The End of the Rainbow

November 1, 1993

If polls are to be believed, next Tuesday will see the election of Bill de Blasio as Mayor of New York. As The New Republic's Michael Schaffer recently noted, the full-throated liberal's takeover from Michael Bloomberg serves as a symbolic end to the age of the imperial mayor—the business-frieldly, centrist leaders who ran New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington, and a number of other reliably liberal cities during the past couple decades. De Blasio's campaign, like those of the progressives who will surely follow his example in other cities, channeled the dissatisfactions of voters who felt left out of the upscaled, gentrified new city—and who perhaps took for granted the improvements in government performace in the years since a full-throated liberal last ran the city. Twenty years ago, as that era was just dawning, Jim Sleeper published a New Republic cover story saying goodbye to the last generation of big-city mayors, who were similarly dispatched by opponents who had appealed to the anger of voters who felt left out, while relying on a population that took for granted some of the improvements their generation had heralded. Here's Sleeper's piece from November 1, 1993:

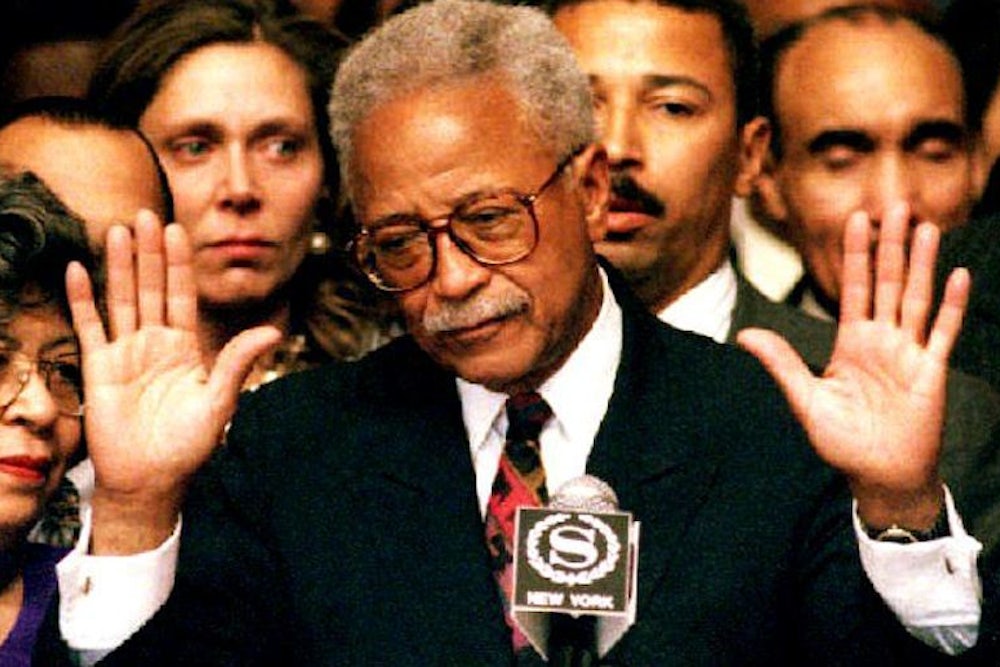

On a trip to Israel in July, New York Mayor David Dinkins's eyes welled with tears as he recalled a close friendship with his accountant of many years, the late Abe Nowick, a Jew, in which racial differences had mattered so little that "one didn't know what the other was." It was a moment emblematic of the healer New Yorkers hoped Dinkins would be when they elected him over U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani in 1989, shortly after young whites in Brooklyn's Bensonhurst section murdered Yusef Hawkins, a black youth who had wandered onto their turf to look at a used car. It was emblematic, too, of the promise of black "Rainbow" mayoralties in multiracial cities in the 1970s and 1980s—Tom Bradley in Los Angeles, Harold Washington in Chicago and Wilson Goode in Philadelphia, to name a few.

