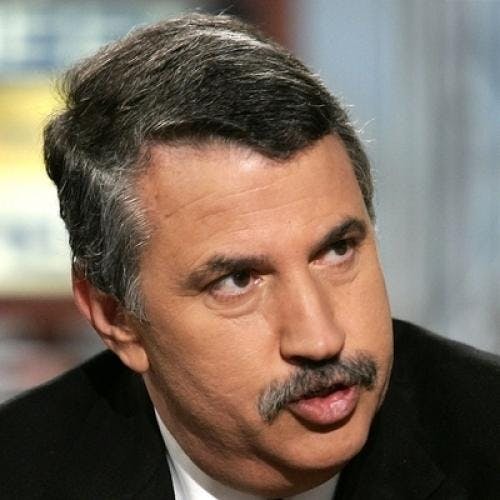

From Beirut to Jerusalem

By Thomas L. Friedman

(Farrar, Straus, and Giroux 525 pp., $22.95)

Thomas Friedman’s account of his journey as a reporter from Beirut to Jerusalem is rich in precisely the qualities that made his dispatches from those two capitals so memorable, and so breathtaking. We have to go back to David Halberstam, and perhaps to Homer Bigart, for another American foreign correspondent so unerringly alert to the illuminating detail. Most of Friedman’s colleagues cover the area as a police brutality story, as a morality play with victims and victimizers, or as a tale of insufficient diplomatic pressure on wanton Israelis. Those are the permissible styles of Middle East reporting. But the historical and psychological complexities of the region are better served by Friedman’s vivid, even intimate prose.

Friedman’s longtime readers know what those who have depended for their knowledge of the Middle East on other, less imitated do not: that the heavily placarded walls of this regional house of passions are not its inner courtyard. Friedman penetrates these walls, into spheres that the local inhabitants would prefer to have sealed to outsiders. At its best, Friedman’s journalism does what we have come to expect from the rare pieces of genuinely affecting pieces of fiction set in the Jewish-Arab vortex; he shows us the distinctive intensity and the distinctive abandon by which those people live.

But, Friedman’s book is fatally lacking in a careful, consistent argument. The closest thing seems to be his insistence on equivalence, his view that Israel and Lebanon are not only in the same neighborhood but of it. He guides us deftly through two polities with different origins and different destinies, but his retrospective reflections show an appealing and misleading symmetry. Friedman spent the last decade in the Middle East, five years in Beirut, five years in Jerusalem; roughly half of his account is given to his locales. The very structure of the book bespeaks equivalence; but the equivalence turns out to be more than biographical.

The most compelling portions of Friedman’s book are about the torment and the turbulence that is Lebanon. There is a freshness to his chronicle of Beirut that is missing from his Jerusalem chapters. This can be explained, I suspect, by his combination of physical closeness and psychological distance. Friedman had no personal stake in what he would find in Lebanon. It was not likely to exhilarate him, but neither could it disenchant him. His curiosity led him where it would. He had nothing to prove to himself, or others, except that he was good at what he was doing. He came with some Arabic, a distinguishing possession (his guild, at least its American membership, puts little value on native tongues.)

Naturally, he saw most of the pertinent powerful, but Friedman’s reports paid extraordinary attention to common folk. In a society as disorderly as Lebanon, the mighty rarely speak with authority. In fact, none of the usual paradigms and models hold in Lebanon. Friedman understood this. He was not tugged to the profound. Sure, beneath the flimsy surface of the Lebanese state, there is a class dimension to the chaos; and there are intersectarian tensions, between clan and clan, and, oh yes, ethnic divisions (as opposed simply to confessional ones), clientalistic structures, foreign intruders, and uneven economic development. But Friedman, giving each of these its due, does not allow such graduate student themes to divert him from the actual plot.

The plot may lack reason, but it has structure. (And its villain, as Friedman clearly shows, is not Israel.) What propels Lebanon, its underlying truth, is the momentum of the feud. The reality of the feud, or more accurately, of the scores of feuds, cries out from Friedman’s pages. This is a country where people would be foolhardy to expect to die in their own beds.

