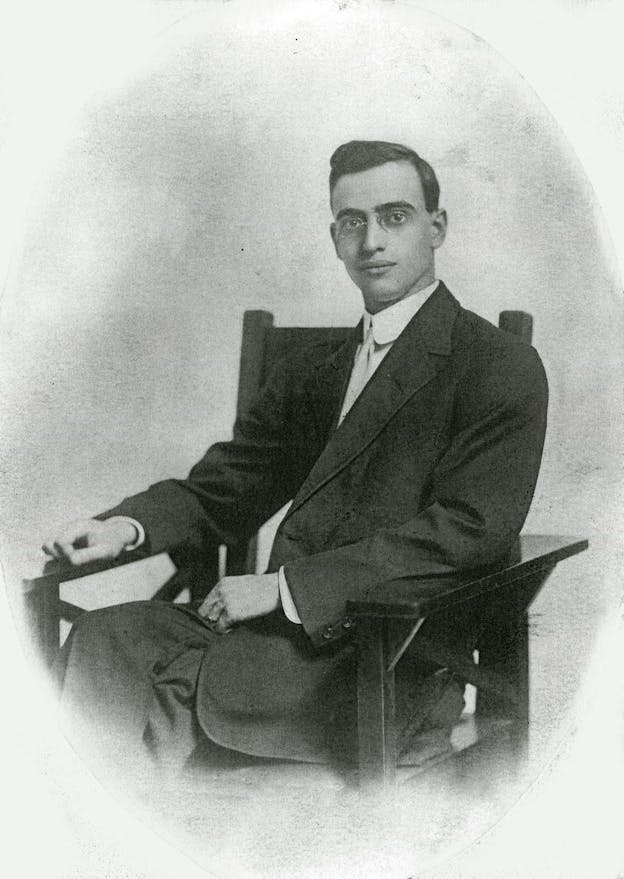

On August 17, 1915, exactly a century ago, Leo Frank, an Ivy League–educated Jewish industrialist, was lynched in the Atlanta suburb of Marietta. Although this was just one of 22 extralegal executions in Georgia that year, in the annals of vigilante justice it stands out. Not only was the crime premeditated—Frank was abducted from a heavily guarded prison without a shot being fired and driven 150 miles to a prearranged site—but its causes also foreshadowed the polarization that is crippling the country today. Then, as now, the media, both well-meaning and reckless, were capable of sparking national discord about regionally charged issues. Indeed, in the coverage leading up to the Frank lynching, one can hear the same righteous certainty that marks the coverage of such current disputes as that over the Confederate battle flag. The saga that came to a head with the Frank tragedy, far from being an ending, was in truth a beginning.

