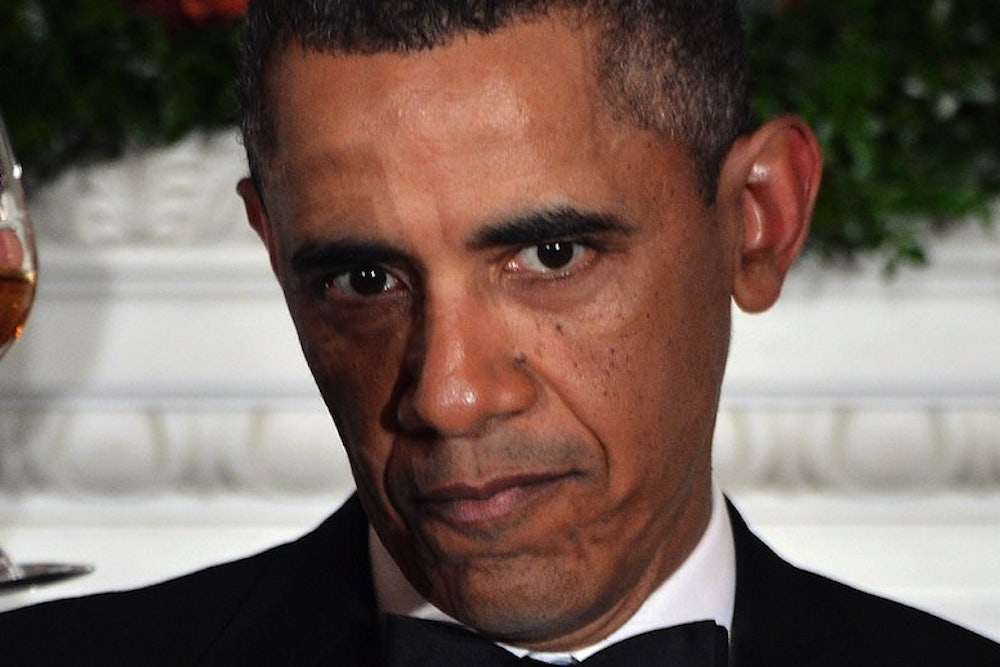

Last night, Barack Obama bowed to establishment convention and had what must have been a torturous dinner with twelve Republican senators. Before The Washington Post editorial board gets weepy-eyed over this banquet of bipartisan schmoozing, let’s make one thing clear: Even if he were the most prolific, solicitous, all-around charmingest dinner-host the capital had ever seen (think Kay Graham meets Dick Cavett), Obama would not have accomplished much more than he did the last two years, and possibly less. The reason, as many other commentators have spelled out, is that the limits to grand-bargaining aren’t social but structural. They’re the result of the two parties sorting themselves out along ideological lines; of a sharp move rightward among Republicans; and of basic partisan math in the House and Senate. It’s completely delusional to think these factors could be altered by a few more dreary gabfests at the Jefferson Hotel.

Having said all that, I kinda think it could work this time. Sure, the country is as polarized as ever. Sure, the Republicans are nuttier than ever. And, sure, they have the numbers to thwart Obama’s agenda in Congress. But here’s the thing: Even with all that, the deal Obama has put on the table is very, very close to the deal John Boehner himself publicly offered last fall,1 and which several Republican senators have supported in the past. Which is to say, there’s no obvious structural reason why a deal couldn’t happen.

In fact, pretty much the only major difference between what Boehner has offered and what Obama is offering now is the number of steps it would take to get the deal done. Obama is proposing that it happen in two steps: The first step was to raise $600 billion through tax-rate hikes during the fiscal cliff deal in January. The second step would be to raise several hundred billion dollars more by closing tax loopholes in exchange for about two times that amount in cuts to entitlement programs and other spending. Boehner, for his part, has proposed similar amounts. He just wanted all the tax-rate hikes, loophole closings, and spending cuts to happen in one big push at the end of last year.