Friedman ponders whether he’s been to Hobbes’s state of nature. It is a pointless conceptual diversion. Where he has been is a place whose political culture includes casual butchery among its norms. At this very moment, for example, the Palestinian relatives of the victims of Sabra and Shatila are in the arms of the forces responsible for their murder. In Friedman’s own apartment building, 19 innocent people were blown up in a squabble between PLO bands over the ownership of a flat. Syrians and Maronites, Muslims and other Muslims, are still killing each other. Life is cheap in Beirut, very cheap. Still, in some moving passages, Friedman evokes the redeeming remnants of Lebanese society, those who confirm, against all the suffering, that the old Russian anarchists were right to think that there is a human instinct of mutual aid. There were many times during the last 15 years when Lebanon displayed the impulse to help and to solace, when many people did not withdraw into sullenness. And there were once good times in Lebanon, before politics became a continuation of gangsterism by other means. But to leave it at that would be to idealize the past, to ignore what Fouad Ajami has called “the fury that lurked underneath the tranquility and the pretensions.”

Friedman chastises the invading Israelis of 1982 for not grasping the Shiites as a factor in the Lebanese future. No doubt the Israeli invasion did awaken and provoke the Shiites (as Friedman notes, the largest group in the country). But the story is a bit more complicated: there was a debate in Israeli intelligence and military circles over whether they should tilt toward the Maronites or toward the Shiites, as if tilting were a self-evidently fruitful enterprise in the first place. They chose the Christians, a fateful, fatal choice. Friedman’s insistence that the Israelis failed to recognize the fury of the Shiites might lead you to think that he did grasp it; but he didn’t, and in a way he still doesn’t.

Immediately following his complaint about the blindness of the Israelis, he betrays nearly the same blindness. “The real Lebanon was two Lebanons,” he writes, “…Christian and Muslim.” Oh, so that’s how the country is divided, is it? Friedman seems to think that since the Shiites are Muslims like the Sunnis (and most of the Palestinians), they share the same interests and aspirations. Quite the contrary. It is true that the Shiites have differences with the Maronites, differences they share with the Sunnis; they were certainly not prepared to see the Israelis bolster the faltering sway of Lebanon’s Christians. But their deeper quarrels—historical, theological, existential—are with the Sunnis, and especially the Sunni urban elites, who were always ready to carve up dominion over other Lebanese with the Maronites, and how had humiliated the Shiites for centuries. Not one of the Shiite prophets and tribunes make more than a cameo appearance in Friedman’s text.

The Shiites also nursed a grievance against the Palestinians, who had rolled over the Shiite heartland south of Beirut and made it the staging ground for the war of liberation against Israel. Sprinkled through Friedman’s book are a few skittish references to that reality, subsumed under the shorthand “Palestinian mini-state,” a phrase that pleads for an elucidation that Friedman fails to give it. It was this reality that accounted for the rice-and-flowers reception accorded the Israelis by the Shiites of the south in the early summer of 1982. (Friedman tells us that even West Beirut Muslims, presumably including Sunnis, “welcomed the Christian-led Lebanese army when it came in and replaced the PLO.” But why? What did this say about Palestinian rule?) Doubtless the memory of the “Palestinian mini-state” is also what lies behind the on-again, off-again war of the camps waged between Amal, the mainstream Shiite militia (also unmentioned) and the various winglets of the PLO.

Friedman says of his colleagues what he might have said of himself, that “the overfocusing by reporters on the PLO and its perception of events led them to ignore the Lebanese Shiites and their simmering wrath at the Palestinians for turning their villages in south Lebanon into battlefields.” Overfocusing, indeed: Friedman tells us a bit about what the PLO mini-state in Lebanon did to the PLO, but unrevealingly little about what it did to the Lebanese. It was not something he wrote about at all prior to 1982. Even now, his generally tough prose weakens when he writes about the Palestinians.

