Five Who Fear the Future

April 16, 1956

“Progress is the railroad of Liberty," said Proudhon in 1853, using a 19th Century metaphor for a 19th Century thought, and few of his contemporaries would have contradicted him. The onrush of the Industrial Revolution, the spread of evolutionary doctrines in science and history, the messianism of current political theory, all suggested that humanity was proceeding steadily onward, perhaps towards perfection of social organization, perhaps even towards self-transcendence into a more-than-human excellence of character.

There were, indeed, some conservatives who looked with constitutional distrust upon the future, but these were a minority compared with the throng of devotees of Progress among whom the liberals of the Center were distinguished from the radicals of the Left mainly by a disagreement as to how Progress would take place—whether steadily and smoothly by what Sidney Webb once called “the inevitability of gradualness” or jerkily by revolutionary leaps similar to the biologist’s mutations, as Kropotkin suggested.

Today Proudhon’s railroad of Progress is suffering a remarkable decline of traffic. Its very name is suspect, and not only among Congressional Committees. A Parisian writer recently remarked to me that, up to the Thirties, the most popular name among French bistros was Bar du Progress, but that nowadays no tavern-keeper would think of using the name for a new establishment; he would be much more likely to call it Bar du Bon Vieux Temps. This attitude reaches far beyond the narrow world of Parisian barkeeps, and much of the significant criticism of the old faith in Progress and of the goals of that faith is coming from intellectuals, and particularly from the radical intelligentsia of Western Europe.

In techniques, goes the familiar argument, there has been an expansion of human powers beyond even the wildest Wellsian dream, but in politics and in human relations generally there seems to have been little advance and, in some important sectors, a dangerous retreat. It is the peril involved in this widening gap between technological complexity and moral stagnation that awakens so many fears, and these fears, it must be observed, did not originate with the atom bomb. The questioning of the dogma of Progress, the erosion of the Utopian vision, began among European writers 30 years before Hiroshima gave it an apocalyptic dimension.

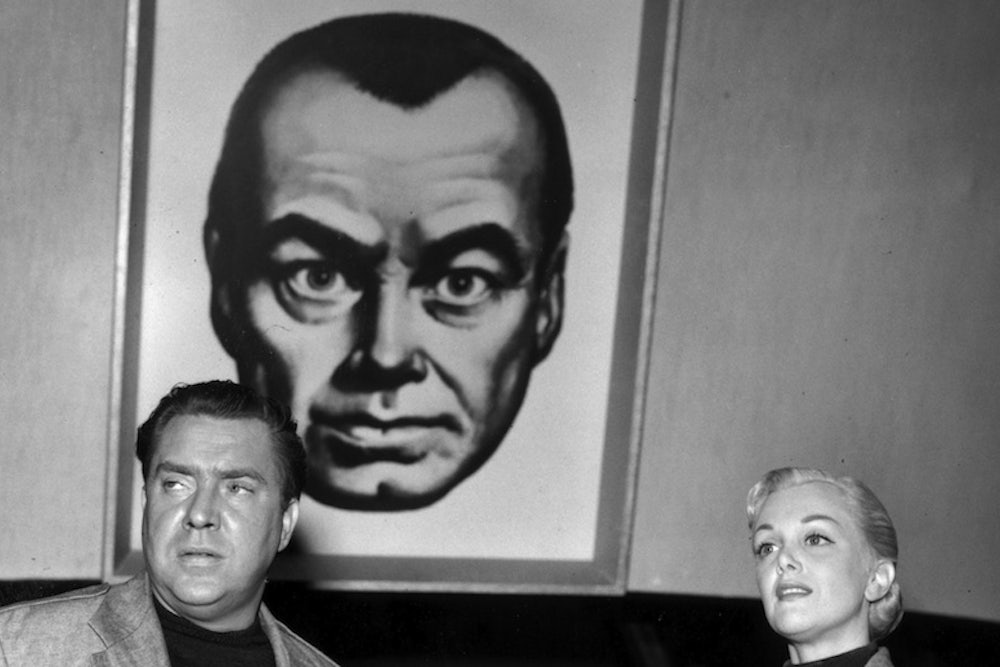

This negative movement of thought has grown so far that it is now possible for the literary critic to detect a whole trend of disillusionment with progressivist ideas, a trend which in the Anglo- Saxon world clusters around some of the most distinguished names of the half- century—Shaw and Wells, Huxley and Orwell and Koestler. Significantly, these writers were—and remained—men of the Left, with quite different standpoints from the conservatives who had hitherto condemned progressivist ideas on reactionary grounds; they have criticized world developments during the 20th Century, not for the changes that have been wrought in the old order, but because the old radical ideals of equality and freedom, far from being promoted, have been put in peril.

Here, however, some distinctions have to be drawn between the various writers I have mentioned. On the one hand, there are the anti-Utopians, Huxley and Orwell, who in reality are not quite so despairing as the pessimism of Brave New World and 1984 might at first suggest. On the other hand, there are the ex-Utopians, like Wells and Shaw in the recent past and Koestler in our own day, whose loss of hope, I suggest, is of a much more chronic kind.