Admittedly, the politics of Obama’s two-step are a bit trickier than if we’d we worked it all out at once: Right-wingers haven’t stopped fuming over the tax increases Obama foisted on them; it would have been better to hit them up for everything pre-fume. But substantively, there’s almost no difference between a deal done in one step or two. It mostly comes down to arbitrary emotional posturing—or, as the psychologists call it, “whining.” And what better way to defuse emotional objections than with a symbolic gesture of goodwill? Like, say, dinner.

Of course, more important than the dinner-table chatter is the underlying dynamic Obama is trying to create. We already know Boehner isn’t opposed in principle to the kind of deal we’re talking about. His Senate counterpart, Mitch McConnell, almost certainly isn’t either. (McConnell has been a much more reliable negotiating partner for the White House these past two years.) The problem is that, post fiscal-cliff tax increase, neither man can afford to be seen as embracing such a deal, lest they court a nasty conservative backlash that could cost them their jobs. So the trick is to find a way to make the deal happen while maintaining the pretense that it’s a fate worse than death.

Here’s where Obama’s charm offensive comes in. By reaching out to Republican senators who are sympathetic to the deal, Obama just may succeed at splitting some of them off from their leadership, giving him the 60 votes he needs to pass it in the Senate. McConnell can then curse his colleagues’ treachery in public while privately cheering the outcome. In fact, my guess is that once Obama has the magic 60 votes, he will get several more, since many senators will want to claim a share of the credit.

At this point, the House will be in a tough spot. The Senate has just passed a deficit-cutting grand bargain that will prune hundreds of billions of dollars from programs like Medicare and Social Security (something conservatives insist they want) in return for a small amount of tax revenue obtained through the closing of loopholes (which conservatives claim to hate). We know the bill is likely to have a fair amount of public support, since the public already backs this deficit-cutting approach in the abstract, and since you can add 10 to 20 points of public approval to just about anything that passes with bipartisan support.2

This, in turn, will be Boehner’s cue to appear before his caucus and inform them that the deal is a “crap sandwich”—offensive in too many ways to count (even though it was largely his idea)—but what can they do? The whole country is getting on board with it. (This, as I noted in my recent mash note to the speaker, is his signature move.) Worse, he might add, the win they thought they’d notched when they stared down Obama over sequestration isn’t looking so winning any more, as defense contractors get ornery over the Pentagon cuts Boehner once claimed to be Zen about. There will be much gnashing of teeth among the GOP rank and file. But, in the end, they will accept that Boehner must bring the Senate-approved bill to the floor, where it will pass with a big assist from Democrats.

How likely is this scenario? Well, I wouldn’t exactly call it probable. It’s going to be hard to get those first few Republican takers in the Senate given all the noise on the right. But if Obama does pick them off, I suspect the rest could fall into place pretty quickly. In the end, a few overcooked steaks at an overpriced restaurant aren’t going to render the historical forces acting on Washington any more forgiving than they were during Obama’s first term. But they just may nudge Republicans into doing what most of them want to do anyway.

When we left off the grand-bargaining last December, Boehner was offering about $1 trillion in revenue through a mix of tax-rate increases and loophole closings, paired with about $1.2 trillion in spending cuts; Obama was offering $1.2 trillion in revenue and, depending on how you do the math, about $1 trillion in spending cuts. By Washington standards, this is an eminently bridgeable divide.

Of course, it’s true that Obama has believed himself to be very close to a deal with Boehner before, only to see the speaker walk away from the table once it was clear his House members would go completely nuts if he actually signed off on it. What’s different this time is that Boehner made his offer publicly as opposed to entirely behind closed doors, suggesting his members had softened on it a bit. And that, more recently, Obama has shown an inclination to bridge most if not all of the gap by moving in Boehner’s direction.

Yes, the cuts to Medicare and Social Security could be controversial politically. And they’re substantively questionable—I personally don’t like them. But I suspect the reaction on the left and from the public will be muted given the support of Obama and Senate Democrats.

Correction: This article originally stated that Barack Obama's offer would raise several hundred billion dollars in revenue in exchange for two-to-three times that amount in spending cuts. In fact, the spending cuts would amount to just under two times the revenue increase.