Attorney General Eric Holder's recent resignation announcement prompted a flurry of assessments on his six years of service under President Obama. He let Wall Street off too easy. He was a hero to the poor. He compromised civil liberties in the name of national security—and defended civil rights better than any attorney general before him. But the debate over Holder’s record has overlooked one of the most important aspects of his legacy. Holder has been profoundly at odds with the rest of the Western world on one of the most significant human rights issues of our time: the death penalty.

All Western democracies except America have abolished capital punishment and consider it an inherent human rights violation. America further stands out as one of the countries that execute the most people. Thirty-nine prisoners were executed by the United States in 2013. While that figure marked a continuing decline in the annual number of U.S. executions, it still placed America fifth worldwide, right behind several authoritarian regimes: China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia.

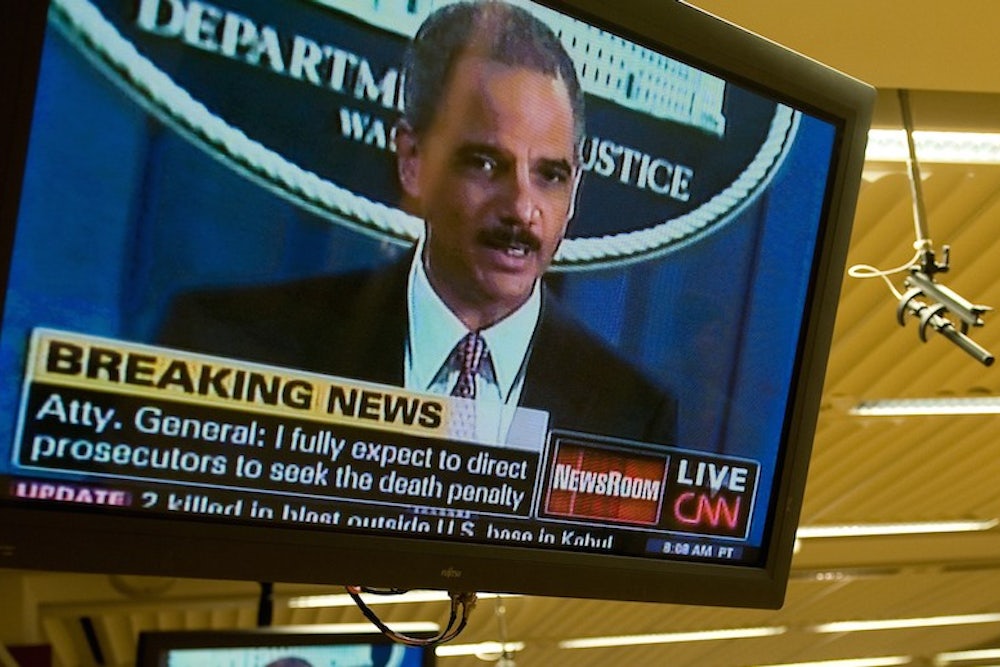

No federal prisoner has been executed since 2003, yet Holder’s decisions could ultimately lead this de facto moratorium to end, as he authorized federal prosecutors to pursue capital punishment in several dozen cases. "Even though I am personally opposed to the death penalty, as Attorney General I have to enforce federal law," Holder has argued. Prosecutors actually have the discretion not to pursue the death penalty at all—at the risk of losing popularity—since enforcing the law does not require pursuing capital punishment as opposed to incarceration. In fact, many police chiefs consider the death penalty counter-productive because capital cases require extensive time and resources, and distract government officials from focusing on “real solutions” to crime.

Holder notably approved the decision to seek the death penalty in the federal trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who is accused of perpetrating the Boston Marathon bombings of 2013—and whom a majority of Americans want to be executed. Nevertheless, the state of Massachusetts has abolished the death penalty and only 33 percent of Boston residents support executing Tsarnaev as opposed to sentencing him to life in prison without parole. However, Holder’s decisions supporting capital punishment have hardly been limited to terrorism cases. For example, he authorized the recent decision to seek the death penalty for Jessie Con-Ui, a Pennsylvania prisoner accused of murdering a federal correctional officer.

Many American politicians, including Obama, have argued that they support the death penalty in principle but are concerned by problems with its administration, such as racial bias, the risk of executing innocents, the financial cost of capital cases, and the death penalty’s lack of deterrent value. Holder’s statements expressing reservations about the death penalty have similarly focused on procedural problems like “miscarriages of justice” due to the wrongful conviction of innocents. While opposition to capital punishment is growing among the U.S. public, it is largely rooted in these procedural concerns.

