White people simply love to spend their free time walking up and down mountains and sleeping in the forest. Search “hiking” in Google Images and see how far you have to scroll to find a nonwhite person. Ditto rock climbing, kayaking, canoeing, and so on. That white people love the outdoors is so widely accepted as fact that it’s become a running joke. The website Stuff White People Like has no less than three entries on the subject: “Making you feel bad about not going outside” (#9), “Outdoor Performance Clothes” (#87), and “Camping” (#128). The latter entry reads, “If you find yourself trapped in the middle of the woods without electricity, running water, or a car you would likely describe that situation as a ‘nightmare’ or ‘a worse case scenario like after plane crash or something.’ White people refer to it as ‘camping.’”

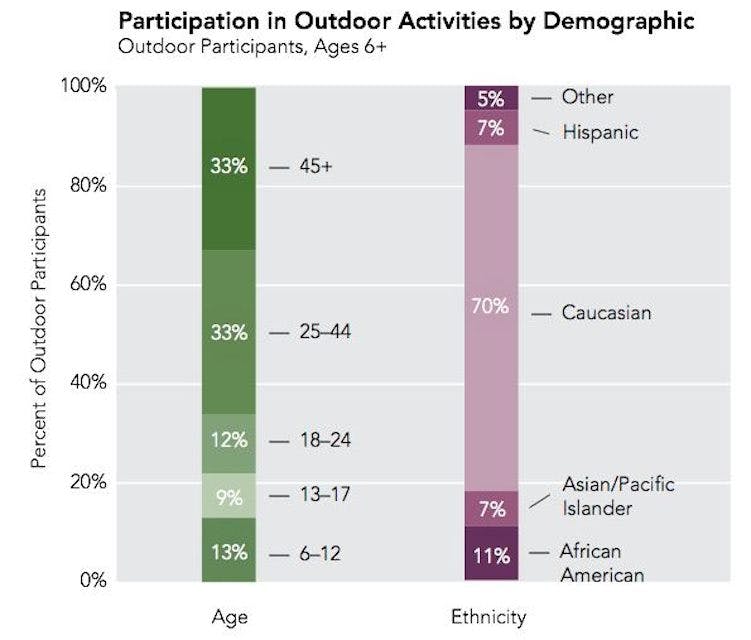

That quote is almost certainly how most blacks, Latinos, and other minorities view hiking and camping. The Outdoor Industry Association—the top outdoor-recreation lobby in America (and based in Boulder, naturally)—insists that outdoor enthusiasts “are all genders, ages, shapes, sizes, ethnicities and income levels,” but research by their own nonprofit organization, The Outdoor Foundation, shows underwhelming diversity. Its 2013 outdoor participation report notes that last year, 70 percent of participants were white. “As minority groups make up a larger share of the population and are predicted to become the majority by 2040, engaging diverse populations in outdoor recreation has never been more critical,” the report reads. “Unfortunately, minorities still lag behind in outdoor participation.”

In a front-page story today, The New York Times details these very problems facing the National Park Service—only one in five visitors to NPS sites are nonwhite, according to a 2011 study cited in the article—and the “multipronged effort to turn the Park Service’s demographic battleship around.” Clumsy metaphors aside, the article does a respectable job at detailing the various efforts—namely outreach, all-expenses-paid trips, and creating more national monuments recognizing minority figures in U.S. history—to increase minority participation. Less complete are the reasons the Times gives for that low participation.

Many white Americans who grew up going to the parks had towering figures of outdoor history — not to mention family tradition — blazing the trail as examples. And those examples, like Daniel Boone and the fur trappers of the Old West, tended to be white.

I’m white, and have been hiking since I was a prepubescent. I assure you that I wasn’t inspired by outdoorsmen of yore, if I even knew their names. I grew up in the Northeast, raised by parents who have never pitched a tent. My love for the outdoors formed over summers spent at a sleepover camp in upstate New York, where we’d go on days-long trips in the Adirondacks. That is, I fell in love with the outdoors because I had the means to do so. I don’t know what Camp Dudley charged in the ‘80s, but today a month there costs $4,800.

