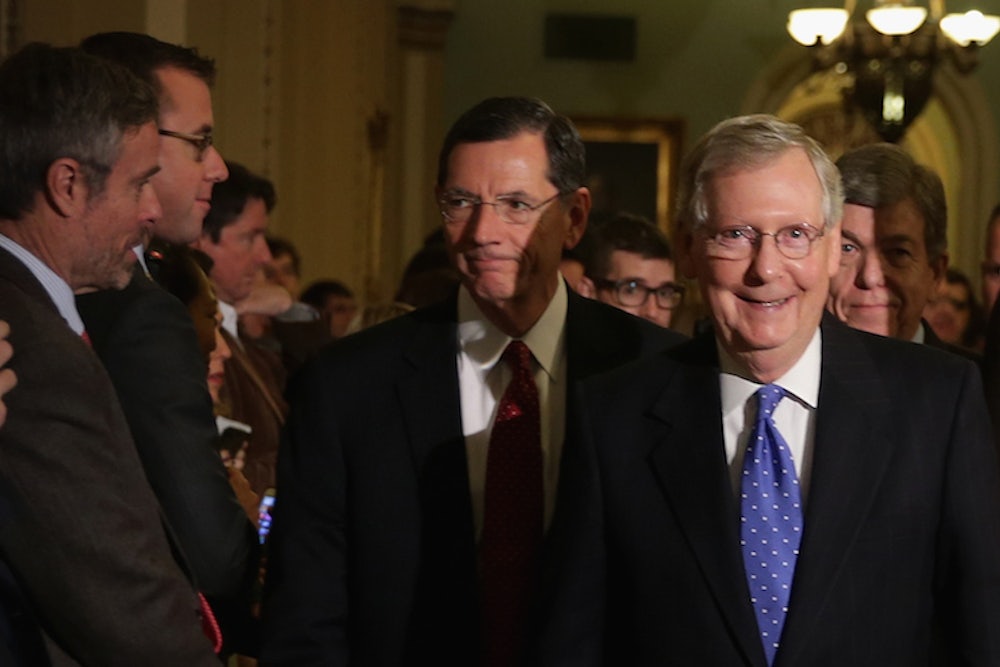

Several commenters, including The New Republic's Danny Vinik, have made light of Mitch McConnell’s recently renewed pledge to hold a test vote on repealing Obamacare when he takes over as Senate majority leader in January.

In the same interview, though, he also renewed his commitment to eschewing one of outgoing Majority Leader Harry Reid’s signature tactics, which he's used to protect Democrats from having to vote on politically contentious poison pill amendments, sponsored by Republicans. The parliamentary procedure is slightly arcane, but the strategic rationale is pretty straightforward.

For the past four years, with control of the House in Republican hands, Democrats have had to content themselves with using the Senate as a staging ground for votes on legislation they, the public, and sometimes even Republicans, broadly support. President Obama would have signed this legislation if it ever reached his desk. But since the House has stood in the way, the value to Senate Democrats has been purely symbolic. And to deny Democrats even symbolic victories, Senate Republicans have flooded each legislative debate with amendments—some pertinent, some absurd—that Democrats didn’t want to vote on, or that threatened the legislative coalition behind the underlying bill. When Reid has stepped in to protect his members from these votes, McConnell has used it as a pretext to filibuster.

With McConnell coming into control of the Senate, the dynamic will now flip. Most of his priorities won’t be Obama’s priorities. If McConnell wants to test Obama, he needs to send bills to the White House for signature or veto. He can’t send Obama bills without Democratic votes to beat back filibusters. And he can’t get those votes if he bottles up their amendments. Thus his promise to open up the Senate.

But in the interview, McConnell offered up a fresh rationale for making limited use of this particular power.

"The notion that protecting all of your members from votes is a good idea politically, I think, has been pretty much disproved by the recent election,” he said.

McConnell’s construction here employs a common post hoc fallacy. Democrats used this tactic. Democrats lost. Ergo it’s not a winning tactic. But another, non-fallacious way to make the same point is to say that there’s more to politics than dodging votes on poison pill amendments designed to generate 30-second TV ads. Avoiding them doesn’t save seats, and voting on them probably isn’t as dangerous to incumbents as the consultant class believes. And so he won’t stand in the way of them at all costs.

I don’t know how firmly McConnell believes this, or if he plans to follow through. Republicans have overstated Reid’s dependence on this maneuver to explain away their own, far more excessive abuse of the filibuster. The election allows McConnell to claim his critique of Reid’s leadership has been vindicated. And pretty soon vulnerable Republican incumbents like Kelly Ayotte and Rob Portman will be asking McConnell to shield them from tough votes themselves.

But I hope McConnell sticks to his guns on this one, because he’s completely correct about it. And if there’s a reason to think he will, it’s that it’s entirely consistent with his other, profound insights about the basic nature of legislative politics in America.

It really is true that too much business in Congress is determined by whether members are willing to take politically motivated messaging votes. Thus, other members—particularly in the minority—deploy messaging votes whenever they don’t like said business. My favorite example of this was when Senator Tom Coburn tried to derail health care reform in 2010 by introducing an amendment that would've prohibited exchange health plans from providing Viagra and other erectile dysfunction to convicted sex offenders. As it happens, Democrats were determined enough to pass Obamacare to vote down many of these kinds of amendments. But the threat of similar, less outrageous poison pills has deterred them from pursuing lower priority legislation in the Senate since they lost the House in 2011.

I think McConnell's probably right that these kinds of votes don't actually matter, just like he's right that most things in politics don’t turn on legislative minutiae, but rather on larger trends like economic performance and public perception of the president—which, it turns out, will be harmed more if he’s vetoing lots of popular-sounding legislation than if Dems are just blocking McConnell at every turn. McConnell wouldn't choose a more genteel legislative strategy if it weren't in his interest. But if he can prove that taking hard votes like this doesn't actually make much of a difference politically, then he can prove that the amendments themselves are worthless, or at least not to be feared, and perhaps make Congress a less ridiculous place in the long run.