Yet, just as those other rainbows have faded, the ecumenical side of Dinkins on display in Jerusalem has been eclipsed in the years since his "Vote your hopes, not your fears" victory four years ago. Challenged by Giuliani again this year, Dinkins has been reduced in part to running a "Vote your fears" campaign. A string of recent public claims by Dinkins supporters that Giuliani is backed by the Ku Klux Klan, fascists and Reaganites (although conservatives such as William Bennett and Pat Buchanan denounce Giuliani as a liberal) may coax some voters back into Dinkins' corner. But a victory at this price would hardly repeat the harmonic convergence that was once the rationale for a Dinkins candidacy.

What went wrong? There are two reasons for the decay of Dinkins's rainbow politics, neither peculiar to New York. First, a deep recession and economic upheaval demand a "reinventing" of local government that seems utterly beyond the reach of a mayor whose political style is more common in Europe than in America: that of a social-democratic wheelhorse. Dinkins's failure to articulate a rationale for municipal restructuring, much less attempt it against union and black clubhouse opposition, is one reason his government is torn by racial and other subgroup squabbling over jobs, entitlements and preferments.

Second, Dinkins's failures of leadership during a long, black boycott of Korean stores and amid black rioting against Hasidic Jews in Crown Heights are only the best-known of many abdications to the politics of victimization (among them his year-long delay of a contract for street toilets in deference to activists' demands that each one be wheelchair accessible). Such muddlings highlight the rainbow ideology's tendency to deepen racial and other differences in the name of respecting them; in the zero-sum game of urban governance, identity politics implodes.

Meanwhile Giuliani, the erstwhile altar boy with a Savonarola streak and a mostly-white inner circle, has created a Republican-liberal "fusion" slate, with Herman Badillo, the city's most distinguished Hispanic politician, running for comptroller. They claim they want to subordinate parochial grievances to a single, uniform civic standard. Alluding to the Korean boycott, Giuliani says he wants to convince blacks that "If I were mayor and some Italian-Americans were intimidating a black shopkeeper, I'd come down on them hard and fast. People have to be able to feel confident that they'll be protected, whatever the mayor's color."

It's a familiar pattern. Beyond New York, the Rainbow habit of crying racism has found itself discounted by voters of all colors who want better governance and less rhetoric. Politically centrist mayoral candidates, many of them, ironically, white men, have drawn substantial numbers of nonwhite voters into new coalitions—call them Rainbow II—by touting a can-do pragmatism and a common civic identity that is more than the sum of skin tones, genders, sexual orientations and resentments. The truth they've grasped remains obscure only to some in liberal Democratic circles and the academy: The more genuinely multicultural and racially diverse a city becomes, the less "liberal" it is in the Rainbow I sense of the term.

The pattern emerges from half a dozen donnybrooks of the past three years, including Houston and Philadelphia in 1991 and Los Angeles and Jersey City in 1992. In each, the liberal candidate, usually a person of color, had the mantle of the civil rights movement, the support of a multiracial, multicultural coalition and the endorsement of Jesse Jackson. He was militantly pro-choice, anti-death penalty and in favor of the most expansive gay rights and immigrant rights agendas around. He was applauded in black churches and endorsed by liberal newspapers. He may not have had much of an economic program, but he branded his white male opponent a closet Reaganite and sounded the trumpet for "progressive" unity.

The white male opponent, who typically had never held elective office, posed as a businesslike reformer, promising to clean house and create new jobs through commercial deregulation, better public safety, less onerous taxation and tougher union contracts. Preaching tolerance rather than correctness and touting endorsements from prominent Latinos and other minority leaders who had broken with the civil rights establishment, he vowed to unite the city across racial and partisan lines.

Closer examination turns up telling ironies. In Chicago's 1989 special election to fill out the late Harold Washington's term, Richard M. Daley, a son of--but also a reformer of--his father's infamous machine, trounced alderman Timothy Evans, who claimed the mantle of Washington's paradigmatic Rainbow I coalition and was backed enthusiastically by Jackson. Two years later, against a black former judge running on the Harold Washington party line, Daley carried 80 percent of the city's small but critical Latino vote and 26 percent of the black vote (up from just 7 percent in 1989).

