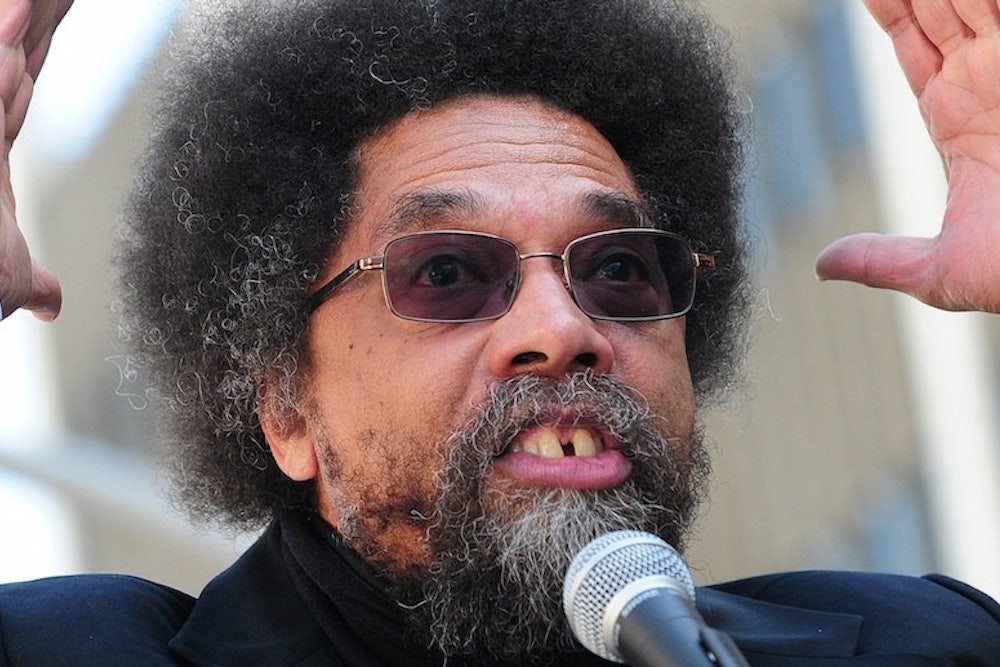

There has been a great deal of commentary about my article on Cornel West published in The New Republic’s May issue. I’d like to take a few lines to address the most salient responses, though hardly at the length of my original essay.

Complaints of length aside,1 many wondered why I published my essay now. After all, West has been extremely hostile and unapologetically vicious for quite a while. Did I time my article, as some suggested, as a bid for Hillary Clinton’s attention, and to show the Democratic establishment that I could make mincemeat of one of their most vocal critics? I have often accused the Democrats of lacking spine, so that makes little sense. There’s a far simpler and unsexy answer: I published it when I finished it. I’m working on a book on President Obama and race and that has taken the bulk of my writing time. Between teaching classes, offering lectures, preaching in churches, and, yes, protesting the death of black folk and speaking at marches against police brutality, it took me nearly a year to compose this essay. When I got it into good shape, I offered it to The New Republic.

Why this magazine, many have asked, even those who tended to agree with my vigorous criticism? The New Republic has had a horrible reputation for publishing racist work that insults and stereotypes black life. My worries about racist legacies haven’t kept me from teaching at major American universities either, so I usually stay and fight the good fight. Why not publish in, say, Ebony or Essence magazines, two venerable black publishing institutions? My essay is not quite in their wheelhouse; neither magazine, where I’ve published quite frequently, is geared to the philosophical meditation on prophetic vocation, scholarly craft and writerly art—or the sharp polemics—that I offer in my essay. I can’t remember the last essay at the length I wrote appearing in either publication. As for The New Republic’s checkered racial past, no one made that argument more forcefully than, well, The New Republic. It performed its own racial autopsy and did what I’d like to see more white institutions, brands, and entities do: own up to their racist past, navigate past guilty racial catharsis, and broaden their intellectual horizons by seriously engaging the ideas and identities of black folk and other people of color. The reborn New Republic is pushing forth with its history at its back and the digital future looming before it, all while preserving its pedigree as a place for serious thought. I welcome the opportunity to offer my reflections between its covers.