With almost al the other Western journalists then resident in Lebanon, Friedman shares the common coyness about the one concrete example anybody has ever experienced of direct PLO rule. Still, in some devastating passages, he settles once and for all the debate over whether the Western media in Lebanon flacked for the PLO. Friedman, who won many confidence-building battle stripes for having displeased the Israelis, describes how Arafat and his legions met “a huge generally uncritical international press corps, many of whose members identified with the PLO as underdogs and ‘60s-style revolutionaries.”

In Beirut each faction had its own territory, its own enforcers, its own version of reality. Friedman recalls that rarely could a reporters have the satisfaction of feelings that he has really got to the bottom of something. Some simply improvised. However they coped, it was in an atmosphere of intimidation. “There was not a single reporter in West Beirut who did not feel intimidated…no one had any illusions that [the factions] would tolerate much serious reporting.” After fellow Timesman Bill Farrell told him that Arafat’s personal spokesmen complained about the insufficient friendliness of Friedman’s filings on the PLO, he “law awake in my bed the whole night worrying that someone was going to burst in and blow my brains all over the wall.” The next day the spokesman told Friedman that he wanted him “to do a little better in the future.” It’s the kind of suggestion that concentrates the mind.

Friedman implies the intimidation came from all sides, but if any reporters especially feared the Phalange, it didn’t show in what they wrote. Rather the opposite: Friedman admits that “the truth is, the Western press coddled the PLO and never judged it with anywhere near the scrutiny that it judged Israeli, Phalangist, or American behavior.” Indeed, to enforce a certain minimum discipline all the Palestinians had to do was manage their leaks efficiently. “For any Beirut-based correspondent, the name of the game was keeping on good terms with the PLO, because without it,” Friedman concedes, “you would not get the interview with Arafat you wanted when your foreign editor came to town.” That is quite an admission.

Having levels such serious allegations, however, Friedman is suddenly struck dumb. He names the transgressions, but the transgressors. This is an odd note of reticence in an outspoken book. It is more proof of the press corps’ arrogant insistence that it be treated as some sort of secret fraternity, insulated from outside examination and criticism. Friedman may be the first mainstream journalist to acknowledge what has been obvious about the coverage of the Middle East for years, but he wants to have it both ways: he wants to tell the truth, but not too much of it. He certainly doesn’t want to give him comrades reasons to stop thinking of him as a blood brother.

Friedman understands that the pro-PLO, anti-Israel bias is not limited to the reporters on the ground, or at least he understood that as of March 22, 1988. On that day, breakfasting in a London hotel, he noticed that the editors of The International Herald Tribune had given its front-page photograph to “an Israeli soldier not beating, not killing, but grabbing a Palestinian” while paying much less attention to genuine atrocities elsewhere, not least in the world of Islam. This was a “lack of proportion” that he would begin to notice in other media. (Perhaps he hadn’t noticed how in the early days of the war in 1982 how complacently reporters and editors endorsed invented numbers for casualties.)

The feelings of a reporter or an editor about the PLO cannot be isolated from his views about Israel. Friedman draws a distinction between European and American journalists. The European correspondents, he says, need a ruthless Israel in order to “absolve themselves of some of their own guilt” for what happened to the Jews before and during World War II. “Look,” Friedman has these correspondents saying, “the Nazis were not unique…” The Americans, he assures his readers, are morally less callous, are not hostile towards Israel in the European manner. Their prejudices are the consequence of something altogether more elevating. Because they hope that Israel “will one day fulfill its promise,” against which they indefatigably measure it, American correspondents “seem to relish Israel’s misdeeds.”

Friedman argues that these reporters’ (and other Americans’) “identification with the dreams of biblical Israel and mythic Jerusalem run so deep…that when Israel succeeds and lives up to its prophetic expectations…[it] is their success” too. (He adduces Woody Allen as an authority on the “death” of the Israeli “dream”!) He follows this explanation with a random romp through the historiography of biblical symbolism in America, from the Puritans to Martin Luther King. This is all too profound. The American press corps is not made up of unrequited lovers of Zion. But Friedman himself is a perfect illustration of the idealistic goofiness that he wrongly imputes to his colleagues.

