“The network thought this was an offensive show,” says lead actor Michael Richards in the DVD commentary for “The Outing,” a famous episode of the sitcom Seinfeld, wherein Jerry and George are misidentified as a couple by a college reporter. “And hence,” replies Jason Alexander, “why the big line was born, that became the catchphrase.”

According to the costars, the line “Not that there's anything wrong with that” was added to the show's script in response to concerns from above that the main characters’ too-impassioned denials of homosexuality might not sit well with the gay community. In addition to making it more palatable, catering to this sensitivity made the episode funnier; the line elevated it to legendary. While some aspects of “The Outing” now feel outdated due to legislative progress—a closeted soldier's reference to Don’t Act Don’t Tell, and a stand up routine that presumes that out, gay men cannot be married—the pleading urgency of the catchphrase still resonates deeply.

Similar concerns lie at the heart of an Amy Schumer sketch titled “Urban Fitters,” which has recently come under fire from Monica Heisey of The Guardian as emblematic of the comedian’s “shockingly large blind spot around race.” In the sketch, a hapless customer, played by Schumer, struggles to identify the salesperson that assisted her without using his race as a descriptor. At ThinkProgress, Jessica Goldstein reads the joke as being “on the white girl ... You cringe on her behalf.” That interpretation is endorsed by Schumer herself, but is oversimplified. While the exchange is indeed cringe-worthy, Schumer's portrayal isn’t entirely unsympathetic. As with Jerry and George, Schumer’s character is amusingly defensive of her own tolerance, and ultimately well intentioned.

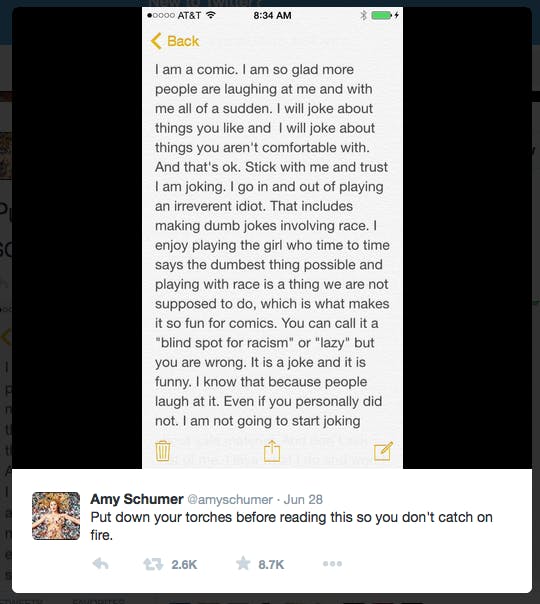

Yet it is precisely where Schumer's sketch hits the right notes that her uncharacteristically thoughtless response to Heisey's article falls flat:

Racism and homophobia are not binaries: They exist on a spectrum, as do tolerance and acceptance. It is perfectly understandable for well-meaning individuals to misstep when grappling with the complexities of sexuality and race.

But Schumer chose not to defend her comedy on these grounds, or apologize to those she offended. She seems to believe, instead, that if potentially marginalizing others is enjoyable and valuable to her, we should respect her desire to toe the line. She presents her humor's supposed shock value as having some kind of inherent worth in its edginess, failing to consider that, perhaps, most people are laughing because racism is rather mainstream after all. Schumer’s repeated characterization of a thoughtful, measured critique couched in an otherwise-fawning analysis as tantamount to a takedown suggests that she sees no place for politically minded criticism of comedy. The irony, of course, is that it’s Schumer on the warpath. She doesn’t want to engage in respectful dialogue with dissenting voices. She’d rather silence them.

This response is the signature of the successful modern comic’s victimhood complex, where those who have tremendous amounts of literal and figurative capital still feel persecuted by progressive culture. In a recent appearance on Late Night with Seth Meyers, Seinfeld complained that a joke based on a trite stereotype flopped, and attributed its failure to “a creepy p.c. thing out there.” “And this is a serious thing,” he bemoaned in an apocalyptic tone, “I can imagine a time when people say, well that's offensive to suggest that a gay person moves their hands in a flourishing motion, and you now need to apologize.” Yes, the dreaded day when a hugely successful comedian might be forced by standards of common decency to apologize to people far less influential than he for treating them in a cruel and insensitive manner. It sounds downright Orwellian.

While Seinfeld is complaining that no one is laughing, and Schumer is bragging that most are, it’s clear the two rely too heavily on audience cues as the metric of their jokes' merit—and in the process, they abdicate any non-professional responsibility. Schumer's disappointing statement stung so because she frequently and effectively tackles harmful social norms. Seth MacFarlane's impudence can amount to effective social satire when speaking truth to power, but veers toward the lazy and sadistic when mocking the powerless. Comedians seem to have no problem with political statements, so long as they pose no threat to their fun. “Look, I'm as forward-thinking as the next guy,” our creative icons seem to be saying, “but asking me to briefly consider the feelings of others and mildly alter my own behavior accordingly is One Step Too Far.”

Making people laugh is no easy task, which is why those who prove particularly adept at it are rewarded with fortune and fame. Those talented few that manage to bring audiences to tears while also tackling difficult issues with nuance and sophistication are rewarded critically in the form of GLAAD and Peabody Awards. At its best, comedy manages to do both: drawing mainstream attention to peripheral causes and changing minds en masse. It is perhaps because Schumer has continually, deftly reached these heights that she thinks the forces aren’t in opposition. A lot of the time, though, they conflict; it's far more difficult to make people laugh by challenging norms than by reinforcing them. The problem is that the laughter sounds the same either way.

When Schumer says that she enjoys people laughing with and at her what she means is that she enjoys people laughing with her and at the “irreverent idiot” she plays in many of her sketches. That tenuous distinction is what drove Dave Chapelle out of comedy: Were audiences laughing at the stereotypes his characters embodied, or were they laughing at the people those stereotypes were used to demean?

When Schumer, on-stage at the MTV Movie Awards, joked that Gone Girl was “the story of what one crazed white woman, or all Latinas do, if you cheat on them,”—in another instance Heisey flags as offensive—did she imagine the awkward titters that followed were at her “idiot” scapegoat or at Latina women? Were they laughing with or at Jennifer Lopez, an actual Latina woman in the audience, who seemed confused, uncomfortable, and relatively unamused?

After taking at face value Schumer’s claim, that the words spoken by her character are not representative of her views, Goldstein’s article hypocritically posits that Schumer’s comedic breadth is limited to the realm of her own lived experience. “I doubt the best way of addressing that fact is for Schumer to ... write jokes from a perspective she doesn’t have,” Goldstein writes. “It would likely be better for everyone involved if the industry at large dedicated more resources to cultivating and promoting the work of comedians [of color] who have lived that experience.”

Empathy and inclusiveness, however, are not mutually exclusive. Engagement in the “fight for all people to be treated equally,” is not a favor: It is a moral obligation. Privilege, be it straight, white, male, cis-gender, or upper class, does not lessen this duty. It only amplifies the obligation.

At the end of “Urban Fitters”, the cashier, wise to “Amy”’s ineptitude, purposely trots out the store’s four black male salespeople. “You really can't tell us apart?” one asks her; she eventually grows so flustered she runs out of the store. Schumer hopes to convince us she’s a different person than the woman she plays onscreen. Perhaps next time she makes a misstep, she’ll prove her good intentions by staying put and talking things out.