Similarly, in Houston in 1991 Robert Lanier, a wealthy white real estate developer and native New Yorker, took 70 percent of the Latino vote to defeat Sylvester Turner, a black, Harvard-educated state legislator backed solidly by blacks and white Rainbow I liberals tied to former Mayor Kathy Whitmire. The popular Lanier--the first candidate in twenty years to be elected mayor with virtually no support from the 25 percent of the city's electorate that is black—is a shoo-in this fall for another two-year term.

That same year in Philadelphia, Edward Rendell, a Jewish New York native and, like Giuliani, a tough-talking ex-prosecutor, won the mayoralty by preaching fiscal austerity and municipal restructuring in a city facing bankruptcy. Campaigning energetically in the black community, he took 20 percent of the black vote against three black Democratic primary opponents before trouncing a Republican to succeed Philadelphia's first black mayor, Wilson Goode.

In July of this year, Los Angeles's Richard Riordan, another native New Yorker and a Wall Street investor, succeeded five-termer Bradley in the 58 percent non-white city by carrying 43 percent of the Latino vote, 31 percent of the Asian American vote, 14 percent of the black vote and 67 percent of the white vote against Rainbow I Democrat Michael Woo, a councilman who had led the opposition against Police Chief Daryl Gates. Riordan's Rainbow II is embryonic, at best, however: 72 percent of those who voted in the election were white. He has responded with high-level appointments of blacks, Latinos, Asians and gays.

Across the continent in Jersey City, both mayoral finalists this spring were white, yet the Rainbow II scenario was otherwise unchanged. Republican Wall Street investor Bret Schundler, yet another ex-New Yorker, beat a Jackson-backed Democrat by winning 40 percent of the black vote and 60 percent of the Latino vote in that majority nonwhite city. This, even after Jackson warned in radio spots that his candidate represented "the values of the USA—the United States of America," while a vote for Schundler was a vote for "the values of the USA--the Union of South Africa."

It was, of course, nothing of the kind. Neither was Daley's victory in Chicago—which Jackson tried to prevent by linking Daley to his father's infamous "shoot to kill" order against arsonists in 1968—simply a white racist restoration. The new mayors have won by tapping a growing disillusionment with old-style "civil rights" politics among voters whom the movement has betrayed, and by including new racial minorities who feel excluded by black-led Rainbow I administrations.

The new mayors depart, respectfully but firmly, from the politics of such trailblazing black mayors as Gary, Indiana's Richard Hatcher, Cleveland's Carl Stokes, Atlanta's Maynard Jackson, Detroit's Coleman Young, New Orleans's Ernest "Dutch" Morial, Chicago's Harold Washington and the District of Columbia's Marion Barry. Most of these men were broad-shouldered veterans of elemental, often brutal struggles for racial justice that had honed their leadership qualities and introduced them to class- as well as race-consciousness. Most won narrowly against unyielding white hostility.

In office, they had to outmaneuver scheming white politicians, censorious editorial boards and rebellious subordinates in heavily white municipal work forces. With rhetoric, if not redress, they had to relieve the pent-up frustrations of blacks long exiled from city politics and jobs. Civic elites demanded that they end black crime. Businessmen, taking advantage of the mayors' desperation about economic decay, co-opted them into "big bang" development schemes that siphoned city resources from poor neighborhoods. Detroit's Young became defensive and bitter, Marion Barry dissolute and corrupt. Harold Washington seemed to thrive on frustration, towering over his more parochial black supporters and white adversaries alike, but he died in office. Literally and figuratively, the hearts of black mayors were broken by their divided cities.

At the same time, though, some black trailblazers and their Rainbow I successors have shifted from protecting basic individual rights and mobilizing economic coalitions to touting racial group rights and policies that are gratuitously destructive of traditional families. It's almost as if Rainbow I administrations simply presume, and so accelerate, civic and social balkanization. They often pit blacks against almost everyone else, not just against declining white electorates.

