There is a new Iron Man movie opening this month, which means we are being subjected to the force of nature that is the Robert Downey Jr. publicity tour. By now, his persona is familiar: debonair, insouciant, and lovably arrogant, in a faintly bemused kind of way. Of course, this description could also be applied to Tony Stark, the outrageous tycoon Downey plays in Iron Man—not to mention the character in his second blockbuster franchise, Sherlock Holmes, who is basically Tony Stark with an English accent.

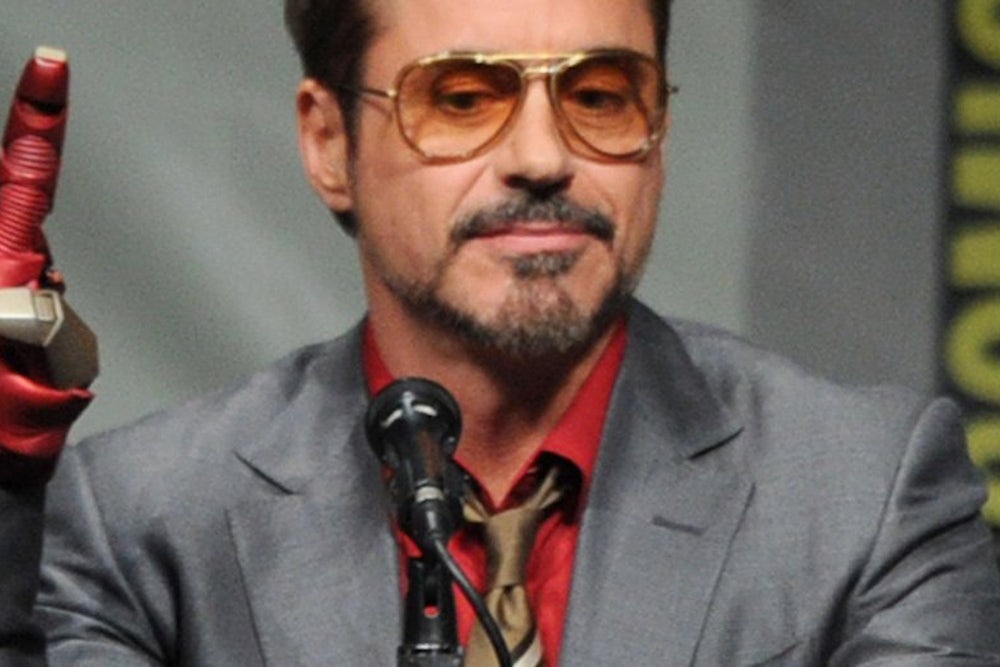

In public, Downey inhabits this same persona with complete and unembarrassed commitment. There is no other actor who works so hard to sell a movie: When he stopped by Comic-Con last summer to promote Iron Man 3, he shimmied down the aisle to Luther Vandross as if an Oscar depended on it, high-fiving fans with an ersatz laser embedded in his right palm. “How much do I love you?” he asked the screaming crowd, utterly deadpan. “Question number two,” he continued, in a mock-sexy whisper, “How much do you love me?”

For nearly a decade, from the mid-’90s until the early 2000s, Downey was the biggest disaster in Hollywood—excruciating to watch because he had so much potential on screen and was such a mess in life. A former child star, Downey had been hailed as the most gifted actor of his generation, known for a string of brilliant performances in which he disappeared completely into his characters—including, memorably, the title role in 1992’s Chaplin.

But his prodigious talent was matched only by his prodigious drug habit, which began when his dad, a director of underground films, introduced him to pot before the age of nine. By the late ’90s, Downey was less famous for his acting than for his glassy-eyed mug shots, splashed over the tabloids after some misdemeanor involving drugs or guns or both. No studio would insure him. He always seemed to be in and out of rehab, in and out of jail. As he told a judge, “It’s like I’ve got a shotgun in my mouth, with my finger on the trigger, and I like the taste of the gun metal.”

