The only two certainties in life are death and taxes (at least since the Supreme Court’s 1916 decision upholding the income tax). That has meant that throughout the history of the Supreme Court, with its constitutionally mandated lifetime appointments, presidents and justices have attempted to game both turbulent political winds and the vagaries of mortality by strategically filling seats held by old-timers with younger justices of similar ideological bents. “It’s legitimate if all of them do it,” says Tracey George, a professor of both law and political science at Vanderbilt. “It’s not disconcerting in a world where we know all the justices behave this way. In general, they step down when the current president matches their preferences and/or that of the president who has appointed them.” In other words: Justice may be blind, but the justices are not.

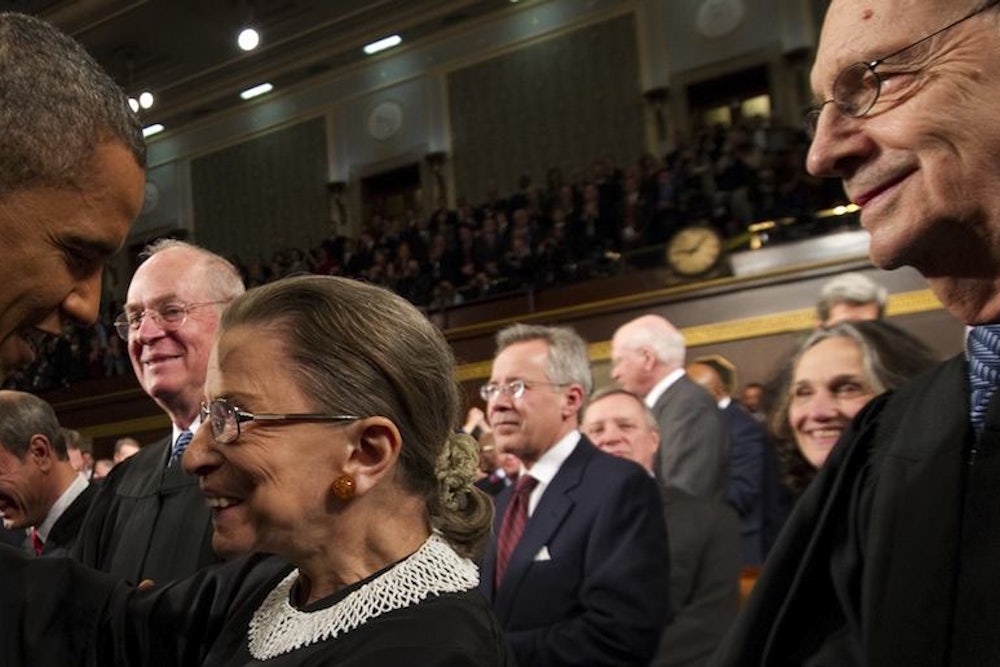

Currently, with a Democratic presidency and Senate majority (refresher: when it comes to federal judges, the president appoints, the Senate confirms by a simple majority), eyes are turning to two aging, Bill Clinton-appointed liberal justices: Stephen Breyer, 75, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 80. The thinking is that since the amount of time they can continue to serve is unknowable and, likely, not particularly substantial, they may want to get out while the getting-out is good. In 2011 in The New Republic, Randall Kennedy respectfully called on them both to retire for this reason.

Because Ginsburg is frail by appearance and has survived two bouts with cancer, including pancreatic cancer not five years ago, several commentators have singled her out as ripe for retirement. (Although there is a countervailing meme, given articulate force in the “Notorious R.B.G.” tumblr, that Ginsburg is tougher than everyone else.) “Ruth Bader Ginsburg Must Go,” is the headline of an article Salon published earlier this year. And a 3300-word profile of Ginsburg in the latest issue of Washington Post Magazine was framed entirely around this question. When asked, though, she said she does not plan to retire anytime soon. “I think it’s going to be another Democratic president,” she argued. “The Democrats do fine in presidential elections; their problem is they can’t get out the vote in the midterm elections.”

But, to be blunt—and with all due respect to Ginsburg, a brilliant jurist whose pre-court work on women’s rights alone would have made her one of the most influential lawyers of the past half-century—Ginsburg doesn’t know that the next president will be a Democrat. (Nor does anybody else!) However, several experts say, any effort by outsiders to try to persuade Ginsburg (or Breyer) to step down under this logic would be widely perceived as indecorous, and anyway would be of little practical use.

“If Justice Ginsburg makes the calculation that it’s better to leave now because a Republican might be elected president and she trusts Obama to make a better decision—it’s one thing for her to make that decision, it’s another for Obama to,” says Keith Whittington, a Princeton politics professor. “It seems too much like the president trying to manipulate the composition of the court.” He compares it to the way that today we frown on President Franklin Roosevelt’s attempt to “pack” the court by drastically increasing the number of justices—and the way nobody today is bothered by the fact that, after his court-packing gambit failed, Roosevelt proceeded to appoint more than a half-dozen justices via the normal route, laying the groundwork for the Warren Court.

“Certainly there has been in the past—and the evidence is admittedly not directly from the parties—reason to believe that there have been communications between the White House and certain justices on the Supreme Court about their plans,” George says. However, she adds, “more often [it’s] the justice signaling an intention to step down.”

The way we talk about this is extremely odd. The oddness results from two semi-conscious self-delusions: That lifetime appointments could mean letting the chips fall where they may, and that justices aren’t political in the same way members of the other branches of government are. “We remain a little weird about how explicitly ideological we should be in appointing or confirming judges, so we do this Kabuki dance about what it is we're doing,” says Whittington. “But having said that, I think it’s possible to make a distinction between, ‘When you have the option of filling a seat, how do you go about it?’ as opposed to, ‘You would like to have the option, how do you go about creating it?’” He adds, “There’s a bit of pretending, but there’s also a bit of them saying, ‘Whose decision is it?’”

Are there ways to regularize the selection process so that this bizarre issue doesn’t come up anymore? Several people I spoke to proposed making “senior status” more active for ex-justices. Other federal judges can take senior status, notes Albert Yoon, a law professor at the University of Toronto: “It’s actually a pretty great gig—you get to hear whatever fraction of cases you want, you get paid the full amount and any raises.” By contrast, he adds, “If you’re a Supreme Court justice, you can take senior status effectively, but it’s not the same job—you get to sit and hear appellate cases.” In other words, it is much more clearly a demotion.

The other obvious solution, of course, would be to end lifetime appointments. A CBS News/New York Times poll last year found that 60 percent of Americans oppose lifetime appointments for Supreme Court justices. The problem is that ending lifetime appointments would require a Constitutional amendment, which in turn would require two-thirds majorities in the House and Senate and passage by three-fourths of the states. No less than Justice Antonin Scalia, in his recent interview in New York, admitted that amending the Constitution is a too-steep proposition: “The one provision [of the Constitution] that I would amend is the amendment provision,” he disclosed. “With the divergence in size between California and Rhode Island—I figured it out once, I think if you picked the smallest number necessary for a majority in the least populous states, something like less than two percent of the population can prevent a constitutional amendment.”

Of course, if Ginsburg is right about the next president being a Democrat, then Scalia, 77, will surely treasure his own lifetime appointment.