It is here, in the interaction of shifting civil rights strategies and changing urban demographics, that Rainbow I meets its end. In the years after 1970, 10 million immigrants, the vast majority of them nonwhite, entered American cities. Today, 40 percent of Angelenos and 30 percent of New Yorkers are foreign-born. These Mexican and Filipino laborers, Chinese and Puerto Rican seamstresses, Pakistani and Haitian cabbies and Korean and Dominican merchants often bring with them notions of race that are more fluid and ecumenical than those of American blacks or whites. They don't necessarily embrace a Rainbow I agenda of affirmative action and group rights-oriented litigation that presumes victimization by white racism. They rely more heavily on family and communal ties in order to achieve success.

For example, the immigrants of color in New York City's poorest census tracts are three times more likely than their American black and Puerto Rican neighbors to live in two-parent households. They're more likely to work within ethnic niches of the economy and to favor public spending on police and schools rather than on welfare, foster care, homeless shelters and drug treatment. The median incomes of Caribbean blacks and Asian Indians exceed those of American blacks, blunting charges of institutional racism. Chinese and Mexican immigrants' incomes are lower, but their family structures and values point upward. Even the high level of welfare dependency among Soviet refugees only underscores that culture, not racism, is the key variable in urban success.

Polls and voting patterns suggest that most newcomers are wary of the stigma and polarization that often accompany race-based politics and programs such as all-black schools, racial districting, municipal affirmative action quotas and multicultural curricula. In recent New York City school board elections, ten of thirteen Asian candidates, and half of the Hispanic candidates, ran against a liberal "Children of the Rainbow" curriculum, backed by Dinkins, and Giuliani has sometimes led Dinkins in polls of Asians and Latinos.

The future is visible in an editorial in San Diego's Mexican-American newspaper La Prensa, cited recently by Jack Miles in The Atlantic, that heralds Latinos as the new "bridge between blacks, whites, Asians and Latinos. They [Latinos] will have to bring an end to class, color and ethnic warfare. To succeed, they will have to do what the blacks failed to do: incorporate all into the human race and exclude no one."

Demographic change is also accelerating Rainbow I's passing by diminishing black clout. Latinos, vital to Rainbow II victories, now outnumber blacks in Los Angeles and will do so in New York, Houston and Jersey City by the next census. Latinos have long outnumbered blacks in such Sunbelt and Western cities as Miami, San Antonio and Denver; the last two elected Henry Cisneros and Federico Pena, both now in Clinton's Cabinet, an honor shared by no former black mayor. The risk is that the new, multiracial coalitions will be openly anti-black.

Yet Rainbow II politics are by no means off-limits to black mayors, who do well among whites when they abandon a Rainbow I agenda. In 1989 Cleveland's Michael White became Rainbow II's first prominent black mayoral standard-bearer after defeating a "blacker-than-thou" opponent; he is a shoo-in for re-election next month. Denver and Seattle, both about 70 percent white, elected Wellington Webb and Norman Rice, black mayors who defy Rainbow I stereotypes. Both practice fiscal conservatism and reject race-based politics. Similarly, Chester Jenkins, the black mayor of mostly white Durham, North Carolina, credits Jesse Jackson with energizing black voters, but, describing his own campaign, says, "I didn't speak of a rainbow coalition. I'm sure that turns a lot of white people off. People think that when a black person is running, he is going to be a big taxer and spender. I'm not that way." Even in heavily black cities, where the first black mayors have left the field to black candidates hawking everything from nationalist paranoia to race-neutral economic realism, debate is less often foreclosed by charges that any candidate's views are racist.

But it's one thing for Rainbow II mayors to win by arguing that the poor, who want to live decently, and the middle class, which wants to live safely, have a common interest in restructuring government. Actually shifting government's emphasis from bureaucratic compassion to urban reconstruction is harder. A disabled federal government—the legacy of Reaganomics—forces mayors to choose between aiding today's casualties and making investments that might prevent more casualties tomorrow.

