Americans should worry less about cholesterol and more about sustainability in their diets, according to new recommendations from the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, America’s national dietary advisory panel. Every five years, the panel of scientists makes recommendations to the Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services, which the government generally adopts as policy—their advice formed the basis of the food pyramid, years ago. For the first time, these scientists are urging Americans to consider the environmental footprint of their food.

The panel recommends eating less red and processed meats, citing global food production as the leading cause of deforestation, biodiversity loss, and fresh water consumption. Livestock, specifically cow belches, contribute significantly to America’s methane emissions—methane being a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. Over the course of a year, one dairy cow produces as much greenhouse gas as a mid-sized car.

“Current evidence shows that the average U.S. diet has a larger environmental impact in terms of increased greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use and energy use,” the panel’s report states. “This is because the current U.S. population intake of animal-based foods is higher and plant-based foods are lower.” The chapter also suggests "a dietary pattern that is higher in plant-based foods, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, and lower in animal-based foods,” going on to say that this revised diet “is more health promoting and is associated with lesser environmental impact than is the current average U.S. diet."

At the same time, Americans can reduce their food waste for a more sustainable diet. A 2012 report from the Natural Resources Defense Council found that 40 percent of food purchased in the U.S. ends up thrown out.

The new recommendations have already stoked conservative alarm: In January, a fellow at the Heritage Foundation said that scientific federal dietary recommendations are part of the administration's "anti-meat agenda." The meat industry, meanwhile, argues that the recommendations are based on bad science. "If our government believes Americans should factor sustainability into their choices, guidance should come from a panel of sustainability experts that understands the complexity of the issue," Chief Executive of the North American Meat Institute Barry Carpenter said. Meat industry representatives have used similar self-serving arguments in the past whenever scientists warn against red meat consumption.

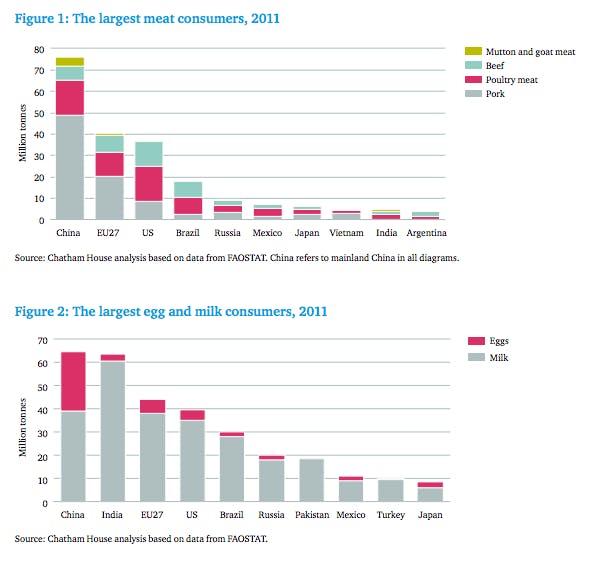

Other countries have already moved to incorporate sustainability into their nutrition policy, including Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Australia, and Brazil. The world has to feed a growing population in the next few decades that's consuming more and more meat—a report from the British think tank Chatham House notes that meat consumption will rise 76 percent by 2050, from 2007 levels; it will go up by 65 percent in the dairy industry. This is totally unsustainable. The Chatham House study estimates that nearly 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions already come from the livestock sector.

There are at least two avenues the government can take to make food production and consumption more sustainable: They can either recommend changes to individual behavior or regulate the agriculture industry directly. From the livestock sector's perspective, dietary guidelines are the lesser problem. Individual behavior changes very slowly, and won’t reduce methane emissions from the beef industry. To lower those industry emissions, a more ambitious regulatory approach is needed. The Obama Administration, however, has neglected studying methane emissions from agriculture, even as it is has released new (disappointingly weak) regulations on oil and gas methane leaks. As Slate's Eric Holthaus has pointed out, solutions exist. But the agriculture industry has successfully lobbied lawmakers against considering new practices.