But it is the fact that I published my thoughts about the tragic missteps of a brilliant black thinker at all that has a lot of folks upset. Why not simply call up West and resolve our differences? West and I have talked on occasion, though admittedly not in a long time given his bitter denunciations of me and others in the media spotlight. But our differences aren’t merely personal; West’s diatribes and unprincipled attacks hamper the quest for truth and damage the debate—even if one agrees with the substance of his arguments. One might ask, why not sign off on West’s views even if they happen to be harsh and vicious when there is agreement about some of his claims? Because in black culture, and surely beyond, how one says what one says communicates moral intent beyond the words spoken. The means to justice are just as important as the ends pursued. If, for instance, I can’t see, and insist, on Obama’s humanity, as I criticize his actions, then I undermine every claim I make under the banner of #BlackLivesMatter. If all black lives don’t matter, then no black lives matter. West himself said that we “must have an unconditional commitment to try to keep track of the humanity of each and every person to give us the courage to love, serve, and sacrifice.” Using hateful language to describe or decry former comrades is a failure to observe West’s own principle. These issues cannot be resolved in private; they are stubbornly public matters that demand public debate on page or stage. Interestingly, many of the same folks who are upset about my public grappling with West’s behavior are or have been silent about the nasty things he said and did in public to touch things off. Regarding the administering of discipline to children in public, the old folk in the black communities I lived in say: “Where you did it is where you get it.” I’m not advocating corporal punishment or suggesting I want to spank West. What I am saying is that West’s verbal brutalities, and the glaring contradictions that suffocated his moral and intellectual authority as he hurled invective at other public figures, cried out for a public response. I offered the best and most comprehensive response I could give.

Many have wondered if my essay was a hit job on West. Hardly. West's defenders (and even West himself) are doing him a disservice by saying this is just about personalities. West’s past work merits the honor of treating him as an important thinker—which he is. And if West is a major thinker, then devoting 10,000 words to a sustained and informed critique isn't a waste of time—it's the type of careful, critical engagement that someone of West's stature merits and needs. Neither is this about protecting the president from rigorous criticism. I’ve been consistently critical of Obama. Just a few months after his first inauguration in 2009, I said to radio host Davey D—in words that left-wing Black Agenda Report, my perennial critic, labeled as “scathing words of criticism”—that we “are so grateful for having a black person in the office we don’t demand anything of him,” and that “I expect the president of the United States to address issues of race.” I argued that Obama has “fallen short and we must hold him accountable.” In 2010, on MSNBC, the network that West claims is besieged by “the rent-a-Negro phenomenon,” I argued, “I think that we should push the president. This president runs from race like a black man runs from a cop.”

And last year on "Face the Nation," I argued that Obama should be far more vocal about the fires of unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, in the wake of the police killing of unarmed black youth Michael Brown. “This president knows better than most what happens in poor communities that have been antagonized, historically, by the hostile relationship between black people and the police department.” I said that it “is not enough for him to come on national television and pretend that there’s a false equivalency between police people who are armed, and black people who are vulnerable. … He needs to use his bully pulpit to step up and articulate this as a vision.”

Following my remarks on television, I penned an op-ed in the Washington Post critiquing Obama’s remarks on Ferguson as “tone deaf” and wrote that he “is a gifted leader whose palpable discomfort with discussing race has made him a sometimes unreliable and distant narrator of black life.” These comments riled the White House and cause a heated public exchange with a senior presidential adviser.

One thing, however, is true: I refuse to fling epithets at Obama as I seek to push him in the right direction. When West recently complained of “character assassination” in a brief Facebook posting, he surely forgot the way he’s aimed his harmful words at the character of folk he used to deem friends and comrades. If calling folk liars, prostitutes, traitors, plantation Negroes, and bootlickers isn’t character assassination, it’s hard to tell what is.

West again cloaked himself in opposition to “allegiance to the status quo” with which he often has no problem at all aligning himself. A few years ago, for instance, West bragged of “kicking it at Jay Z’s townhouse with the man himself” and advising American Express, at their request, if they should offer the rap star a commercial. West the democratic socialist proves his courage and risk taking by playing adviser to a storied American corporation to vet a legendary multimillion entertainer who he recently blasted as “an example of folk who get so elevated that they don’t show courage and take a risk for something that is bigger than them.”

West readily embraced the racial status quo when he defended Bill Cosby’s heartless assaults on the black poor in his infamous “pound cake” speech and his subsequent “blame the poor tours” conducted in black America. When the creator of “Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids” assailed the black English of young folk and implored them to speak “correct” English, West was there to pat him on the back. “Bill Cosby’s gallant attempt to correct the attitudes and actions of young people is significant,” West argued. “Young people must become more multilingual.” Never mind the valiant attempts of Oakland, California educators to implement Black English to foster the literacy of black youth. And never mind Cosby’s harsh attacks on young blacks as “dirty laundry,” and his cruel indifference to poverty, crime, deteriorating schools, stagnating wages, dramatic shifts in the economy, downsizing of jobs, chronic unemployment and capital flight, factors I underscored in my book Is Bill Cosby Right? Or Has the Black Middle Class Lost Its Mind? West found in Cosby a fellow traveler eager to indict black behavior as the crux of black suffering. West said that Cosby “is speaking out of great compassion and trying to get folk to get on the right track, ‘cause we’ve got some brothers and sisters who are not doing the right things. … He is trying to speak honestly and freely and lovingly, and I think that’s a very positive thing.” So positive that West believed that Cosby had earned the right to demean poor blacks because of his philanthropy to black colleges. One gets the feeling that philanthocrats who foster social change and shape political agendas through their wealth don’t bug West as much as oligarchs or plutocrats. It is clear that West often shifts views and judgments and inconsistently adheres to principles he dogmatically urges on others.