From Beirut to Jerusalem is a personal melodrama. Its author portrays himself as a crushed Jewish romantic. For his high school years were “one big celebration of Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War … I was insufferable.” The appraisal seems fair. Friedman’s portrait of himself as a young Zionist might have been the work of a Phillip Roth imitator. Friedman even provides the confession that since the age of 15 he had “never really been interested in anything else” but Israel (and, he now tactfully adds, the Middle East). If that is true, he should have disqualified himself from his beat.

His Zionist bewitchments, certainly, didn’t prevent him from telling the Arab side of the story. He bend over backward to be fair to the PLO. We have his own testimony that he, like his colleagues, coddled the PLO. Nor did his Zionism prevent him from giving the Israeli side. What cannot be denied, though, is the he deals with his own people—and they are, without embarrassment, his own people—far more harshly than he does with their enemies. Menachem Begin doesn’t come of anywhere as well in this book as does Yasir Arafat, who is a “teflon guerrilla,” and later on the “gipper,” and later like a rock star. This, again, is the logic of equivalence: Israel is lowered a bit, its enemies are raised some, and they meet in the same ugly place.

Friedman won a Pulitzer Prize for his reconstruction of the Sabra and Shatila massacre. (He shared the prize with Loren Jenkins of The Washington Post, whose version of events was rather different.) He was psychologically enmeshed in his story. “One part of me wanted to nail Begin and Sharon—to prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that their arms had been involved in a massacre in Beirut in the hope that this would get rid of them…Yet, another part of me was looking for alibis—something that would prove Begin and Sharon innocent, something that would prove the Israelis couldn’t have known what was happening.” By the time he interviewed the Israeli commander in Lebanon, Gen. Amit Dron, Friedman was beside himself with rage:

I banged the table with my fist and shouted and Dron. How could you do this? How could you not see? How could you not know? But what I was really saying, in a very selfish way, was, “How could you do this to me, you bastards? I always thought you were different. I always thought we were different. I’m the only Jew in West Beirut. What do I tell people now? What do I tell myself?”

The next morning a still petulant Friedman “buried Amit Dron on the front page of the New York Times, and along with him every illusion I ever held about the Jewish satte.”

General Dron deserved punishment. But is it true that Israel was hostage, during all his years in the Middle East and in his book, to Friedman’s illusions? Friedman think that his passions “made me a better reporter.” He makes no bones about what there were. As a boy, Israel made him proud, stiffened his spine, filled him with a tribal feeling. Like most tribalists, he thought his tribe was perfect. It wasn’t until he went to Israel in the 1980s, he says in a startling confession of naïveté and ignorance, that he “discovers that it isn’t the Jewish summer camp of his youth.” His discovery simply busted his Zionist heart. I was myself a passionate child Zionist, too, but I knew very few others whose Israel was so unrealistic, so unerring, so unflawed, as Friedman’s. Those I did know grew up.

When Israel failed Friedman, in short, Israel failed. Now, there is something attractive about the position of the critic, but Friedman is not professionally a critic, he is professionally a reporter. And the silly standard by which he measures Israel should not be held up to any society. He certainly does not hold the standard up to Arab societies. In fact, he seems to hold Arab societies to no standard at all.

Friedman’s expectations of Israel are justified, he seems to believe, by his Jewishness. His book includes some meditations about a religious vision for the Jewish state, a dangerous subject about which he appears to know little. More concretely, he writes that “what the West expected from the Jews of the past, it expects from Israel today.” He may be right, but not quite in the way he intends. For what the West expected from the Jews of the past was that they be docile and cowardly and craven. For many centuries in many places the Jews fulfilled those expectations. Zionism was meant to put an end to such fulfillments, and to propose others. The Hebrew poet Uri Zvi Greenberg asks, Where are there instances of catastrophe / like this that we have suffered at their hands? / There are none—no other instances. / This is the horrifying phrase: no other instances.” Given this history, it is grotesque to invoke the West’s expectation of the Jews as a standard for their state. Bur Friedman turns the screw still one more time. “After all the centuries of being lectured by the Jews,” he says, the West finally wants to see whether these same Jews will live up not only “to the standards they set for themselves,” but whether they will also live to up the standards they set “for others.” What exactly does Friedman think the Jews expected from Christian Europe? They certainly didn’t expect justice or safety; and, alas, they were right.