The death penalty is rarely framed as a human rights issue in America, unlike in other Western democracies. That's partly because the principle of human rights plays a very limited role overall in the legal and political debate in the U.S., where "human rights" commonly evoke foreign problems like abuses in Third World dictatorships—not problems at home.

The situation is different on the other side of the Atlantic, where the European Court of Human Rights tackles a broad range of problems facing European states, from freedom of speech to labor rights, discrimination, and criminal justice reform. National human rights commissions also exist in multiple countries, including Australia, Denmark, France, Germany, and New Zealand. These bodies focus mostly or exclusively on monitoring domestic compliance with human rights standards. On the other hand, the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission, an arm of the U.S. Congress, focuses on the human rights records of foreign countries.

The relative absence of human rights as a principle in modern America is remarkable given how U.S. leaders actively promoted the concept in its infancy. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt invoked “human rights” in his “Four Freedoms Speech” of 1941. Eleanor Roosevelt was among the architects of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. As the human rights movement progressed in later decades, Martin Luther King said in 1968 that “we have moved from the era of civil rights to the era of human rights.”

Even though Holder regards King as one of his models—and despite his proposals to make the U.S. penal system less punitive and discriminatory—the nation’s first black attorney general hardly put human rights at the center of his agenda.

The death penalty is far from the only human right issue where America stands apart from other Western democracies. America effectively has the world’s top incarceration rate,1 with 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prisoners. America is likewise virtually alone worldwide in authorizing life imprisonment for juveniles. Its reliance on extremely lengthy periods of solitary confinement has been denounced by the U.N. Special Rapporteur on Torture. The extreme punishments regularly meted to U.S. prisoners are generally considered flagrant human rights violations in other Western countries. Nevertheless, Holder argued that America has “the greatest justice system the world has ever known.”

By the same token, no other modern Western democracy has gone as far as America in disregarding international human rights standards as part of anti-terrorism measures. This trend has been epitomized by indefinite detention at Guantanamo and the torture of alleged terrorists under the Bush administration. These practices have sharply divided U.S. public opinion but only a segment of Americans have depicted them as “human rights” abuses. For example, numerous Americans have emphasized that torture is ineffective and tarnishes America’s reputation. However,such utilitarian concerns do not necessarily imply that torture is an inherent human right violation.

The relative absence of “human rights” as a principle in modern U.S. law should not obscure America’s long tradition of freedom of speech and religion. And some states are more progressive than others. Michigan and Wisconsin, for instance, abolished the death penalty in 1846 and 1853, respectively. A dozen states have been among the world’s trailblazing jurisdictions with regard to same-sex marriage and other gay rights.

Still, the limited weight of human rights in the U.S. legal and political debate is not without consequences. Human rights are a far stronger basis to oppose practices like the death penalty or torture than the administrative arguments frequently invoked in America. The human rights argument against such practices is largely based on the premise that they violate human dignity. Illustratively, the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)—a major international treaty—states that the "abolition of the death penalty contributes to enhancement of human dignity and progressive development of human rights." If one accepts that premise, it is no longer relevant to assess whether capital punishment or torture are implemented “fairly” or “effectively.”

The protocol of the ICCPR committing countries to abolish capital punishment has been ratified by 81 nations so far. America is the sole Western democracy that has refused to do so. Overall, two-thirds of all countries worldwide have now abolished the death penalty in law or practice, a trend influenced by the growing global recognition of capital punishment as a human rights issue.

Holder's narrow focus on problems with the administration of capital punishment suggests that he is among the many U.S. public officials and reformers who believe they have no duty to assess the “moral” issues regarding the death penalty. Whether this stance is justified or not, it seems quite exceptionally American in the modern Western world. Most contemporary European, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealander jurists probably would disagree with the notion that it is not their duty to assess whether executions violate human dignity.

Martin Luther King, who considered the death penalty an affront to human dignity, argued that “a genuine leader is not a searcher for consensus but a molder of consensus.” Perhaps Eric Holder—and his boss, Barack Obama—would have been willing to argue that the death penalty is dehumanizing if they did not fear losing popularity.

As of late, the Seychelles have technically surpassed America as the country with the highest incarceration rate. But since this statistic measures the number of prisoners per 100,000 people and the overall population of the Seychelles is barely 90,000 people, that signifies they have roughly 800 prisoners in total compared to over 2.2 million in America. Besides, America regards itself as “the leader of the free world,” whereas the Seychelles are a tiny archipelago with a questionable human rights record.