It makes perfect sense for a black leftist to challenge Obama’s rightward drift into what West termed “a Wall Street presidency, a drone presidency, a national security presidency” where crooked executives and torturers go unpunished. Some took me to task for not explicating the array of West’s political activities. However, my essay wasn’t a political profile but a piece of writing rooted in research and reflection with a strong point of view. I leave the breadth and depth of West’s political activities to his advocates or biographers. My interests were far more specific: probing the vituperation that clouds West’s political stances no matter their variety or virtue. I aimed to challenge the wisdom and decency—two concepts that mean a great deal to West—of conducting campaigns of vitriol in the name of social prophecy.

The white left is mad at Obama too, but neither Michael Moore nor Roger Hodge resorts to the epithets that mar West’s analysis. And it isn’t as if West cannot be civil and gracious when disagreeing with a colleague—at least not his white ones. When Obama was first elected, West said he was under the “impression that [Obama] might bring in the voices of brother Joseph Stiglitz and brother Paul Krugman” to get the country on good economic footing. But “brother” Krugman wrote last year a rousing defense of Obama, admitting that, unlike other liberals in 2008 who were “wildly enthusiastic” about the candidate, he was “skeptical.” Now he argues that Obama “faces trash talk left, right and center—literally—and doesn’t deserve it” and “has emerged as one of the most consequential and, yes, successful presidents in American history.” West claimed Krugman is “wrong” because he’s “a dyed-in-the-wool, genuine, progressive liberal. He’s not a leftist.” West simply throws down the “lefter-than-thou” card and offers gentle rebuke to his friend instead of vicious ad hominem attacks. West is far more feral with his erstwhile black comrades: After Obama confronted West at the 2010 convention of the National Urban League, West said later that “I wanted to slap him on the side of his head.” The history of black bodies being unjustly assaulted makes such violent fantasies troubling, even more so in light of the epidemic of unarmed black folk dying at the hands of the police.

That epidemic has made some question the release of my essay as the plague of black death spreads. It’s good to remember there’s rarely a convenient or ideal time to engage messy, complicated issues, although it’s hardly impossible to address more than one issue at a time. On the Friday before my essay on West published, I published an op-ed for the New York Times on the killing of Walter Scott in South Carolina by North Charleston police officer Michael Slager, arguing that the lived experience of race for blacks often feels like terror, whether it’s the fast terror of police killings or the slow terror of unmerited school expulsions. Some have suggested that we should only deal with police brutality and the killing of black folk. But most of us are used to grappling at the same time with competing, or even parallel, interests, and there’s little fear that critical attention will be diverted from the most pressing matters at hand. The healthy and humane treatment of human beings, although far more pressing in the case of the police and black masses, links the argument I made about respecting one’s opponents to the movement for the recognition of the value of black life.

It was curious to read and hear the concern that my essay was racially divisive, that black folk should come together under the banner of racial unity—something West himself warned against long ago as one of the “pitfalls of racial reasoning.” The hunger for unity can’t submerge the real differences that separate us nor silence the demand for just treatment in the group. Those who stood by while West savaged the reputations of many good folk in the name of righteous indignation have fomented unnecessary division and have reaped the harvest of unmitigated viciousness. It tells on us morally as a people that there was no preemptive hue and cry against the tongue-lashings West routinely delivered before the publication of my essay. Why was there no concerted effort to pull West aside in love and warn him against the detriment of fulminating against his opponents with little regard for the toll it might impose, or for the bad example it might set? (Although one needn’t worry, as some have stated, that it would be horrible for aspiring black scholars and others to witness the call to account of someone who may have gone off the rails.) The conditions that made my essay necessary might just as easily have been removed by taking West to task for his bad behavior.

One thing should be clear, however: We must show each other the kind of love and regard we are hungry for, even if that love is tough, though it can never be unjust or destructive. I join Cornel West in the call to focus on the issues that truly matter—including police murders, poverty and mass incarceration—but starting with how we struggle together to achieve a just and equal society by treating each other the same way we want the broader society to treat us. Anything less mocks the belief that all black lives matter.

Alas, twitteracy—or literacy in the age of Twitter, Facebook and other social media—has severely shrunken our attention spans. When I was a tyke, a 10,000-word essay hardly appeared forbidding, though it seemed to trouble a number of contemporary readers that they’d have to slog through more than 140 characters.