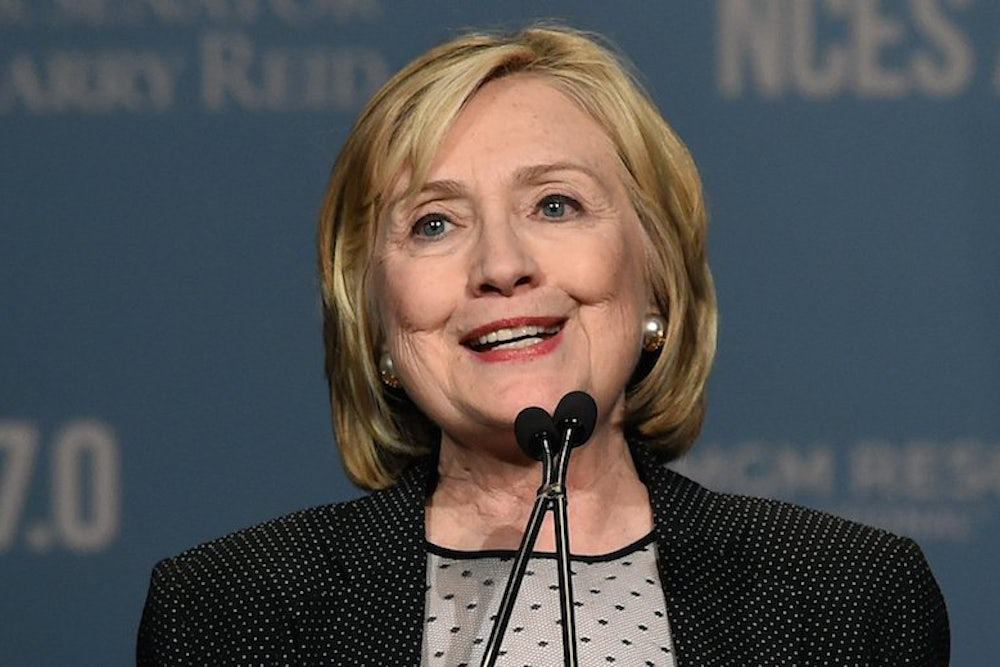

Conventional political wisdom often says climate change is a bottom-tier issue for voters. “It is very difficult to find an issue that voters place lower on the list than climate change,” GOP pollster Whit Ayres told the New York Times last fall. Ayres and other critics took Democratic donor Tom Steyer's failures in the midterm election as another example of where climate change wasn't as important to voters as the economy or national security. Hillary’s camp, on the other hand, has worked under the opposite assumption.

Campaign chairman John Podesta tweeted on Sunday that “tackling climate change & clean energy” would be a top priority of the presidential campaign, likely in an effort to placate environmental activists who aren’t so sure she will take their issue seriously.

Helping working families succeed, building small businesses, tackling climate change & clean energy. Top of the agenda. #Hillary2016

—

johnpodesta

To tackle the issue, Hillary’s best bet would be to incorporate climate messaging into every part of her platform. Including—and especially—her position on national security. In September, Clinton told the National Clean Energy Summit in Las Vegas that it is “the most consequential, urgent, sweeping collection of challenges we face.” This earned some derision from presidential candidate and Senator Rand Paul, who said, “I don’t think we really want a commander-in-chief who’s battling climate change instead of terrorism.” Except: The military knows that it is a threat. Clinton could draw on her diplomatic expertise as secretary of state to stress climate change as a global security problem.

Indeed, an independent report published this week from the members of the G7 named climate change the “ultimate threat multiplier: it will aggravate already fragile situations and may contribute to social upheaval and even violent conflict.” The paper stresses that already fragile states are the most vulnerable because climate change causes more competition for resources like water and land, leads to food price instability, displaces populations, and threatens coastal infrastructure.

The Pentagon has used similar language to describe the looming threat of sea level rise and extreme weather, also citing how it endangers coastal military bases and infrastructure. Another report, commissioned in 2012 by 20 governments, found 400,000 deaths worldwide each year attributable to climate change. They’re linked to heat waves, food insecurity, water safety, and mosquito-related diseases like malaria. Terrorism gets much more attention than any of these issues, but maybe it shouldn’t. Though 2013 was a peak year for deaths caused by terrorist attacks, these attacks were also collectively responsible for far fewer deaths, at 18,000. Terrorist attacks are usually limited to specific regions—and in 2013 mostly affected only five countries—while the impacts related to climate change are spread across the world.

Clinton could also make climate change about ensuring economic prosperity. Clean energy is a winning political point, as a technology that is, uh, cleaner than coal, and also as a technology that’s saving consumers and businesses money. She could borrow a line from President Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign: that clean energy is “American-made energy” to counter expected “war on coal” conservative attacks.

Even so, she should take this a few steps further. The Obama Administration has been laying the groundwork to discuss climate change as an economic threat. A White House report last year showed that taking no action on climate change would cost the U.S. economy about $150 billion a year, far greater than the cost of investing in renewable energy and moving the economy away from coal.

Clinton can build on this in her campaign, to sway swing states with robust real estate, tourism, and agriculture industries. The GOP will certainly argue that taking action costs too much to taxpayers, but Clinton has a strong case to argue that doing nothing is far more irresponsible.

The only candidate that acknowledges climate change is a reality has a special opportunity to highlight the advantages of climate action and the absurdity of the GOP candidates who say the science is wrong. She will sound like a candidate who wants to tackle present-day problems—the same issues the military and economists say should be priorities—while Republicans struggle to find a way to talk about the issue without sounding ridiculous.