Modern-day racists rarely admit to being racist. They don’t discriminate, they claim—and if they do, well then, they really didn’t mean it, so it doesn't count. But the Supreme Court provided a sharp reminder on Thursday that structural racism doesn't need to be on purpose. In a 5-4 ruling, the Court upheld the ability to bring forward claims of discrimination under the 1968 Fair Housing Act when housing practices have a “disproportionately adverse effect on minorities,” regardless of intent behind them.

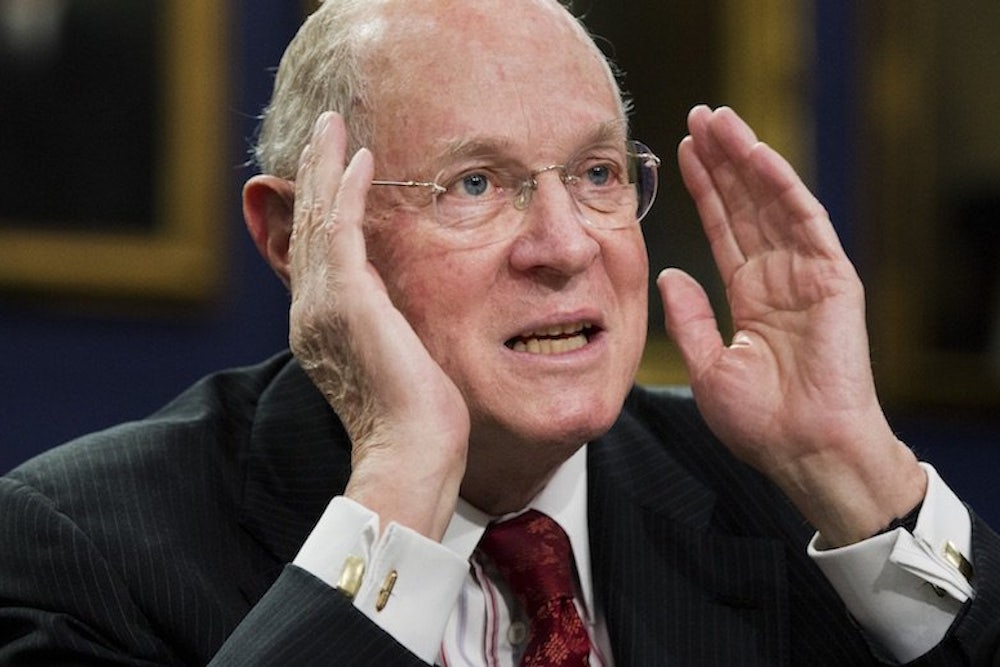

In the case, Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs. vs. Inclusive Communities Project, a community non-profit that alleged that the Texas housing authorities had exacerbated segregation by providing too many tax-credits for developers to build low-income housing in the black inner-city and too few to build them in whiter, suburban neighborhoods. As Justice Anthony Kennedy explained in the Court's majority opinion, it didn’t matter whether the policies were intentionally racist. The challenge to those housing policies rested on the claim that they had a “ ‘disproportionately adverse effect on minorities’ and are otherwise unjustified by a legitimate rationale.”

The Court preserved the ability to file such “disparate impact” claims under the Fair Housing Act, preserving a key pillar of civil rights law. The Court isn’t arguing that all policies that have a disparate impact are illegal. Rather, it is affirming the ability to challenge those policies that create “artificial, arbitrary, and unnecessary barriers” and that don’t serve a larger “valid interest.”

“This decision retains the essential protections of the Fair Housing Act, meaning the law will continue to serve as an important tool in rooting out pernicious forms of racial segregation and discrimination,” said Dennis Parker, director of the ACLU's Racial Justice Program, in a statement.

Kennedy’s opinion is also a lesson in what structural racism is, how it’s changed, and why it matters. It doesn’t need hateful speech or symbols to thrive; instead, structural racism has managed to persist because it remains embedded in the foundation of larger institutions, conventions, and practices, and over time, its more explicitly racist history and origins have been largely subsumed. As Kennedy explains, “De jure residential segregation by race was declared unconstitutional almost a century ago, Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917), but its vestiges remain today, intertwined with the country’s economic and social life.” He goes onto explain how cases of modern-day housing segregation “can be traced to conditions that arose in the mid 20th century,” including redlining and racist housing covenants.