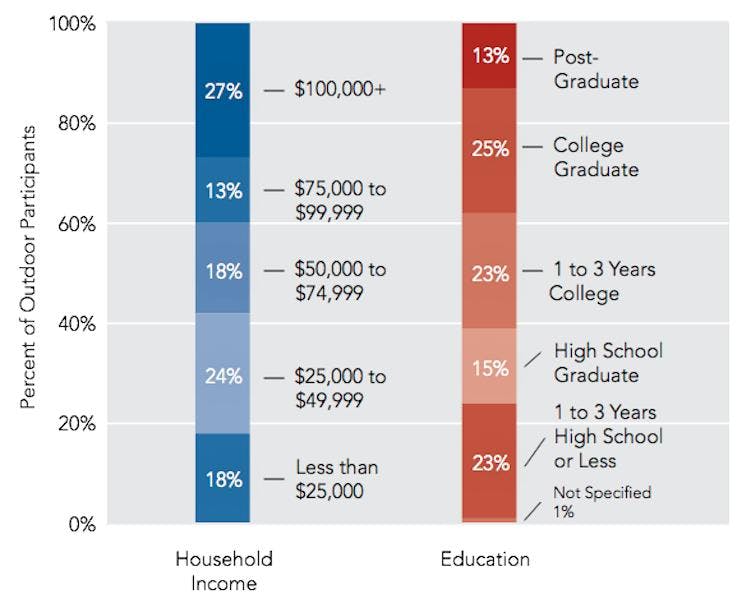

As Stuff White People Like says, “In theory camping should be a very inexpensive activity since you are literally sleeping on the ground. But as with everything in white culture, the more simple it appears the more expensive it actually is.” You may need to fly to your destination; otherwise, you’ll need a car and a full tank of gas. A backpack, tent, and the necessary gear will run you at least $1,000. And then you need some free time—which, if you work two jobs, you probably don’t have. That may explain why 40 percent of outdoor participants come from households with incomes of $75,000 or more, according to the Outdoor Foundation’s report.

The Times managed to find a nonwhite person who enjoys hiking. Carol Cain, a 42-year-old New Jersey resident of Dominican and Puerto Rican roots, was apparently day-hiking in Washington’s Olympic National Park when she told the paper, “We’ve been here for two days, walking around, and I can’t think of any brown person that I’ve seen.” The article later reports: “The idea of roughing it in a tent, however, can feel to some people like going backward, said Ms. Cain, a first-generation American who said the stories in her family about escaping the hard rural life still resonate.”

This strikes me as the truest line in the piece—and the biggest hurdle to diversifying outdoor participation. Yes, there are economic barriers, but the cultural ramifications of those economic barriers are more devastating, as they ripple across generations. Say you’re a black teenager in Washington, D.C., or a Hispanic teenager in Denver. Statistically, there’s a good chance you have never been to Shenandoah National Park or Rocky Mountain National Park, respectively, because your parents had neither the means nor the interest. Then you grow up, get a good job, and enter a higher income bracket. Why on Earth would you use your hard-earned vacation time to spend a week eating freeze-dried food in the woods—rather than, say, reclining at a seaside hotel on Miami Beach, frozen margarita in hand?

Even I can’t answer that question—not without embodying the parody of a white man, anyway.

Update (7/13/2015): Since this article was published nearly two years ago, many readers have pointed out that the demographics of outdoor participation, as described in the Outdoor Foundation’s report, are not dissimilar from the demographics of America, which is 77.7 percent white. However, that report defined outdoor participation as one of 42 outdoor activities, including adventure racing, car camping, hunting, and skateboarding.

What about hiking and camping, specifically?

The Outdoor Foundation found that 86 percent of campers are white. As for hiking, I was unable to find a truly comprehensive nationwide study. National Park Service visitor surveys, like this one from 2008-2009, are not very useful because the NPS includes not only national parks but also historic sites, battlefields, parkways, and other non-hiking terrain. (Moreover, hiking is hardly mandatory in many national parks: You can visit Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park—where 92 percent of visitors in 2011 were white—without getting out of your car.) The most relevant study I found was conducted by the U.S. Forest Service, which manages national forests and wilderness areas—backpacker territory, in other words. It found that between fiscal years 2008 and 2012, 95 percent of visitors were white. That corresponds with my extensive, if anecdotal, experience as a lifelong hiker.