The Beautiful Atom Bomb was, in her time, a rare talent. She had a waist on a gyroscope that attached to an ample bottom, which she could shake with such alarming ferocity that the laws of physiology seemed reversed: She didn’t control it, it controlled her. Her vibrating posterior propelled her right across the movie screen like an outboard motor, and she would saddle up to a stunned onlooker, hindquarters aflutter, and induce an immediate relaxation of the jaw muscle. Mouths fell open, cigarettes leaped from lips, eyes bulged.

The tradition-bound Pasthun belt of Pakistan is not a place you’d expect to produce a sex symbol who lorded over young men’s imaginations for nearly two decades, but the Beautiful Atom Bomb is singularly responsible, it is safe to assert, for the overwhelming majority of impure thoughts suffered in the darkened bunks of Pakistan’s madrassas. In the conservative Pashtun tribal belt, Musarrat Shaheen, the star of Haseena Atimbum (Beautiful Atom Bomb) and a lengthy catalogue of similarly titillating titles, occupied a societal role roughly equivalent to that of Pamela Anderson.

And now she is running for a National Assembly seat in Parliament.

Naturally, her campaign has caused a stir. To some, it’s a mockery. To others, a sign of progress and open-mindedness, even if her prospects are generally considered to be dismal—of the eight serious contenders for the seat, which is determined by simple plurality, only two are believed to have a shot.

She has run once before, in 1997, but didn’t then have the legions of amateur pundits armed with cellphones and Facebook accounts to turn her long-shot race into an Internet meme. This time, like celebrity-turned-politicians the world over, what she lacks in electoral prospects she has more than made up for in the social-media circus that has accompanied her campaign. She is walking (or more accurately, shimmying) evidence of the fact that even in a conservative Islamic country, politics and theater are never too far removed.

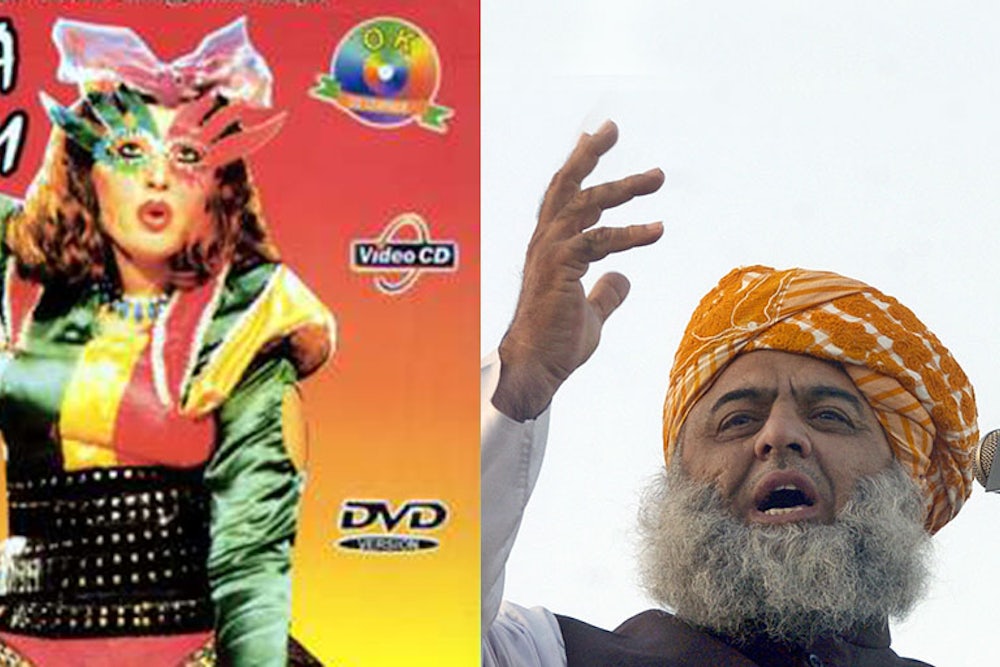

The theatrics are amplified by the fact that one of her opponents, who is favored to win the seat, is a conservative, tradition-bound mullah. Nicknamed “The Diesel Mullah” because of his wartime profits on petrol shipments into Afghanistan, Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman is chief of Pakistan’s most conservative religious party, Jamiat-i-Ulama-i-Islam-Fazlur (JUI-F), and a powerful cleric with close ties to the Taliban. Somehow, though, Shaheen has managed to get under his skin.

