As soon as today’s decision on Noel Canning came out, conservatives were quick to try to portray the decision as the Supreme Court dropping “a huge bomb on the Obama administration,” that is far from the truth.

At stake in the case was not only whether the President could make recess appointment during short pro-forma Senate recesses that lasted three days but, more importantly, whether the President could make recess appointments during longer intrasession appointments. While the Court unanimously rejected the power of the president to make appointments during these pro forma recesses, the liberal majority rebuked the conservative attempt to strike down the president's power to make recess appointments during longer intrasession recesses.

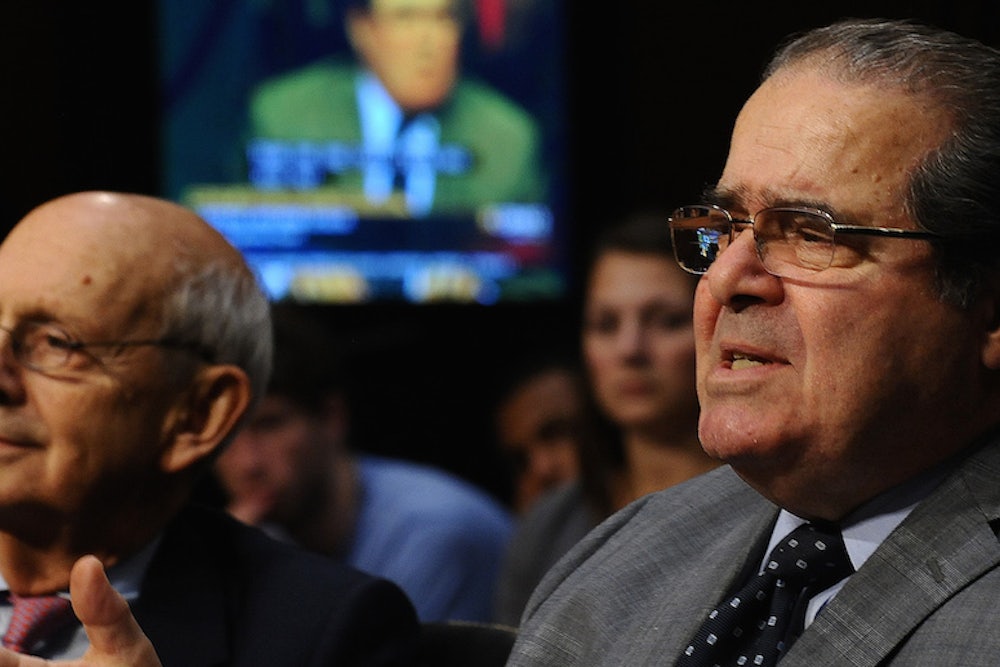

While conservatives may see this as a victory, Justice Scalia’s concurrence sounded much more like a sorrowful defeat. He notes that, “The Court’s decision transforms the recess-appointment power from a tool carefully designed to fill a narrow and specific need into a weapon to be wielded by future Presidents against future Senates.” Justice Scalia, writing for the conservative wing of the court, tried to argue for a far more limited Presidential power that would be confined only to making recess appointments between sessions of the Senate.

The case, beyond the recess appointments themselves, represents a liberal victory for a methodology of interpreting the Constitution as an evolving text that is rooted in historical practice. Justice Scalia, a believer in textualism without any modifications, bemoans how the Court “casts aside the plain, original meaning of the constitutional text in deference to late-arising historical practices that are ambiguous at best.” To the conservative wing of the court, they want analysis to start and end with a focus on the Constitution’s text and would prefer to avoid any discussion of the lived experience of the relationship between the President and the Congress. Scalia has said that he wished the idea of a ‘living constitution’ would “die” and his opinion reflects his dedication to Constitutional text, without any add-ons. Scalia has famously said he seeks to uphold a “dead Constitution.” While Justice Scalia grants that many Presidents had made recess appointments during sessions, he dismisses this history as nothing more than historical practice “well after the founding, often challenged, and never before blessed by this Court” and argues that it should be irrelevant.

It is fitting that Justice Breyer delivered the majority opinion, which preserved the President’s power to make intrasession recess appointments. While Justice Breyer has famously said that the court should not be composed of nine historians, he has been a proponent of the Supreme Court making decisions that are practical and accord with how the law works. Breyer’s tenure on the Court has been marked by his “pragmatic passion,” as Professor Paul Gewirtz termed it, and his attempt to understand how the Court’s decisions play out in the real world.

Rather than trying to slice and dice the ambiguous text in the Constitution, Justice Breyer’s opinion focuses on the evolution of historical practice of the President in making recess appointments. Breyer returns to James Madison for a vindication of this approach, Madison having written that; “was foreseen at the birth of the Constitution, that difficulties and differences of opinion might occasionally arise in expounding terms & phrases necessarily used in such a charter ... and that it might require a regular course of practice to liquidate & settle the meaning of some of them.” He cites a litany of opinions in which the Supreme Court has relied on historical practice to interpret the power of the President, such as Justice Frankfurter’s concurrence in the Steel Seizure case, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co v. Sawyer.

In the end, the Obama administration lost on the specific question of the pro forma three-day recesses. Justice Breyer argued that “the pro forma sessions count as sessions, not as periods of recess” and therefore the President cannot use them to make recess appointments.

In the ongoing debate on Constitutional interpretation between Justice Breyer and Justice Scalia, representing in some ways the liberal and conservative visions for Constitutional interpretation, this was a victory for a method of Constitutional interpretation that is willing to account for historical practice and the lived reality of the law in construing the Constitution. Breyer concludes his opinion by noting that “the Clause’s text, standing alone, is ambiguous” but that a “broader reading” that is “reinforced by centuries of history, which we are hesitant to disturb” guides the Court towards upholding the President’s power to make recess appointments during a recess, whether it is intrasession or intersession, that is long enough.

Despite the hype around this case as a rebuke of the Obama administration, it is in large part an important victory for pragmatism at the Supreme Court. Obama and future Presidents will find a way to make recess appointments without using pro forma recesses and future Justices will be left with an important precedent favoring the utilization of history and lived experience in shaping the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution.