backlash if they fail to meet Reagan’s goal: a relatively painless energy fix.

The president’s friendliness toward the industry is nothing if not gutsy. Since the 1973 Arab oil embargo, when energy prices began their rapid climb, polls have ranked big oil in the nether reaches of public popularity. Paul Bloom, the Carter lawyer who made a splash by giving away to charity three million dollars in recovered oil overcharges, puts it this way: “The American people, broadly speaking, prefer the Black Death to the major oil companies.” Coming from an old regulator like Bloom, such sentiments are unlikely to impress the Reagan White House. But they are shared by James McClure, the Idaho Republican who chairs the Senate Energy Committee. “The only way you can avoid political danger is by cussing the oil companies every hour on the hour,” says McCIure, who’s hardly a critic of the industry. “Being close to them isn’t at all a comfortable place to be.”

McCLURE speaks from experience. Early this year, soon after Reagan decontrolled oil, the senator wrote to the chief executives of the 15 largest oil companies. Decontrol had released the companies from longstanding allocation-of-supply regulations, and McCIure appealed to them not to use their newfound freedom to make sudden withdrawals from marketing areas that would disrupt supply patterns. Otherwise, he warned, there might be growing pressures to reimpose regulations. But almost immediately three major companies announced they were cutting off sales to hundreds of retailers.

The administration holds such inconveniences to be an unfortunate but necessary side effect of the effort to make America energy-independent. Remove the constraints, the president says, and the industry will lead us back to strength and self-sufficiency. According to Reagan’s oilman friend Michel Halbouty, it will “produce, produce, produce” the energy the nation needs.

The administration has lost no time turning that belief into action. It has retained and magnified the Carter administration policies that used price as a weapon to bludgeon the nation into using less fuel. At the same time, through budget cuts and policy shifts, Reagan has banished Carter programs (like weatherization assistance) that were designed to cushion the effects of high prices on the lower and middle classes or (like the energy-efficiency standards for buildings and appliances) to mandate conservation. Under the Reagan administration the energy situation is deemed to be a symptom of the nation’s economic problem, not a cause of it. Soon after his appointment as energy secretary, James Edwards loudly proclaimed that government spending was “the only cause” of inflation.

The more time he has spent on energy, the fewer such comments he has made. But he and the White House continue to regard higher prices and fewer regulations as the only energy policy the country needs. The administration’s policies haven’t aroused much public outcry yet. Reagan’s embrace of the industry fortuitously has coincided with a world oil glut, as Saudi Arabia floods the market with its lower-priced crude in an effort to reassert its dominance over its maverick OPEC brethren. The real risk for Reagan will come when the Saudis get what they want from OPEC and start closing the spigot. If they cut back production to their official 8.5 million barrel-a-day “ceiling” from the current output of 10.3 million barrels, will the president still be able to count on his friends from big oil?

The problem is that oil companies are economic rather than political beasts, ultimately responsible to their shareholders, not to any government. As such, they possess a nearly boundless capacity to embarrass even a friendly regime by reacting to situations as profit-making entities rather than as instruments of public policy.

The recent spate of multi-billion-dollar oil-company takeover bids for mineral and mining concerns has prompted remarkably little response in Washington so far. But some observers—even some friends of both the industry and the administration—see danger signals ahead. They say that by using oil profits to diversify into other businesses, the industry is undercutting its own arguments, and those of its White House ally, that higher prices will buy more energy production.

Recently a senior executive of Sohio, glowing at the prospect of snaring Kennecott Corporation for $1.8 billion, came to Washington to visit a few movers and shakers. He got a rude lesson in practical politics from an important Senate Republican staffer. “I told him,”the disgusted staffer recalls, “I think you’ve just about destroyed any possibility for changes in the windfall profits tax and you’ve made things much more difficult on natural-gas deregulation!” The aide, who like the administration favors these items, says that such diversification “makes sense from a financial standpoint, but it’s politically stupid.”

THE WHITE HOUSE also had a lesson in oil industry self-interest following Reagan’s decontrol announcement. After doing their best to downplay the possible effects on gasoline prices, Reagan officials had to stand by red-faced while the industry rushed to raise prices more in the first few days than the administration had predicted it would over a period of months. “I was somewhat surprised,” said energy secretary Edwards, who as front-man for the announcement had the reddest face of all. “Some of the oil companies may have used this [decontrol] as an excuse,” he suggested, to sneak in other price hikes as well.

Still, these occasional alarms haven’t kept the administration from continuing to dispense goodies to the industry. Most recently, in the guise of budget cutting, the Department of Energy cut back funds for lawsuits against oil companies that overcharge. These lawsuits date from the period when prices were still controlled. Department enforcement officials say quietly that the 80 percent spending cut proposed would all but cripple their ability to prosecute those cases. Paul Bloom filed many of those suits and believes that Reagan’s policies someday will return to haunt him. “The administration that appears to be the handmaiden or errand-boy of the industry,” he says, “is necessarily going to be seen as ignoble and contrary to the public interest,” Robert Teeter, the Republican pollster who played an important role in the Reagan-Bush campaign last fall, says that day may never

arrive. But Reagan will avoid it. Teeter says, only if he can continue to place his pro-industry moves in the context of a broader economic package. “If things get suddenly worse”—if, for instance, the Middle East erupts again and disrupts US oil imports—then Reagan may be in big trouble. In that case, Reagan’s record of industry accommodation could become a handy target for political missiles. In any case, whether or not the shortage occurs, the public will expect to see the improvements promised by the administration and the industry.

It’s just that question of expectations that leaves big oil a little uneasy at finally being invited in from the political cold. No company will refuse favors bestowed by the administration, yet there’s concern about Reagan’s tone, which resembles the upbeat, we-can-produce-lots-more rhetoric of the independent wildcatters more than it does the cautious forecasts of industry giants like Exxon. One big oil lobbyist says, “. . . sometime in the future, we’re going to have to be saying that we have more energy than we would have had. But no one can say we’ll have enough. . . . Just because tbe president tells tbe American people nice things about the oil companies, it doesn’t mean they like us any more,” So if things go wrong with the rosy picture of energy independence Reagan likes to paint, he says, “there’s no place for us to hide.”

Rich Jaroslovsky is a Washington correspondent who covers energy. This article appeared in the May 2, 1981, issue of the magazine.