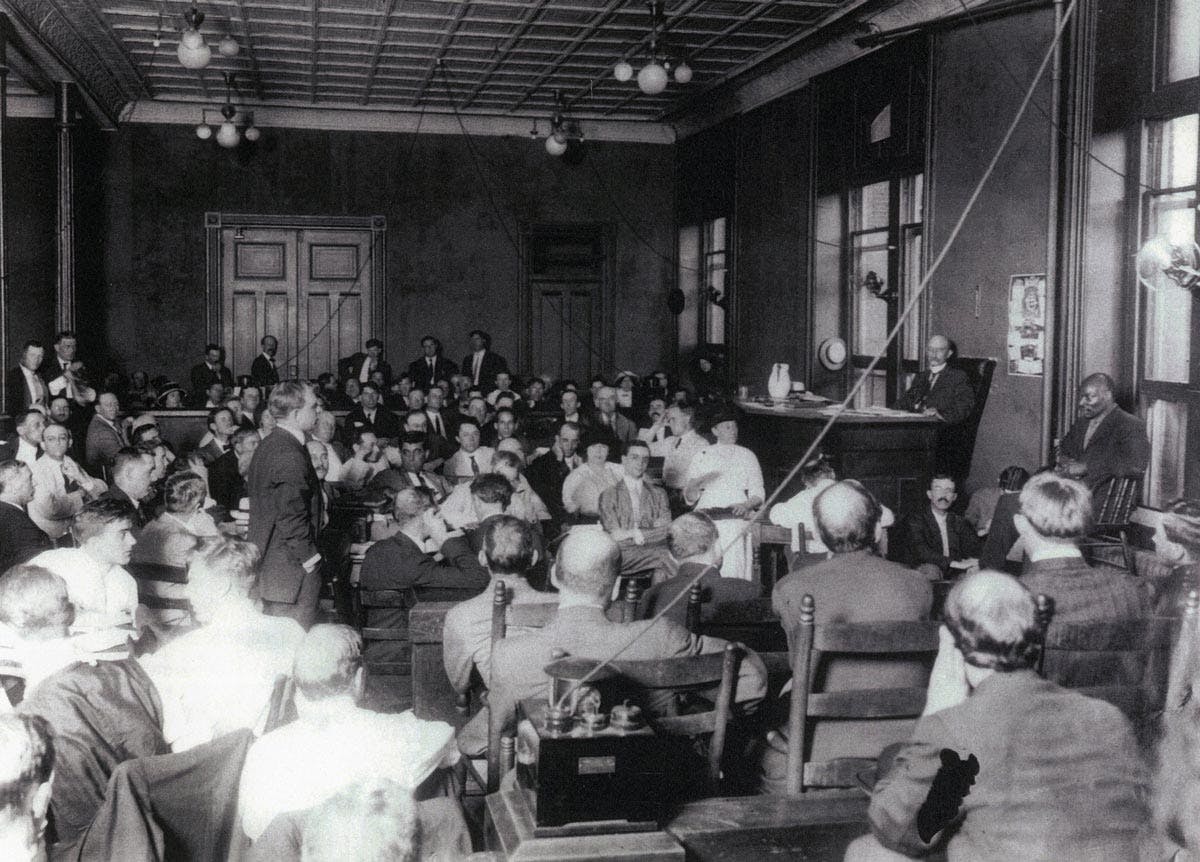

Frank had been convicted in 1913 of the murder of Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old child laborer from Marietta who toiled for pennies an hour at Atlanta’s National Pencil Company, where he was the superintendent. What made the case remarkable in the Jim Crow South was that the state relied chiefly on the testimony of Frank’s alleged accomplice, a black janitor named Jim Conley. According to Conley, Frank killed “little Mary” when she resisted his advances. In a strange and devastating aside that referred to circumcision, Conley added that Frank was “not built like other men” and was thus a devotee of oral sex, an act widely seen as deviant at the time. Under tough cross-examination, Conley’s account survived largely unscathed. “If the story Conley tells is a lie,” reported The Atlanta Georgian, “then it is the most cunningly clever and the most amazingly sustained lie ever told in Georgia!” An all-white jury believed the star black witness. Judge Leonard Roan pronounced the death sentence.

Frank’s lawyers appealed the verdict. Meantime, David Marx, the rabbi at the Temple, Atlanta’s Reform synagogue, sought the aid of three powerful northern Jews: Adolph Ochs, publisher of The New York Times; the influential advertising executive A.D. Lasker; and Louis Marshall, a constitutional lawyer. Citing courtroom applause when rulings went against the defense, remarks by the state attorney, Hugh M. Dorsey, emphasizing Frank’s supposed wealth, and Conley’s testimony, Marx convinced these men that the industrialist was the victim of anti-Semitism.

For nearly 18 months, The New York Times gave outsized attention to the story. Much of the news was generated by William Burns, a flamboyant private detective hired by Lasker to dig up new evidence that would exonerate the convicted man. The Times’ pieces typically did not include comment from the prosecution. By December 1914, a month in which the paper printed 33 articles and five editorials about the case under such headlines as “Georgians Urged to Plead for Frank” and “Georgia’s Justice Peculiar,” the affair had become a nationwide obsession. In fact, as other metropolitan newspapers, magazines, and filmmakers followed the Times’ lead, it became a cause célèbre.

The exertions of Frank’s Northern allies ignited a Southern backlash. The most incendiary voice belonged to Tom Watson, a former U.S. congressman from Georgia and the editor of The Jeffersonian, a popular, tabloid newspaper that promoted agrarianism and denounced the financial elite. Watson had started his career as a reformer who flirted with racial integration (black leaders frequently shared a platform with him). Over time, however, he’d suffered political reversals that led him to pursue a career as an unreconstructed and bigoted polemicist. Beneath such banners as “The Frank Case; the Great Detective; and the Frantic Efforts of Big Money to Protect Crime” and “The Frank Case Still Raging in Northern Papers,” Watson used The Jeffersonian to lambaste supporters of the “lecherous Jew.” In accusing them of whitewashing facts, “insulting the Gentiles of this country,” and disrespecting Dixie, Watson descended into demagoguery. The circulation of The Jeffersonian more than tripled. The issue was no longer Frank’s guilt or innocence but perceived cultural grievances.

Against this backdrop Louis Marshall made a final appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, relying on a novel use of the Fourteenth Amendment that would later become accepted. Following a seven-to-two decision against Frank (the dissenters were Oliver Wendell Holmes and Charles Evans Hughes), the case returned to Georgia, where it landed on the desk of Governor John Slaton. Although Slaton was saddled by a conflict of interest—he was a law partner of Frank’s lead counsel—he commuted Frank’s sentence to life imprisonment in June of 1915. The New York Times cheered. Watson was furious. “Jew money has debased us, bought us, and sold us—and laughs at us,” he wrote in The Jeffersonian. “Hereafter, let no man reproach the South with Lynch law; let him remember the unendurable provocation; and let him say whether Lynch law is not better than no law at all.” Thus spurred, the leading citizens of Marietta orchestrated the deadly last act.

In the aftermath of the lynching, Frank’s advocates essentially dropped the case. At The New York Times, many editors believed the paper had endangered its reputation for objectivity. “So perishes a great enthusiasm, for the sake of the N.Y. TIMES,” Ochs’ assistant wrote in his diary. Ochs felt responsible for Frank’s fate, as did Lasker. Frances Lasker Brody, the ad man’s daughter, told me her father was guilt ridden. He feared that he had exacerbated a bad situation. Watson experienced no such regrets, declaring: “A Vigilance Committee, instead of the sheriff, carried out the sentence.”

Historical research has all but proved that Frank was innocent of the Phagan murder and that the killer was Conley. He had the motive (robbery) and the opportunity: Drunk and in debt, he was lurking in the lobby of the National Pencil Company on the afternoon of the crime when the girl exited Frank’s office with her pay: $1.20.

The societal reverberations were many—and less tidy. Three months after the lynching, the Ku Klux Klan reemerged from a 45-year quiescence to conduct its first twentieth-century cross burning atop Georgia’s Stone Mountain. Simultaneously, the Anti-Defamation League, which was founded in 1913, began to fight anti-Semitism aggressively. There could be no greater opposites than the KKK and the ADL, but they are just two of the divisions that arose from the Frank case. The South was guilty of a horrific moral wrong and in the aftermath closed its eyes to the lynching. There was only a mock investigation, and five years later Watson was elected to the U.S. Senate. The North, however, was guilty of imperiousness. Frank’s mainstays were less interested in being effective than in being right. The Times, far from persuading opponents of the Jewish industrialist that he was the wrong man, only reinforced their worst instincts. Ten decades on, amidst resurgent debates in journalistic echo chambers about the unfinished business of Southern history, it all feels worrisomely familiar.