The standing norm in the Middle East, Friedman tells us, is what he calls “Hama rules,” the pitiless pursuit of political ends through bloodshed. Hama was a Syrian town of some 180,000 inhabitants, mostly Sunnis under the sway of the rebellions Muslim Brethren. It’s not altogether clear what happened to Hama in February 1982. We do know that Hafez Assad, a member of the small Alawite minority, determined to created a wasteland. A conservative estimate of the number of dead is 20,000. (Assad’s brother Rifat, who was in charge of the operation, boards that the figure was nearly double that.) In part owing to Friedman’s writings, Hama has become a metaphor for the brutal modalities of the Arab world. Hama rulers have governed in Lebanon for 15 years, as they govern Iraq today, as they governed Jordan in 1970. (Egypt used poison gas against other Arabs in the early 1970s.)

Does Israel play by Hama rules? Friedman, who faults others for what he politely calls a “lack of proportion” about Israel, seems a bit uncertain. He says that he is “convinced that there is only one man in Israel Haez Assad ever feared, and that is Ariel Sharon, because Assad knew that Sharon, too, was ready to play by Hama rules.” Is only Sharon, then, the dark mirror image of Assad? No, the equivalences run deep. Elsewhere he writes that Israel “had talked about ‘purity of arms’ to itself, but in the real world had learned to play by Hama rules, just like everyone else in the neighborhood.” Just like everyone else? This is the kind of moral parallelism that persuades writers of their daring. On “Nightline” a few weeks ago, discussion the abduction of Sheik Obeid and the hanging of Colonel Higgins, Friedman characteristically remarked that “it’s the Middle Eastern way. The Israelis know that, the Hezbollah knew that. The problem is, the Hezbollah are much better at the game than the Israelis, because they do it without any guilty conscience…Both sides have really used Higgins in this case, and exploited him in a very tragic way.” Never mind that the Israelis did not exploit poor Higgins, that his fate backfired on them and brought them under fire.

Suggesting that Israel’s conduct is equivalent to Syria’s and Iraq’s is like saying that American conduct during World War II was equivalent to the conduct of Nazis. What Friedman has done is to mistake similarities (and not many similarities) for essences. In some passages he shows that he himself knows better, as in his shrewd and textured analysis of the gangster regimes of Hafez Assad and Saddam Hussein and their routinization of Hama rules. But we are left with his crude refrain of equivalence. (Close readers will note that, though he decisively and explicitly includes Israel under the Hama rules, he absolves a handful of Muslim countries because their practice is based on “the more gentle Ottoman authoritarian tradition,” not the “more brutal, un-Islamic” kind. Qaddafi’s Libya? Khomeini’s Iran?)

Friedman is so overwrought about the defects of Israeli society that he can’t seem to distinguish between the reality of Hama rules and the reality of his disappointments. Everything is put through the wringer of his childhood dreams: not only the liberties Israeli security forces take with prisoners and procedures, or the sangfroid with which young Israelis loose bullets on young Palestinians hurling rocks and Molotov cocktails, but also Israel’s obsession with the Holocaust (as if Friedman is himself immune to the mawkish), the ambivalence about settlements, the hold on the political system of the minority of the ultra-Orthodox, the hypocrisies of official spokesmen. Some of his worries have a basis in fact. But what, exactly, is he worrying about? The Israel along the sea or the Israel in his fantasy?

