The Supreme Court’s decision in King v. Burwell last week preserved the Affordable Care Act's subsidies for all enrollees, and Chief Justice John Roberts’s vehement dismissal of the plaintiffs’ arguments signals that the Court is averse to further efforts to repeal Obamacare through litigation. The contest over health care reform therefore shifts from the courts back to politics: The ACA likely will be an issue in the 2016 election. But what should be done to improve it?

The ACA has only partially achieved its goals. Its principal goal was to get coverage for uninsured Americans, because the U.S. was facing a crisis: Not only were many Americans uninsured, but also their ranks were steadily growing:

That trend reversed sharply after the ACA passed in 2010. Nevertheless, at least 10 percent of Americans still lack health insurance. It will be difficult to reduce that percentage significantly, as the Supreme Court’s 2012 National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius decision allowed each state to make its own choice about whether to expand the Medicaid insurance program to make more poor families eligible. Many red states refused the expansion, even though those very states have especially high concentrations of impoverished, uninsured families. Unless those states change their policies, universal coverage will remain elusive.

So, the first piece of the health care reform agenda is clear: Reformers must convince voters, legislators, and governors in those states to expand Medicaid.

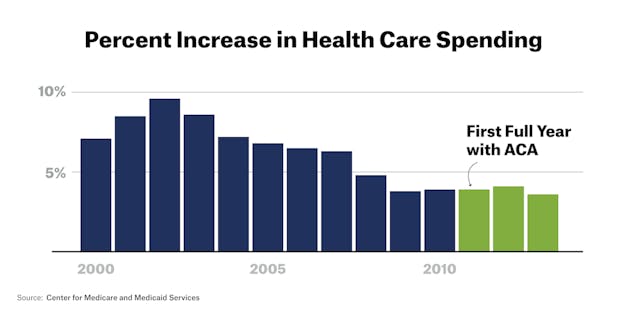

The ACA was also designed, in lesser part, to address the growth in health care spending. The U.S. spends far more per person on health care than any other country, while achieving only mediocre results in population health. Again, the problem was getting worse: Our annual increases in health care spending are greater than overall inflation. Unchecked growth in health care spending threatens the fiscal solvency of Medicare, and with it every other governmental function that progressives value.

The good news is that the growth in U.S. health care expenditures has dropped from 9.6 percent in 2002 to 3.6 percent in 2013. But the decline in the annual increase in health expenditures seems to have stalled since 2009; at a 3.6 percent growth rate, health expenditures will have doubled again by 2035.

Thus, the second piece of the health reform agenda is to reduce the growth in health care cost while improving the quality of care. But while you can reform health care insurance with a law, changing the cost and quality of care are both too big and complicated to be reformed through legislation.

Given that, what can we achieve through politics? First, we should continue Medicare's payment reform experiments, which are part of the ACA, and apply what works to the rest of the health-care system. The key idea in these experiments is the Accountable Care Organization (ACO). Whereas traditional payment systems reward doctors for doing more, whether it’s good for the patient or not, ACO doctors receive higher payments if they reduce growth in health expenditures for their patients while maintaining or improving outcomes and patient experience. Preliminary research indicates that ACOs are holding down the growth in cost without compromising patients’ health.

Research is also critical: Health care reform has to be driven by results, not political beliefs. Programs should be selected based on evidence, such as the results of randomized clinical trials. Every new reform should collect rigorous data to determine whether it works.

This data-driven approach to change won’t happen unless we strengthen the institutions that fund biomedical science, including the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Health Research and Quality, a division of the Department of Health and Human Services that's the principal funder of research on improving the quality and the effectiveness of health care.

Here, the political challenge is right in front of us: The House Appropriations Committee's proposed 2016 budget would completely eliminate the AHRQ, and sharply curtail other patient-centered research projects.