I will comment first on the last group. All its members have held, in the earlier or middle parts of their careers as writers, some kind of Utopian faith, connected intimately with a breakdown of confidence in the efficacy of a democratic ideal founded on ordinary human beings. Fifty years ago, declaring that “Man will return to his idols, in spite of all movements and all revolutions, until his nature is changed,” Shaw constructed futurist fantasies about long-lived supermen; Wells, after his disillusionment with Fabian socialism, wrote two romances about elaborately organized “ideal” societies; Koestler, having lost faith in German liberalism, accepted for years that mirage of a perfect social order whichdedicated Communists substitute in their minds for the reality of the USSR. For all of these men the afflatus of Utopian dreaming was followed by the fall into a second disillusionment. For Shaw, this fall echoes in Saint John's last sorrowing cry, "O God, that madest this beautiful earth, when will it be ready to receive thy saints? How long, O Lord, how long?”, and deepens into the sterile political plays of his last years, until, a little while before his death, he declares, “since the dawn of history there has been no change in the natural political capacity of the human species.” For Wells, writing Mind at the End of its Tether in the gloomy end of his life, it reveals man at a perilous turning point of destiny. “Man must go steeply up or down,” he says, “and the odds seem to be all in favor of his going down and out.” And Koestler’s vision in his latest book, The Trail of the Dinosaur, is closely similar. “We shall either destroy ourselves,” he says, “or take to the stars.” And he gives no convincing reason to suppose that the latter event may materialize.

The despair of writers like these has its roots in the ideological pasts; the placing of hope in a superman of the future, in an imaginary commonwealth, in a Godlike party, already indicates a loss of faith in humanity as it is. The resources of ordinary men are condemned, and trust is places in the inhuman force of evolution of the impressionable rule of a plan constructed by an infallible élite. But once faith in man is lost, it is not easy to recover. Those who abandon the present for the future, and then lose confidence in the future, are almost doomed to end in pessimistic negation. For these men Proudhon’s railroad of Progress ends, not in Liberty, but in a desert where all they can do is to hope for a star. Nor are they merely isolated individuals. Instead, the resurgence of revivalist religion and the vast popularity of the otherworldly fantasies of science fiction writers are phenomena which suggest that men like Wells and Koestler are the intellectual spokesmen of a widespread feeling that, for man as he is, progress has come to an end and only the realm of miracles can offer a solution to his dilemmas.

But if the ex-Utopian represents modern liberal and radical pessimism reaching its extremity in the rejection of man as we have known him, the anti-Utopian presents a different picture, since he stands as the advocate of the human race against the distortion of progress; man is his hero, and man's defeat by the over-development of social and political organization is his tragedy. At first sight, indeed, both Brave New World and 1984 seem to present extraordinarily bleak views of our possible future. In both novels the Utopian society is so powerful that it can crush any spark of that spirit of freedom which the rulers recognize as the principal danger to their dominion, and so the rebellions against uniformity which provide the essential conflicts in both Brave New World and 1984 are efficiently defeated. Not only are they defeated, but they never have any real hope of success, since the net of conditioning has already grown so tight that only the sports and the freaks even think of resisting, and they can be dealt with easily by the forces of the all-molding state.

Yet we must bear in mind that the visions contained in both Brave New World and 1984 are clearly conditional. Huxley and Orwell do not say gloomily, like Wells and Koestler and Shaw, “Humanity is done for, unless a miracle lifts it towards the heavens.” Rather they suggest that, if certain tendencies towards regimentation which have appeared throughout the world are allowed to develop without hindrance, then we may within a foreseeable future find ourselves trapped in a world where freedom, and all the values that go with it, have withered and been forgotten. Huxley puts the argument well when he says:

Unless we choose to decentralize and to use applied science, not as the end to which human beings are to be made the means, but as the means to producing free individuals, we have only two alternatives to choose from: either a number of national, militarized totalitarianisms…or else one supranational totalitarianism … developing, under the need for efficiency and stability, into the welfare tyranny of Utopia.

Brave New World and 184 are therefore not pessimistic statements of almost certain doom like Mind at the End of Its Tether. They are rather parables of warning; they suggest, not that must quakingly hope for a mutational miracle, but that we have it in our hands, still at this late hour, to ward off the moral blindness that might reproduce the tragedies portrayed in their pages. Even Orwell, despite the apocalyptic terror that broods over 1984, did not see the catastrophe as inevitable; indeed, in an essay criticizing James Burn- ham's view of the future, written a little before 1984, he hinted that, even if the totalitarian nightmare came about, it need not necessarily be final:

The huge, invincible, everlasting slave empire of which Burnham appears to dream will not be established, or, if established, will not endure, because slavery is no longer a stable basis for human society.

Such a remark seems to indicate that the element of apocalyptic fable in 1984 is ore than it appears at first sight, and that Orwell overdrew the weakness of the human individual when confronted by the embattled state in order to make us aware of the possible extremity of the perils that confront us rather than of their probable actuality. Finally, the fact that Orwell and Huxley should have seen worlds without freedom in such ugly terms is not necessarily a measure of their despair; it is rather a measure of their hatred of un- freedom and their anxiety for the perpetuation of freedom itself and its attendant values. Because of this they may well be, among the many Cassandras of our age, those whose voices we should interpret with the greatest care. For, while their books imply a profound criticism of the facile 19th century idea that Progress is inevitable and that all kinds of progress are necessarily food, they are not anti-progressive in an absolute sense; they do not state, as Wells did, that “ordinary man is at the end of his tether.” Rather, they insist that changes in technology and in psychiatric methods must be subordinated to certain moral values which man has held for a long time, and that only by this perpetual ascendancy of the moral over the material will Progress in human societies be real.

For such a view of Progress, Proudhon’s metaphor of the railroad will no longer suffice. Perhaps it can better be likened to one of those pioneer settlements, blossoming on the edge of the waste land, where careful cultivators stand always ready to defend themselves from the enemies who wait in the desert beyond.