Surely the fundamental contrast between Israel and the Arab states lies in the accountability of government to the governed. The long impasse in Israeli politics notwithstanding, such accountability is axiomatic in the Jewish state. Leadership stands or falls in response to the sometimes messy, but finally ordered, tally of the public will. Proof of such accountability runs like a thread through all of Israel’s history: in the Kahan Commission, for example, established by Menachem Begin after vast public and parliamentary protests to investigate Israeli involvement in the Sabra and Shatila massacre. Friedman is oddly cavalier about it: “An investigation which results in such ‘punishments’ is not an investigation that can be taken seriously.” He fails to see that a whole society was insisting that its government make a reckoning of its role in a moral calamity. (Only a few weeks ago the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that the Israeli army cannot destroy the homes of Palestinians accused of wrongdoing until they have appealed through the military courts. This, in the middle of a hostile uprising!)

There is a struggle, to be sure, being waged in Israel over the values and purposes by which the society will ultimately be defined. But Friedman seems cynical about that struggle, too. He believes, for example, that on the major question of the day, on the question of the occupied territories, the parties are united, that “differences between Labor and Lakud over the West Bank were quite insignificant. The only difference between them was in rhetoric.”

But no such differences and no such accountability can be attributed to any Arab system of government. Arab political life does not include public apologies and public explanations. Around the world we are now in an era of great democratic expectations. Only a few months ago people of goodwill everywhere were stunned by the bloodletting in Tiananmen Square, but such an event wouldn’t raise an eyebrow in the Arab orbit, and probably didn’t. (According to People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist newspaper, Arafat wrote Jiang Zemin, the new secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, “to express our extreme gratification that the friendly People’s China has restored normal order after the recent incidents.”)

Friedman is dead to a good deal of Israeli life. For example, to the Israeli army. Given the fact that Israel has not, in its entire existence, had a single day of peace (even when there were no occupied territories), it shouldn’t shock that the army permeates the entire society. This is, almost in the old-fashioned sense, a nation at arms. But it is a little shocking that Friedman deals with the army mostly with anecdotes about a few of its boorish and brutish soldiers, with stick figures used as symbols to suit his purposes. Surely what is remarkable about this central institution in Israeli life is that it has never posed a peril to democratic norms or practices. At the same time, civilian authority has generally respected the professional independence of the military. Under the present government, for example, the army has been able to maintain its policy of restrained response to the intifada, despite continuous outcries from many of the Likud’s hard-core constituents. Yes, there have been crimes and abuses (some of them corrected by the army, some of them corrected by the courts, some of them uncorrected). But the top brass are doves, who see only a political, not a military, solution to the problem of a nationalist uprising. Some famous military controversialists notwithstanding, this army never allows itself the quick fix of mass killings. There are army norms that constrain the range of what is militarily permissible. Is there an army that does better?

From Friedman’s book you learn much about Lebanon but little about Israel. How does he want Israel to live in its brutal neighborhood? He rehearses the grim prognostications of others without taking them seriously, recoils from realpolitik, lectures about Hama rules, and is silent. Instead he invests the United States with chimerical powers to bring peace. He seems to believe that the Arab-Israeli conflict is hospitable to American-style deal-making. Thus, in a foolish passage, Friedman laments the loss to history that Robert Strauss, President Carter’s envoy to the region, “did not stay in his job long enough to see it through.” (Friedman has a weakness for homespun wisdom, and was impressed by Strauss’s comment on the West Bank: “I don’t know why any one of them would want it and why the other would give a damn.”) No doubt he has been confirmed in his faith by James Baker, the pol par excellence, who is Friedman’s current beat.

Thomas Friedman doesn’t even hint at alternatives to policies he criticizes. This makes his criticisms seem both abstract and a little irresponsible. Up to the day before yesterday, almost all of Israel’s neighbors denied its right to exist. Now there is a cold peace with Egypt, and parts of the PLO have been coaxed and cajoled into at least a ritualized formula of acceptance. But other countries and other Palestinian elements maintain their hard line. Weapons flow to the region like rivers to the sea, weapons of mass destruction, chemical and biological weapons. It is true that Israel is a major military power, but with reason: even in the best of circumstances, Israel will live not only in physical danger but in moral ambiguity. Statecraft, after all, is not the road to sainthood. But, security and survival are also moral ends; and if realpolitik is required for them, then it, too, is a moral thing.