You might say Anderson Cooper had the proper reaction when he was informed that one of his ancestors held slaves, and had in fact been killed by one of them with a farm hoe. After a “wow” and a “whoa,” the CNN anchor told host Henry Louis “Skip” Gates on a recent episode of the PBS genealogy show Finding Your Roots, “Oh, my God. That’s amazing. This is incredible. I am blown away!” When Gates asked whether the ancestor deserved it, Cooper immediately replied, “Yeah. I have no doubt… He had 12 slaves. I don’t feel bad for him.”

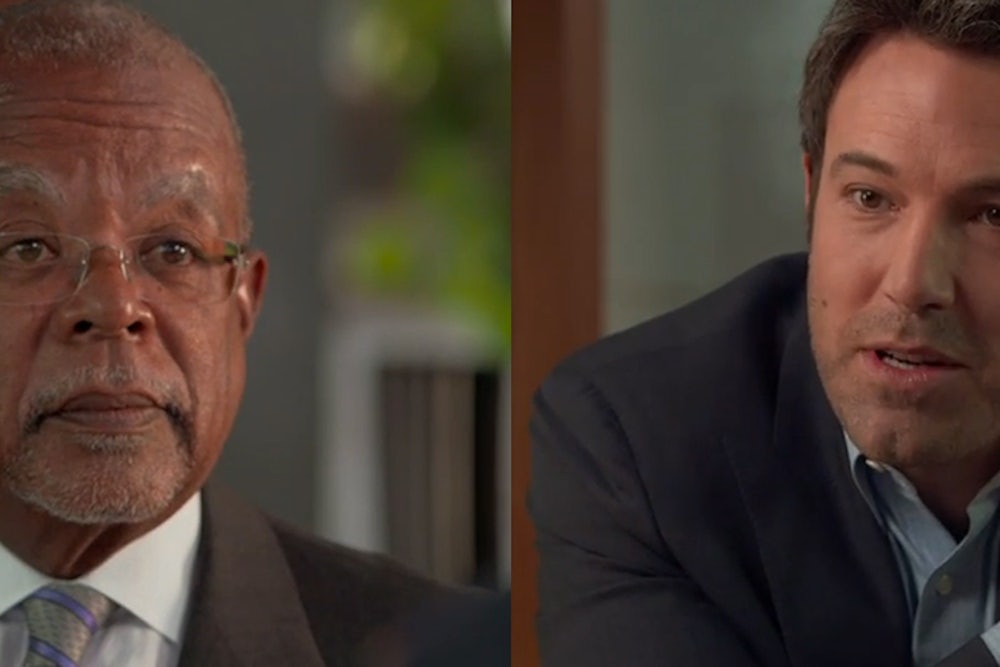

Perhaps it was the shock of seeing the actual name on the parchment that got to him, but I’m surprised Cooper was surprised. It isn’t terribly uncommon for white Americans, particularly those like Cooper with Southern roots, to have had slave-holding ancestors. This is something Ben Affleck might have considered before he agreed to be a guest on Gates’ program last October. As we learned last week from Sony Wikileaks, when Gates told Affleck he had slaver ancestors, the Oscar-winning director and actor reacted with embarassment, and then made a plea for special treatment. As one of the leaked Sony email exchanges posted by WikiLeaks revealed, Affleck asked Gates to remove any reference to that particularly ugly piece of family history from the episode. What kills me is that Gates not only allowed it—he helped Affleck do it.

The email making that request of Sony Pictures co-chairman and chief executive Michael Lynton didn’t come from Affleck or his representatives. It came directly from Gates, the Harvard professor and host. “Here’s my dilemma: confidentially, for the first time, one of our guests has asked us to edit out something about one of his ancestors—the fact that he owned slaves,” Gates wrote to Lynton on July 22 of last year, according to the leak. “Now, four or five of our guests this season descend from slave owners, including Ken Burns. We’ve never had anyone ever try to censor or edit what we found. He’s a megastar. What do we do?”

It is utterly unacceptable that Gates, one of the world’s foremost experts in the African diaspora, would capitulate to someone seeking to hide his family’s slaveholding past. Yes, it’s only a television show. That’s part of the problem.

Carol Anderson, an associate professor of African American Studies at Emory University, and the author of possibly the best op-ed on Ferguson I read last year, told me that while Gates is ultimately responsible for maintaining the scholarly integrity of a show that presents genealogy in an easily digestible fashion, we should not mistake Finding Your Roots for scholarship.

“Part of what happens is that we conflate what a PBS special is with academic work,” Anderson said. “We have to understand that so much of what we see there is packaged for a non-academic audience that wants the picture of really deep, intellectual discussion, but is not quite ready for what that means. I think this [incident] with Ben Affleck really highlights that. Being a celebrity has a lot to do with how you package and market yourself. You may not want to come to grips with being the descendant of a slave owner. It’s not the conflict with rigorous academia that is surfacing; it’s what happens when academia meets entertainment.”

Still, Affleck should have known better. He is hardly unfamiliar with the travails of African peoples; he is the founder of the Eastern Congo Initiative, an advocacy group that seeks to improve conditions and quality of life for people there. But as courageous as that work is, this move reeks of needless cowardice. If Affleck was worried that a slaveholding ancestor might sully his image or damage his credibility as an ally, why would he agree to let Gates venture into his past at all? Perhaps he never considered the possibility, but I have my doubts. And if the editors of US Magazine and People happened to catch his episode, how much would it matter if they posted a story about it?

Previously oblivious people are starting to take notice of the symptoms of the systemic racism that undergirds our nation’s foundation, chief among these income inequality and black death at the hands of the police—even if it’s because social media and heightened media attention are forcing them to take notice. But too many Americans are still thinking about racism, and specifically slavery, in an anecdotal fashion. This is happening because we take too many shortcuts with our history.

“Slavery is packaged as a society of individual bad people,” Anderson told me, adding that slavery generated a heavy percentage of the American gross domestic product before the Civil War. “Nobody’s ready to deal with that. Instead of seeing a system of oppression, it makes it more palatable.”

Anderson added that presentations of slavery in popular culture typically comport with the entertainment industry’s need to entertain. Think of two recent examples: Django Unchained and 12 Years a Slave, the second a powerful and wrenching film which, like Affleck’s Argo the previous year, won the Academy Award for Best Picture. I, too, got caught up in rooting for Chiwetel Ejiofor’s Solomon Northup and his fellow slaves not only to escape their unjust bondage, but to whoop Paul Dano’s overseer in the process. Django, Quentin Tarantino’s live-action slavery cartoon, was a hoot to watch. You certainly see the Bad Guy Slaveholders and House Negroes all get it in the end. But no matter how each film indulges the caricatured horror of slavery and presents stock characters such as the Good White Guy (Brad Pitt in 12 Years, Christoph Waltz in Django), they’re still two stories. What happens after we digest them? Too often, the same thing that happens to anything else we consume.

Gates’ show, when it does reveal that its white guests descend from slaveholders, provides the same empty intellectual calories. Even when he isn’t capitulating to stars’ whims, Gates encourages anyone consuming his product on PBS to deal with the problem of slavery in a disposable fashion, one that ignores the systemic legacy of that torturous bondage. I hope he doesn’t just start texting Sony executives instead of emailing. If his goal is to do a show that’s the scholarly equivalent of 23andme, he has been successful in that endeavor. But we should expect more of an academic of his caliber.