There's a flawed Democratic legacy at work here, too: In the 1960s, Great Society funding drove cities to increase the social welfare portions of their budgets from around 15 percent to as much as 30 percent. Today, most cities can't meet their needs merely through tough bargaining, more productivity and privatization. The choices mayors face do follow racial fault lines, imperiling efforts to put civic-consciousness above race-consciousness.

One who seems undaunted by these risks is Edward Rendell, the new mayor of Philadelphia. A city of 1.6 million people, it is about half white, 40 percent black and 6 percent Latino. A son of Manhattan's West Side with a voice like Mel Brooks, he moved to Philadelphia to attend the University of Pennsylvania and served as district attorney before winning the mayoralty in 1991.

The city had become insolvent in the late 1980s under its first black mayor, Wilson Goode. Its bonds had been downgraded, it was borrowing at credit card rates and it was running a structural deficit amounting to 10 percent of its $2.3 billion budget, owing to the collapse of its manufacturing base, federal cutbacks and generous union contracts. Goode, a stiff Wharton manager and a passive subscriber to Rainbow I nostrums, had alienated blacks as well as whites while deferring necessary reforms. His infamous bombing of move headquarters in 1985, which destroyed a block of residential homes, was only a symptom of his lack of command.

With Goode retiring, Rendell decided to run against three black Democratic candidates by presenting himself as a "New Democrat," an apostle of David Osborne's and Ted Gaebler's Reinventing Government. When the candidates were asked whether they would accept a strike of city workers if it was necessary to turn the city around, "the other three hemmed and hawed," Rendell recalled in an interview with Newsday. "I looked in the camera and said, `I hope it doesn't become necessary, but there's a decent chance it will. The answer to your question is yes. I don't want a strike, but if a strike's necessary to bring about the type of changes we need, then I'm ready.'" Rendell's strong personality and the city's desperate straits made the election a referendum on whether Philadelphia could look beyond color for candor about its condition.

Rendell could promise not to roll back blacks' political gains relative to whites' because, thanks to enlightened civil service reforms in the '50s, Philadelphia had long had a municipal work force as black as its population. As early as 1964, its police department had been 22 percent black, while nearby Newark and Detroit were at 5 percent. Equally important, Philadelphia has a 20-year-old black political establishment that predated Goode and doesn't countenance the superheated racial rhetoric common in New York or Detroit. Rendell won an absolute majority in a four-way primary, carrying 20 percent of the black vote against his black opponents. "It's not that the era of the black mayor is over," he reflected, "The era of blacks voting lockstep for black candidates is over."

In office, Rendell forged an alliance with newly elected City Council President John Street. "He handled the transition very smoothly, made deals with the black political leadership," comments Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Acel Moore. The city's mayors often have been at loggerheads with its council for institutional, not racial, reasons. Rendell courted Street, giving him an implicit veto on some initiatives.

That meant giving ground on privatization--keeping the new convention center under city management, for example, lest black jobs be lost. Yet Rendell privatized custodial services, prison health services and other functions, and says that similar initiatives will soon save $40 million. He insists that all whose jobs are privatized can be hired by other agencies or private contractors. But the contractors impose steep pay and benefit cuts, the point of privatization being to save money at workers' expense. And, as recent New York City scandals involving asbestos removal and parking ticket collections show, privatization can bring corruption and incompetence. Rendell counters that most city unions can avoid such troubles by changing their own work rules to improve productivity.

Rendell and Street also scaled back, by roughly $100 million, a fat trash collection contract negotiated by Goode. That meant weathering the feared strike. When union leaders cried that "an administration of white guys in suits" was beating up on black employees, the new mayor challenged black voters: "Do you get twenty paid sick days on your job? Do you get fourteen paid holidays?" The strike lasted less than a day after Rendell gave union leaders face-saving exits.