The stakes are high. This Saturday, Pakistani voters will brave the threat of Taliban attacks to decide who will preside over a critical juncture in the country’s history. The next government of Pakistan will have its hands full, dealing with the ripple effects of the NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan, ascendant terrorist organizations poised to exploit the power vacuum there, the woeful underdevelopment that continues to plague Pakistan despite the huge aid payouts it receives (including nearly $20 billion since 9/11 from the U.S. alone, according to DOD), and a violent separatist movement growing in Baluchistan, the country’s biggest province.

The elections also represent a milestone for Pakistan. The country just completed a civilian government for the first time in its entire history—every previous attempt saw Parliament dissolved under military coup, or dismissed by the president for one reason or another—so there’s excitement even among the most jaded observers of Pakistani politics (of which there are admittedly many). Add to the mix a bevy of colorful candidates like playboy cricketer–cum–political hopeful Imran Khan, throw in that more than 90 percent of Pakistanis are dissatisfied with the way things are going in the country, and you’ve got all the ingredients for the biggest, most important, most anticipated elections in the country’s young history.

The stakes are high for the West as well, as Pew polling shows that not only do Pakistanis generally not care for America, they generally don’t care about not caring: Fewer than half believe that improving relations is important. And as the country that is home to the terrorist groups most capable of reversing America's tenuous progress in the region, the wavering on the Pakistani street between contempt and agnosticism makes it hard for U.S. interests to operate there—whether we’re talking about Seal Team Six raids, drone strikes, or trade relations.

In what has become a campaign season full of high drama and regional implications, it is the race in NA-24—the city of Dera Ismail Khan, strategic for its proximity to the tribal agencies mostly controlled by Taliban—that has become one of the hundreds of national assembly races thrust into the national spotlight. That’s where Shaheen, the Beautiful Atom Bomb, is taking on Rehman, the Diesel Mullah. Shaheen may be a long shot, but her entry into the race was a gift to the nation's satirists—and a headache for Rehman—as cartoons and Photoshopped images of the two dancing and carousing have become Internet memes. That's because Shaheen and Rehman are about as different from one another as two humans are capable of being. She's the pretty, middle-aged former Pollywood star with the wry smile, and he's the frumpy, orange-turbaned 59-year-old with a sallow face and a linty half-moon beard. She's a caricature of all the things the Taliban finds blasphemous, and he's an advocate of Sharia law whose network of madrassas produced thousands of Taliban in the early nineties. She's a political neophyte building a party from scratch, and he's the mullah son of Mufti Mahmud, who was a powerful cleric and right-wing politician himself.

But Rehman is more a shrewd politician than instransigent cleric. Even in a country where electoral politics are a constantly twirling orrery of political affiliations, his talent for self-reinvention is singular. His party loudly opposed women being head of state in the late 80’s when Benazir Bhutto was becoming popular, saying she had no chance, and that it was against Sharia Law. Then she won, becoming prime minister, and he joined her government. He is something of a godfather to the Taliban, standing atop a party that managed madrassas in refugee camps throughout the country’s Northwest, the very seminaries from which the Taliban first emerged, and then in 2008, suddenly reversed tack and distanced himself from the Taliban so that he could present himself as a moderate. (Now he’s back to claiming special status with them in order to cast himself as the best hope of achieving peace, a claim Shaheen is quick to skewer.)

Rehman has a talent for finding the right party at the right time, shedding ideologies and picking up new ones like some do clothes. There are so many constantly shifting, countervailing forces that politicians have to continually contort themselves to remain relevant, and those who endure it have learned to treat ideology as a secondary concern, a kind of political tool to be picked up and put down and not become too attached to. At this, he has proven expert.

