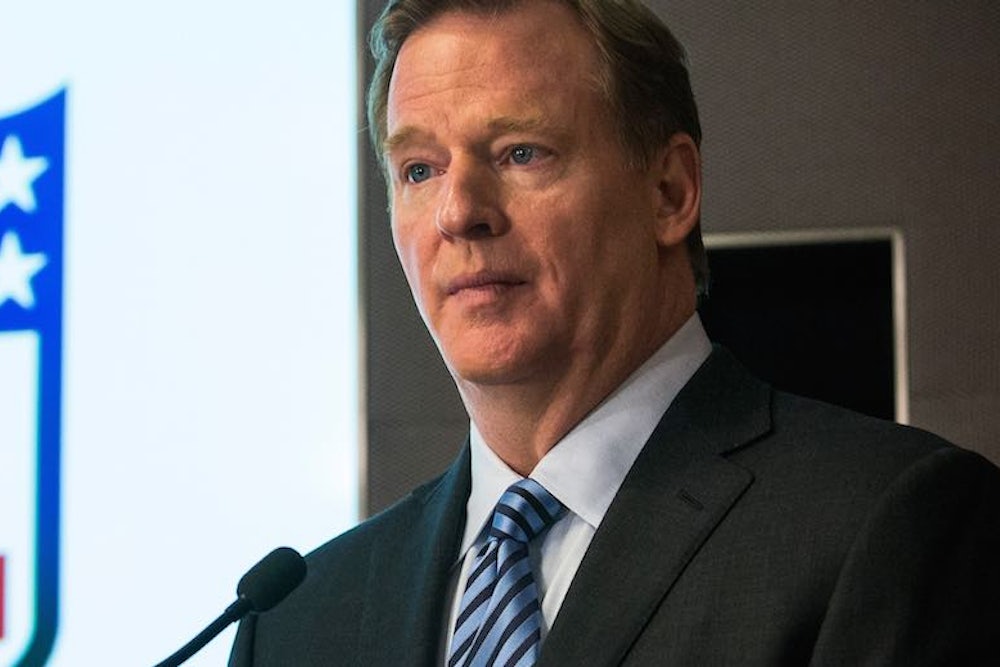

Just a few months ago, the "worst year in sports" was almost assuredly Roger Goodell's to lose. The NFL's commissioner, largely viewed as the tinpot dictator of a league that raked in about $9 billion last year, earned the ignominy after he'd issued two tone-deaf player punishments: the exceedingly harsh full-year suspension for Josh Gordon's ever-so-barely positive marijuana test, and the meager penalty for Ray Rice having KO'd his fiancée in a casino elevator. The Solomonic commissioner watched security video of the 212-pound Baltimore running back lugging Janay Palmer's limp body out of an elevator, then he decided to halve the punishment he gave to Gordon for going one toke over the line, then he split it again, and a third time: Rice was to rest for two games to begin the NFL season.

Then, in early September, TMZ published a second piece of video, showing the inside of the elevator where Rice clobbered Palmer. The vividness and the brutality repulsed. The commissioner couldn't adequately explain why he apparently hadn't seen the video, whether he'd tried to get it from the casino, and whether he'd tried to get it from police. As the outrage crested, the league quickly multiplied Rice's suspension to a full year, without being able to make clear why it had not done so earlier, despite indisputable evidence that such an attack had taken place.

A lesser man than Goodell might not have held his job through the subsequent maelstrom. (And a better man might have resigned.) Commentators called for Goodell's head; at least one, ESPN's Bill Simmons, was suspended for an indignant tirade demanding Goodell's firing. Another NFL star, Adrian Peterson, was arrested for whipping his 4-year-old child. The league office was coming off as a bastion of lies and of indifference to domestic abuse. Its players, increasingly, were looking like people whose jerseys you didn't want to wear in public. And through it all, the Washington Redskins were still calling themselves the Redskins, insisting ever more defiantly that the slur they'd adopted isn't offensive.

People said they'd had it with the NFL. Some fans proclaimed that they'd ignore football this fall, while polls showed a majority of Americans favored sponsors dropping the league for the season, if not permanently. The hashtag #BoycottNFL trend, and an anti-violence group hired a plane to drag a banner reading #GoodellMustGo over MetLife Stadium before a Giants game. The timing of the Rice contretemps happened to correspond favorably with the release of the hardback fan manifesto Against Football: One Fan's Reluctant Manifesto by author Steve Almond, who ripped the league for its cavalier celebrations of violence, for its greed, for its homophobia.

What came of all this pearl-clutching? Well, once the season fired up, not much. In fact, 2014 was the year we learned that no matter what scandals befall individual players or even the front office of the country's most powerful sports league, fans don't really care—at least, not enough to stop watching football. Americans were mad as hell, right until the Monday Night Football theme, that testosterone lullaby, coaxed them back onto the couch.

At Sports Illustrated, media reporter Richard Deitsch noticed the trend midseason. Ratings dipped a smidge for some league broadcasts, but most kept adding viewers. Pro football games weren't just the most-watched cable shows—they were some of the most-watched cable shows ever. When the Cowboys and, yep, Redskins went to overtime on one Monday night, viewership peaked at 22.5 million, a figure that Deitsch wrote qualified as the ninth most-viewed cable broadcast in history, outside of breaking news.

What happened here? Why couldn't America wean itself off the NFL, if only for a hot minute? For starters, it seems no one was ever much counting on a sports league predicated on people smashing the hell out of each other to comport itself as a model of rectitude on matters of violence. More than 4,500 retired players have sued the league, claiming that the NFL, as Patrick Hruby put it in the Atlantic, "downplayed, dismissed, and covered up the long-term neurological harm associated with football-induced concussions and hits to the head." The dementia, the depression, the suicides—all are being understood better in recent years in part because the NFL stopped resisting the obvious, not that the public at large ever fretted much. The NFL's denials don't offend most fans, who have been nursing their own denial for as long as they've been watching the sport. Before fans considered the violence against women and against children, they grappled with the moral quandary of violence against fellow men and against the self. The verdict, submitted across the decades, has been a resounding shrug.

The fracas over Goodell's handling of the Rice-Palmer case was never an existential threat to the league, even if it did tar Goodell. His continued bungling of the process, as well as of the optics, pointed to deep veins of hubris and obliviousness that veered into incompetence. The whole mess should have cost him his job, especially in a year when hard discussions around rape, sexual consent, feminism, and violence against women came to the forefront of the American public square. Instead, we still have Goodell as commissioner and anti-violence public service announcements during NFL broadcasts that depict players struggling to talk about domestic violence. "Help us start the conversation," the tagline reads. Which is a bit odd, considering that all it took for Americans to start that talk in a big way was video of an NFL player punching a woman's lights out.

We had that talk, and then we went on watching football. Not for the first time, NFL fans this year tacitly accepted the league's crass venality as the price of watching Odell Beckham catch passes and Marshawn Lynch barrel through defenders. Conversation once again turned out to be cheap, and any meaningful boycott of the NFL seems remote. If a suit like Roger Goodell can weather the self-inflicted wounds of this year while predicting the league will nearly triple revenues to $25 billion by 2027, maybe you just have to sit back and watch, marveling.