Philadelphia is still a city in decline. Its large public housing authority, which shelters 10 percent of the populace, is mired in patronage and corruption. Its industrial areas are in ruins. Its tax structure is a mess. But Rendell is at least candid about his city's options. Rainbow I mayors like Goode (and, notably, Dinkins) tend to live in denial, railing at Washington without seriously rethinking their own emphasis on rights and redistributive services. Rendell argues that mayors who want a new federal urban policy will have credibility "only if we come to Washington with clean hands."

Rendell is not the only Rainbow II trailblazer. In Cleveland, Michael White, a self-described street fighter from the city's tough East Side, combines an "attitude" toward powerful elites with a fierce determination to reinforce conservative social values in a distinctively black idiom. He ran for mayor in 1989 as a maverick state senator and won partly on a fluke: the two white candidates in the primary were so equally matched that they canceled out each other, and White squeaked past them into a runoff with the most powerful black politician in town, City Council President George Forbes. For the first time, Cleveland's electorate, half black, half white, faced a choice between two blacks.

White had made the runoff partly on his own steam, too, with a forceful campaign against black crime, school busing and Forbes's penchant for playing the race card, which had enraged many whites. "White articulated a vision and said the same thing on both sides of town," says Plain Dealer columnist Brent Larkin. He argued that blacks who opposed busing didn't have to fear saying so just because whites opposed it, too. In an ugly runoff with Forbes, White won with 30 percent of the black vote and 90 percent of the white vote--an inauspicious beginning for a black mayor by Rainbow I standards, but one he soon turned to his advantage among blacks.

Since the rocky reign of its first black mayor, Carl Stokes, in the late 1960s, Cleveland's population has dropped roughly 30 percent, to 505,000. Under a succession of white mayors, including ethnic populist Dennis Kucinich and corporate darling George Voinovich, Cleveland touted itself as a comeback city with a sleek new skyline and, not far off, a $365 million stadium for the Indians that will rival Baltimore's Camden Yards. But more than a third of Cleveland's population lives below the poverty line, and much of its East Side is an inner-city moonscape.

White has tackled some problems that his white predecessors avoided. Although he doesn't run the city's elected school board, he backed a winning, insurgent, biracial slate opposed to busing. He won give-backs, reduced overtime and one-cop patrol cars from city unions. He backed cops in crackhouse evictions and a controversial case involving the death in police custody of a drug-abusing black suspected of car theft.

White has been criticized by blacks and white liberals for these positions and for scolding Jesse Jackson at the 1992 Democratic National Convention in New York, when Jackson criticized Bill Clinton after his nomination was inevitable. White's obvious pride in being black has helped him on the East Side, but "he has consciously attempted not to be a `black' mayor," Larkin says. "If anything, he makes a conscious effort to be a mayor who happens to be black." Civil rights leaders may not like that, but Cleveland's voters do.

As White's and Rendell's accomplishments mirror one another, Rainbow II moves to the center of urban politics from both sides of the racial divide. This is nowhere more clear than in New York, where a Dinkins defeat would mark the first time that a big city's first black mayor has ever lost a re-election bid. Such a defeat, especially amid the liberal fear-mongering about racism and fascism now underway in New York, would be a telling repudiation of twenty years of misguided racial politics.

But a Giuliani victory would not settle the question of whether Rainbow II administrations can regenerate American cities as places where new products, ideas and people circulate freely across the lines of color and class. Full black participation in that exchange is what the early civil rights movement sought, and what more recent black attacks on the liberal civic culture have repelled. Can new mayors outflank or creatively redirect such assaults?

The challenge ought to be irresistible to Democrats, who bring to cities a sophistication at governing and a love of urbanity. But those who cling to Rainbow I social-welfare spending and identity politics will continue to default to Republican neophytes such as Los Angeles's Riordan, Jersey City's Schundler or, indeed, Giuliani. Only if Democrats follow the example of candidate Clinton, who spoke for those "who work hard and play by the rules," and who rebuffed that consummate Rainbow I phony, Sister Souljah, can they expect to win like Rendell and White. Only if Rainbow II succeeds will cities regain their promise and, not incidentally, nourish the occasional friendship where "one didn't know what the other was."