Now Downey is the biggest film star on Earth. Last year, he earned $50 million just for his appearance in The Avengers—and he isn’t shy about admitting that the size of the paycheck is a major motivation. When he was asked recently whether he would ever star in a smaller film, he responded, “Even the stuff that I would want to do as an artistic expression ... I would like to do for a price, and I would like to be pretty much sure that it was going to be a hit before I started.” This may sound like the cynical admission of a sellout, but the real story is somehow more charming. After falling prey to the worst excesses of Hollywood, it was Hollywood in its purest form—the massive, corny, buckraking, blockbuster machine—that saved him.

When Downey finished a yearlong stint in prison, in the early 2000s, it looked like he was going to follow the time-honored path of regaining respect through small, arty projects. He recorded an album of pop ballads, but chafed at how little money he made. He agreed to write a memoir, and then abandoned it. He told GQ that, after Kiss Kiss Bang Bang was released to good reviews and poor ticket sales in 2005, he thought, “Where’s mine?”

As a friend of his explained, prison had cleansed him of “artistic neuroticism.” He had experienced the depths of failure, and now he wanted tangible, measurable success. Soon, Downey would come to see the commercial success of his movies as a validation of his recovery.

And so, when Marvel Studios was searching for its Iron Man, Downey desperately sought the role. “Under no circumstances are we prepared to hire him for any price,” the studio informed the film’s director. But Downey persisted and rehearsed around the clock for weeks. When he got the part, he constructed not just a character but a brand based on his own bad-boy image, in precisely the way the Hollywood playbook recommends. Thus, Tony Stark drinks scotch in a Humvee in Afghanistan. (“This is the funvee. The humdrum-vee is back there,” he tells a soldier.) When he was cast as Sherlock Holmes, he turned the tweedy detective into a fast-talking tough guy who deploys martial arts against the evildoers of London. In other words, a Holmes like himself. (He took up the fighting technique Wing Chun after prison.) Both characters are wonderfully likable, even when the films are not.

More than one person who knows him told me that Downey deliberately channels his manic intensity into the financial side of movie making. “I made it my business to educate myself,” he explained to one interviewer. He is involved in every aspect of his films, from tinkering with screenplays to marketing strategy to developing new consumer bases for his franchises. A year ago, he gave an interview to an obscure magazine called Success, apparently for no reason other than the sheer enjoyment he derives from discussing the intricacies of multi-platform initiatives. “The thing is,” he observed, when explaining his acting choices, “you’re either involved in a certain product design that’s a one-off, or you’re involved in a product line.”

And, since China may hold the key to Hollywood’s financial future, he promotes his films there energetically. “I’m interested in all things Chinese, and I live a very Chinese life in America,” he announced at a press conference in Beijing in April. “I am very interested in martial arts, and I am very interested in traditional medicine.” Entertainment writers accuse him of crass shilling, but in his desire to see his movies succeed, Downey is totally sincere. “This big globe-hopping thing,” he explained on yet another Iron Man press blitz, “my ego is saying this is a victory tour.”

It’s not the future audiences might have envisioned when Downey first appeared on-screen, exuding a joyful charisma and more talent than he knew how to control. Back then, he might have been expected to evolve into a Daniel Day-Lewis–style craftsman, subsuming himself in a series of legendary performances. Downey, however, found redemption in the opposite direction. “People will come up to me and go, ‘Dude, how do you do it? How do you dress up and play these ... ?’ While whatsisname is shooting the next David O. Russell or whatever,” he said in the GQ interview. “There is no guarantee that doing a movie you think is ‘important’ isn’t going to be the worst piece of tripe. ... Or that this kind of two-dimensional genre movie I’m doing isn’t actually going to be thoroughly entertaining. Isn’t that why you went to the movies to begin with?” The best use of Downey’s boundless energies, it turns out, lies in becoming the most successful version of himself.

Follow Isaac Chotiner on Twitter @IChotiner.