President Barack Obama’s landmark climate change deal with China last November raised hopes that India—the world’s third-largest greenhouse gas polluter—might commit to a similar deal. At the time, the Wall Street Journal asked, “Could India be next to set targets [for pollution]?” The answer to that question became a clear “no” after Obama arrived in India this week.

Instead, the U.S. and India issued a modest joint statement that set equally modest goals on clean energy and climate change. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Obama "made a personal commitment to work together to pursue a strong global climate agreement in Paris," Obama said. We won't know if this is true until the Paris talks, which are set for the end of the year. Otherwise, Obama and Modi’s announcements related mostly to clean energy, with the exception of a "breakthrough" on nuclear energy. India reaffirmed its commitment to phase out hydrofluorocarbons—used in coolants and aeresols—and is seeking private investments to meet a domestic goal of producing 100,000 MW of solar power by 2022, which is 33 times more than its current rate of production. By announcing a flurry of new clean energy and finance task forces and initiatives, Obama and Modi say they are working to reduce the trade barriers between the nations.

It’s notable that, unlike China, India has made no promises to cut its emissions, and Indian officials say they won't back away from coal. The country is also unlikely to make that promise when it submits a domestic climate plan to the United Nations by June, ahead of the Paris summit.

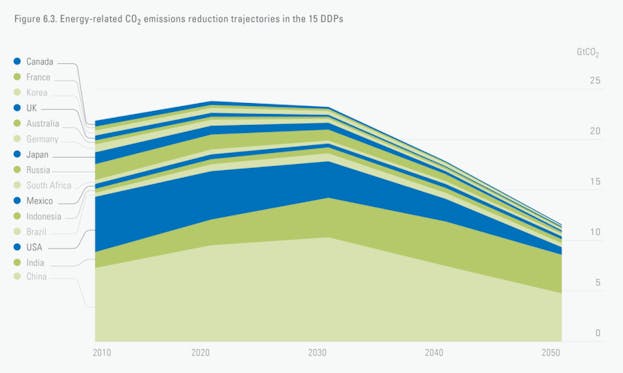

While China's deal was considered a breakthrough, India's reluctance to commit to cutting its emissions doesn't sink current expectations. India is "less important than China at this stage in the global climate change context,” said Robert Stavins, Harvard University's director of environmental economics. Per capita, India is still far below other major polluters, including China and the U.S. At some point emissions will need to come down, though that probably won't happen for another few decades. (According to one model, if deep cuts are made worldwide, India's emissions could conceivably continue to rise until 2040.)

That's not a surprise. Modi's challenges include how to bring power to India’s 300 million without it—a number equivalent to the entire population of the U.S. India also has issues similar to China's, specifically as regards terrible air pollution: New Delhi suffers from more days of dangerous air than Beijing. Ensuring India doesn't become too reliant on imported fossil fuels is yet another concern.

So, the strategy must be different for India. Obama can't simply reapply lessons from the China deal; the question here is how global climate interests can align with India's domestic concerns. "You have to work with each country on its own terms and what works with them," Peter Ogden, senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and a former Obama administration climate aide, said. “What’s smart is the administration found out and figured out how to work with China by integrating its local air pollution concerns [with] its global concerns.”

Let’s hope that India finds a way to rapidly develop without burning through fossil fuel reserves. Obama can work with India to make this possible.