But the Shaheen has chosen not to target Rehman’s political hypocrisy, which is not uncommon among Pakistan’s career politicians. Rather, she has appealed to a populist impulse, echoing the 2012 U.S. presidential campaign by trying to gin up resentment for his inherited wealth. When she submitted her nomination papers in March, she said she sought to protect the local people from exploitation by the mullah and his ilk. “There is a mobile phone instead of a tasbih [prayer beard] in the mullah’s hand,” she said. “Instead of sitting in the mosque, he is roaming around in Pajeros and Land Cruisers.” She called out the thousands of acres of land Rehman owns, and how he “lives a lavish life with full luxuries.” And, she reminded journalists, whatever she owns is a result of her “own hard work.”

Here, the Diesel Mullah is a softer target. So to defend against a populist uprising against him, he did something surprising—he outflanked her on the left.

At the end of March, he held a big rally in Lahore, a kind of political away game on the big-city home turf of the more cosmopolitan politicians with whom Shaheen claims kinship, like the industrialist and former prime minister Nawaz Sharif and the former cricketer Imran Khan. Rehman got up on stage and shocked everyone by talking not like a cleric, but like a socialist. It was as if he asked an advisor how to expand his base, and was handed Marx. He condemned “colonial masters,” and an unjust class system. “No feudal lord would be able to banish the tenant from his land by force,” Rehman said, and if his party was elected, "The worker should be given his right in order to make the country a welfare state." He even allowed dancing and singing at the rally, a departure for a man who had always condemned such pastimes as petty and blasphemous.

When asked about Shaheen, Rehman has learned to respond in the patrician manner that male politicians the world over often use when speaking of pesky female challengers: He talks down to her. He’s resisted the urge to do what everyone wants him to do—question her morals, call her unclean, call her a harlot. Instead, he just paints her as irrelevant. “We have no problem with Mussarat," Rehman's spokesman wrote to me in an email. “She has every right to contest. Of course people will decide, and we see her no threat whatsoever…”

The Diesel Mullah may be genuinely unconcerned about the Beautiful Atom Bomb, or at least, he may be far more concerned with one of a handful of other candidates running for the same seat, but if there’s one constant in Pakistani politics, it’s that you can never be too sure where the real threat lies. And Rehman had a cruel reminder of that this Tuesday, when a motorcycle bomb exploded at a rally for his Islamist party, JUI-F. It is not the first time the Taliban have attacked JUI-F, but it is a crucial strike against his legitimacy, because he made it a part of his campaign platform that he is a sort of Taliban whisperer, and would bring peace by negotiating with them. The optics are unfavorable: A man who appeared to be above the fray, Rehman may not have his house in order after all.

So he’s done what any good politician would do: deflect. He’s thrown journalists red meat and kept them off the Taliban story, joking about himself as prime minister, reciting a now-tired refrain about how one of his political rivals is a Jewish agent, and even taking to Twitter—in English—to show a more reasoned side. And when Shaheen tried to keep him in a conservative box by telling reporters she was worried he might issue a Fatwa against her, he once again proved too nimble for the accusation to stick. He made one last move no one expected: He appealed to women.

“In Islamic history be that agriculture, business or war, women have been on the forefront,” he said in a statement. “Women should be encouraged to cast votes particularly in tribal areas as they can contribute to the welfare of this country.”

While it’s hard to say whether the challenge from a provocative starlet with popular (if not necessarily political) appeal pushed the Diesel Mullah to court the youth vote and appeal to women, it was impossible to ignore the profusion of online satirizing at his expense that has been going on since the Beautiful Atom Bomb shimmied her way into the race. Searches for him turned up pictures of her, and for every normal photograph of Rehman online, there was a doctored one with someone's tongue-in-cheek homage to his titillating challenger. He suffered less from an Atom Bomb than a Google Bomb, and now the old cleric with the Taliban ties is celebrating women’s enfranchisement and talking to young people on Twitter. Perhaps that's progress.