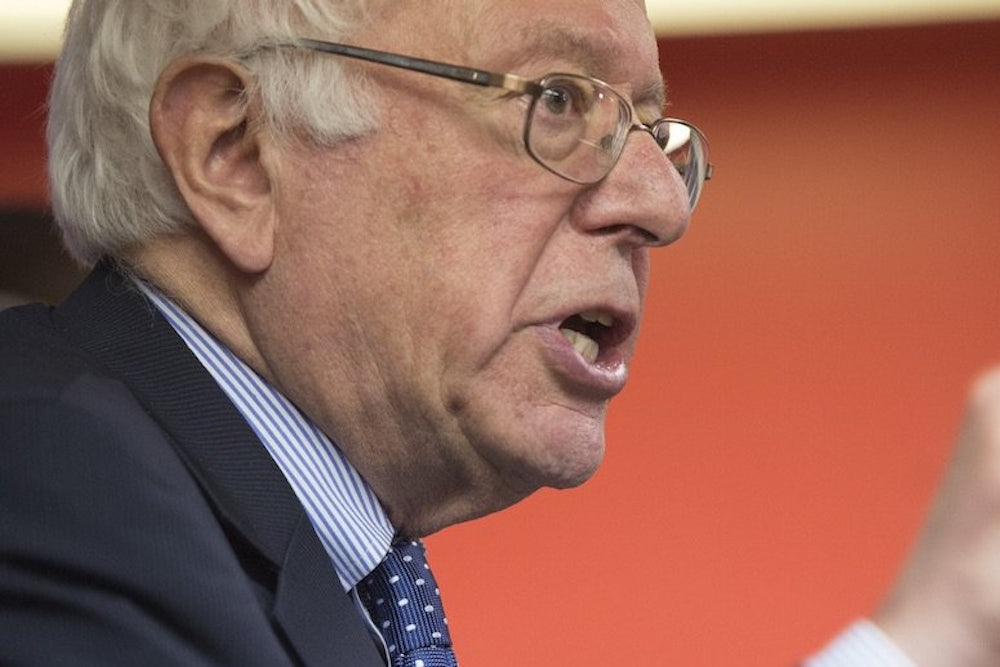

Earlier this week, Vermont senator and presidential candidate Bernie Sanders released his Family Values Agenda, a package of policy proposals aimed at expanding employees’ rights to paid time off. The agenda, which includes paid leave for sickness, vacations, and newborns, is the only program of its type announced so far by any candidate in the nascent presidential contest. If implemented, it would represent a significant leap forward for the United States—but only take us halfway to where we need to be.

Sanders’ family benefits package has three parts to it, only one of which is, strictly speaking, new. The first part is an endorsement of Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s FAMILY Act, which levies a small payroll tax to fund twelve weeks of publicly financed, job-protected paid leave for parents of newborns. Under the FAMILY Act, parents would receive welfare payments equal to 66 percent of their prior pay to allow them to support themselves while caring for and bonding with their babies. Sanders has long supported the FAMILY Act.

The second part is an endorsement of Senator Patty Murray’s Healthy Families Act, which mandates that employers provide earned sick leave for their employees. Under the existing legislation, employers would be required to provide a minimum of one hour of earned sick leave for every 30 hours worked, up to seven days of paid sick leave per year. In effect, the bill mandates that employers provide around 3 percent of employee compensation in the form of sick leave. Sanders has long supported the FAMILY Act, too.

The final part, and the only new part, is the Guaranteed Paid Vacation Act, which would mandate that employers provide 10 days of paid vacation for all employees that have worked under the employer for at least a year. This mandate would significantly increase minimum vacation leave from the current level—zero days—but it would still lag many other countries like France (30 days) and the Nordic countries (25 days).

While paid leave from work is an integral part of healthy family life, much more must be done to support the needs of working families. Specifically, a robust family benefit regime should include the smoothing over of child-rearing costs, which are enormously high and hit families the hardest early in their careers when they are least able to afford them. In practice, this means extending child-care benefits to all parents of children below school age and providing families with a monthly per-child cash benefit.

One of the fundamental problems of modern capitalist economies is that they provide families the least amount of market income when they are at peak fertility. The average woman gives birth to her first child at age 26, which is just one year into what economists refer to as the prime working years (ages 25-54). This means that families of young children are at the bottom of the career ladder right at the time as they are saddled with $10,000 or more in annual child-related costs. In some states, day care alone can cost that much.

For a huge portion of the young parent population, these costs are simply unaffordable. According to my own calculations of the American Community Survey, 40 percent of children between the ages of zero and two have family incomes below $40,000 per year, and 20 percent have family incomes below $20,000 per year. These family incomes grow 30 to 60 percent by the time the child reaches 17, but that does nothing to help a family afford the sky-high costs of childcare and other child-related expenses when they are still young and relatively poor.

Just as we don’t expect families of children between the ages of five and 17 to be able to shell out the $12,500 per kid that it takes to care for and educate a child from kindergarten through the twelfth grade, we shouldn’t expect families of children between the ages of zero and four to be able to shell out a similar sum of money for daycare. Public child care benefits, whether provided through subsidized day care centers, directly to families, or through some hybrid of the two, are the only way to correct this income distribution problem.

While child care benefits would help to alleviate some of the most significant financial burdens of parenthood, it would not eliminate all of them. When families have children, they have increased housing costs, food costs, transportation costs, not to mention diapers and clothing and all the rest of it. As with day care costs, these hit families when markets distribute them the least amount of income. A society committed to supporting families in the face of the market’s broad disregard for the needs of children and parents should supplement market income with per-child transfer income. Specifically, a $300 per child per month benefit paid out by the Social Security Administration would go a long way to smoothing over the unique financial problems families with children face.

Ultimately, supporting families requires putting up actual money. The share of the national income we distribute to families with children, especially families with young children, must go up. Sanders’ proposals to give parents more time off of work to spend with their children is important, but actually being able to comfortably afford children is perhaps more important still.