Modern-day forms of discrimination are often less explicitly racist, and it’s partly because they don’t need to be. Decades of housing segregation have helped create deep pockets of urban poverty and other economic disparities, providing additional proxies for racial discrimination. As Kennedy points out, “if a real-estate appraiser took into account a neighborhood’s schools, one could not say the appraiser acted because of race.”

But Kennedy concludes that doesn’t mean that housing practices should escape legal scrutiny if they have needlessly discriminatory outcomes. Good schools in fact, were among the criteria that Texas used to decide where to offer tax credits for low-income housing developments—and criteria that helped keep them out of whiter, more affluent suburban areas, according to TCP’s challenge. Kennedy argues that such legal challenges can also help reveal deeper, more covert forms of discrimination embedded in institutions, policies, and practices—the kind of structural racism that is not obviously discriminatory on its face:

Recognition of disparate impact liability under the FHA also plays a role in uncovering discriminatory intent: It permits plaintiffs to counteract unconscious prejudices and disguised animus that escape easy classification as disparate treatment. In this way disparate-impact liability may prevent segregated housing patterns that might otherwise result from covert and illicit stereotyping.

Kennedy believes that such claims are particularly important because of racial segregation continues to persist and divide our society, even though explicit, Jim Crow-style racism has become less legally and socially permissible. “Much progress remains to be made in our Nation’s continuing struggle against racial isolation,” he writes, pointing to discriminatory zoning ordinances and other housing practices that disparate impact claims have challenged. There are major implications for the financial industry as well: In the run-up to the housing crisis, black and Hispanic borrowers were disproportionately targeted by lenders for high-risk, subprime mortgages, and disparate impact claims forced banks to make record settlements with these victims.

Kennedy’s opinion reflects an expansive understanding of discrimination that recognizes how policies can perpetuate and exacerbate racism, whether or not the people behind them intended to be racist. It also pushes back against the Court's recent efforts to cast racial discrimination as a thing of the past. In the Court's 2013 decision knocking down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act—which Kennedy joined—Chief Justice John Roberts wrote “things have changed dramatically” since the 1960s in terms of barriers to voting. Roberts joined the dissent in the Fair Housing case, and the Court's conservative justices again tried to define racism down.

In his dissent, Justice Samuel Alito argued that the FHA only intended to outlaw intentional racism, comparing the statute to hate crimes. “Hate crimes require bad intent—indeed, that is the whole point of these laws,” Alito said. In another dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas went even farther, insisting that many racial disparities are inevitable—sometimes even desirable—facet of human nature. “The absence of racial disparities in multi-ethnic societies has been the exception, not the rule,” Thomas wrote. He argued, moreover, that “racial imbalances do not always disfavor minorities,” citing the success of Jews in Poland and the dominance of black NBA players, among others. (Given the ultimate fate of Polish Jews during World War II, it was perhaps not the most apt example.)

According to Thomas, when there are negative outcomes associated with racial disparities, we should not be so quick to blame institutions for producing them. “[D]isparate-impact proponents doggedly assume that a given racial disparity at an institution is a product of that institution rather than a reflection of disparities that exist outside of it,” he wrote. This is Thomas essentially giving a free pass to institutions that may needlessly perpetuate discrimination, and whose actions are shaped by human hands rather than nameless outside forces.

Citing structural racism shouldn’t be as a cop-out to blame “the system” wholesale; instead, it’s a way to understand how institutional policies and practices that can needlessly exacerbate long-standing racial disparities. Kennedy is clear that the government and businesses shouldn’t resort to the opposite either, warning that using “numerical quotas” or other race-based criteria for creating more equitable housing could be unconstitutional.

He invoked President Lyndon Johnson’s Kerner Commission, which was set up to investigate the forces behind the 1967 race riots. The Kerner Report, Kennedy explained, found “both open and covert racial discrimination” was fueling economic inequality and housing segregation. The FHA was passed just weeks after its findings were released, and Kennedy concluded that we face the very same task today: “The FHA must play an important part in avoiding the Kerner Commission’s grim prophecy that ‘[o]ur Nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.’”

It is clear, from last week's murders in Charleston and subsequent debate over the Confederate flag and “Southern heritage,” that we have not yet moved beyond our ugly history of racial bias, segregation, and discrimination. Kennedy realized this truth applied also to the FHA, and that whether someone has the best intentions has little to do with it.