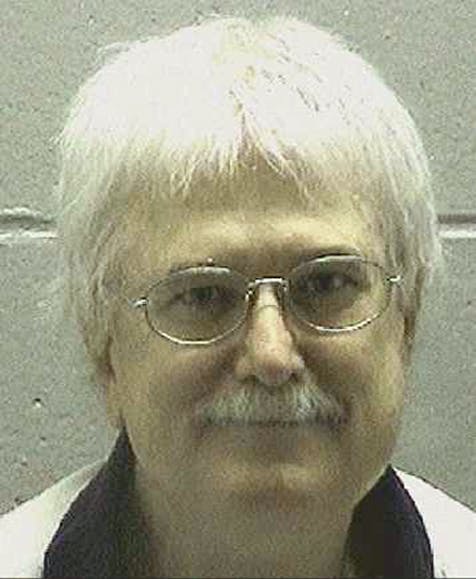

On Tuesday night, Georgia executed Vietnam War veteran Andrew Brannan for murdering Sheriff Deputy Kyle Dinkheller in January 1998. The dashboard camera in Dinkheller’s patrol vehicle captured their confrontation: Dinkheller pulled Brannan over for speeding, and Brannan’s reaction escalated rapidly from taunting Dinkheller to screaming at him, culminating in a firefight that left Dinkheller dead. The video, which has been uploaded to YouTube more than once, has been seen more than 1 million times. In addition to capturing the horror of Dinkheller’s final moments, the video shows how unhinged Brannan appeared. At one point, Brannan tells Dinkehller “shoot my ass,” then dances with his arms in the air, singing, “Here I am, here I am, here I am.” A moment later, Brannan advances on Dinkheller, screaming, “I am a goddamn Vietnam combat veteran,” before returning to his car to get his rifle. The Washington Post reported that the video has been shown to police in training “as an example of how quickly roadside stops can spin out of control.”

Brannan was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder in 1984 and, later, bipolar disorder. His defense team invoked his diagnoses in an attempt to avoid the death penalty. In 1986, the Supreme Court outlawed the execution of the mentally ill. In order to be executed, a person has to understand both what capital punishment means and why he is receiving it. A condition like chronic schizophrenia, where a person might experience frequent dissociation, could disqualify him. With a diagnosis like PTSD, where symptoms can include flashbacks, self-destructive behavior, and aggression, the ruling's application is less clear. A person could hypothetically commit a crime during a flashback or experience a violent rage because of his condition, and temporarily lose touch with reality. But it's extremely difficult to establish that a person's PTSD is relevant to his crime, and that it should be relevant to his sentencing.

Brannan’s execution was the country’s first in 2015. It happened despite how far our country has come in terms of recognizing PTSD as a debilitating disorder; despite Brannan’s known bouts of mental illness that, as the Post reported, landed him in the hospital “repeatedly” before he killed Dinkheller; and despite the fault that lies, at least somewhat, with a system that enables a person, even after being diagnosed with serious mental illness, to still possess a firearm. But Brannan isn’t the first veteran diagnosed with PTSD to be executed, and it seems unlikely he’ll be the last. In 1999 and 2002, two Vietnam War veterans diagnosed with PTSD were executed in California and Missouri, respectively. Another sits on death row in North Carolina.

In 2010, the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law published an article called “Combat Veterans and the Death Penalty: A Forensic Neuropsychiatric Perspective.” It warned, “With our nation's present conflicts, a new generation of veterans are returning home, many of whom have substantial psychopathology and are encountering significant barriers in accessing care.” The paper calls for a “legislatively or judicially enacted, narrow, categorical exclusion [from the death penalty] for combat veterans who were affected by PTSD or TBI [traumatic brain injury] at the time of their capital offenses.” Unfortunately, determining if a veteran has PTSD and if his condition influenced his behavior in a particular moment is not as straightforward as this recommendation.

The article acknowledges this. It describes the physical differences found in the brains of veterans with PTSD, as opposed to healthy civilians and veterans without PTSD, concluding that “PTSD and TBI appear to cause neurobiological dysfunction that threatens the capacity to inhibit violent behavior.” But, the article continues, “there is no medical or scientific literature of a study that has effectively tested this hypothesis.” (As I’ve written, we also don’t have evidence that repeated concussions affect violent behavior.) In the end, all we have are stories of veterans harming or killing loved ones, themselves, acquaintances, or even strangers, and the alarming statistical probabilities of these stories.

Also working against a vet’s case are the nuances of PTSD, once it is diagnosed. As Arizona State University Professor Betsy Grey writes in “Neuroscience, PTSD, and Sentencing Mitigation” for the Cardozo Law Review, “More problematic is assessing the validity of a PTSD diagnosis in a particular context.” Grey writes:

Most of the evidence for the diagnosis comes from interviews with the defendant, which leads to concerns about the trustworthiness of a particular diagnosis. Put simply, there are concerns that an individual who raises a claim of PTSD after committing a crime might be faking symptoms in order to avoid criminal punishment. But even if concerns about malingering in particular cases and the validity of PTSD as a legitimate diagnosis can be overcome, it is difficult to establish a causal connection between the disorder and the alleged criminal act because a defendant’s claim that he suffered a PTSD dissociative flashback while committing a crime can only be demonstrated by the defendant’s own testimony. Further, some studies have suggested a potential for “confirmatory” bias when a clinician is aware of an individual’s exposure to a stressor. In other words, if, for example, an expert knows that a particular defendant served in combat while in the military, the expert is more likely to find symptoms and diagnose that defendant with PTSD.

If our understanding of how PTSD affects veterans does not catch up to the rate at which we are producing veterans with PTSD (particularly from our ongoing engagements in the Middle East), we’re only likely to put more veterans clearly struggling with mental illness on death row. A diagnosis of PTSD should have guaranteed Brannan adequate mental health services, instigated precautionary measures to keep his community safe while he underwent treatment (like removing his firearm after his diagnosis), and affected his sentencing in the event of a crime committed during his illness. In fact, until we know more about PTSD and violent behavior, governors might consider staying all executions of veterans with the diagnosis, regardless of when they received it. We should worry about carrying out executions as scheduled only after we have executed certain PTSD treatment, safety, and research goals.