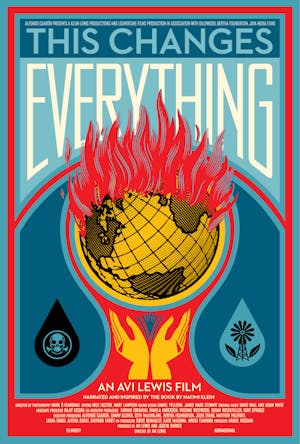

Last year, Naomi Klein’s book This Changes Everything laid bare the capitalist economic system’s dependence on environmental devastation. We can’t fight climate change until we properly understand capitalism’s culpability, she argued. And with her characteristic brand of activist-oriented problem solving, Klein suggested we could seize this moment of climate crisis to revamp our addled global economy. A documentary of the same name, directed by Klein’s husband Avi Lewis, was conceived as a parallel project to Klein’s book and had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival last month. It trumpets the same battle cry: that fighting global warming effectively means overturning capitalism. As politicians keep bickering over absurdly modest measures like cap-and-trade programs and scientists continue to announce startling figures of shrinking glaciers, Lewis and Klein’s message feels as urgent as ever.

Klein is really good at making radical arguments like this one terrifically accessible. This Changes Everything is the third book in Klein’s anti-globalization trilogy, following 1999’s No Logo, which criticized brand-oriented consumer culture, and 2007’s The Shock Doctrine, which chronicled how corporations take advantage of disasters to implement free-market policies designed to enrich a small elite. The film This Changes Everything marks the second time that Klein and Lewis have collaborated on a documentary. Eleven years ago, the pair made The Take, a movie that followed a group of autoworkers in Argentina who took over their factory and turned it into a cooperative. Lewis and Klein’s new film is similar in its aim to promote grassroots anti-capitalist action.

“A book can’t help you from feeling isolated and alone. A film, I think, can,” said Klein when I caught up with her and Lewis in Toronto to talk about the documentary. This Friday, it will be released in select theaters in New York, and will roll out in Los Angeles and Canada soon afterward. In the film, Klein’s thesis—that the climate crisis is inextricably tied to our rotten economic system—is woven together with portraits of activists fighting against mining and energy projects everywhere from Canada to Greece to South India. Like the book, the film succeeds in making a rigorous argument intelligible to a wide audience. By mixing essayistic filmmaking with vérité documentary techniques that showcase the stories of regular people turned activists, This Changes Everything also communicates an emotional urgency perhaps best suited to the cinematic medium. The documentary connects the past and the present, historicizing the activist battle against new coal plants and oil wells.

Klein traces the ideological infrastructure our current petrochemical economy is founded on back to the Enlightenment period. “It’s a moment in history where you have the Scientific Revolution and you also have the colonial project overlapping temporarily. The idea of infinite growth begins and there’s the birth of the machine,” she said. “These are all happening in the very same century.” She thinks drawing attention to when and where these concepts came from is intrinsic to developing alternatives to them. “Calling it human nature erases that it comes from a place. There are other ideas and other ways of relating to the world.”

From the indigenous tribes affected by Tar Sands development in Alberta to the South Indian villagers protesting a proposed coal plant, the documentary shows communities that practice non-capitalist ways of relating to nature. They’re all suspicious of the narrow post-Enlightenment idea of progress that fossil-fuel development promises. They don’t see the industrial extraction of resources as a necessary pit-stop on the way to an advanced society, but are rather see polluting resources like water which sustain human life as backward.

Klein uses these communities as examples of alternative ways of relating to the environment. She refutes the idea that we are doomed because it’s human nature to live in an environmentally destructive manner. A tendency to generalize “human impact” is embedded in terms like the anthropocene, Klein noted, which is the scientific designation for our era—it refers to the epoch in which human activity from industrial farming to resource extraction has irreversibly changed the planet. Basically, you can read our impact in the rocks of Earth itself. “It being ‘the age of man’ diagnoses the problem as being something essential in humans and glosses over the fact it’s not all humans,” Klein said, noting an essay on the subject by Andreas Malm from Jacobin magazine. “[Malm] makes the argument that it’s only a very small subset of humans that came up with the idea of burning fossil fuels on an industrial scale, and it’s still a minority of humans who do so.” For example, the average American consumes 500 times more energy than the average person living in a country like Ethiopia or Afghanistan. And even within the U.S., there are inequalities.

Environmental issues are inextricable from issues of economic and racial justice. “Being in New York the week after Sandy, there were powerful and disturbing flashbacks to being in New Orleans a week after Katrina happened,” said Lewis. For them, they said, the 10-year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina this year connected the racial justice movement and the climate movement for many. “I think that because Black Lives Matter has united that conversation in the U.S., and then having the Katrina anniversary, for a lot of people it was a bit of an ‘oh yeah’ moment,” Klein said. “If you have a system in which black lives are treated as if they don’t matter, when you layer climate change on top of that then you see the issue on the mass scale.”

While Lewis and Klein’s documentary doesn’t focus on Hurricane Katrina or the intersection of American racial justice and climate change in particular, it does outline how the current economic system values some lives more than others. Klein’s narration returns over and over again to the idea of “sacrifice zones”: A resource economy depends on certain areas being disproportionately ravaged by extraction and processing—these places and the people in them are seen as worth sacrificing for some nebulous concept of the greater good. Populations in sacrifice zones have often been disproportionately poor and people of color, but in the film, we see that as the zones keep expanding middle-class white people from Montana to Greece are realizing they’re new targets of exploitation.

The emotional core of the film comes from individuals battling against being seen as disposable. Though as filmmakers Lewis and Klein unpack troubling realities, their film is cautiously optimistic, and focuses on the power and potential of these grassroots movements. We need a new system, in their view.

While the film concentrates its attention on citizen-driven actions, Klein also spearheaded the policy-focused Leap Manifesto, which was just released in mid-September in advance of the Canadian election, which takes place on October 19. “It’s basically a roadmap for Canada to get off fossil fuels,” explained Klein. Its signatories include public figures like environmentalist David Suzuki and folk-rock icon Neil Young.

Though Lewis and Klein are hopeful, they’re also realistic. Talking to them about the most recent price shocks—which happened since they wrapped shooting, and which have caused the price of oil from the Alberta Tar Sands to fall to historic lows—Lewis notes that “it is not affecting oil company profits as much as you might think it is.” He continued. “There are projects that have been suspended, but there’s thousands of barrels of new capacity that’s going ahead in Alberta each day. It’s not expanding as fast as they want it to, but it’s still expanding.”

Still, Klein explained the price shock is an opportunity. “Here is a pause in the frenetic energy. That kind of money makes it really hard to think. It’s hard to think with oil at $100 a barrel,” she said. “But now we have a moment where we can look in the mirror, and ask is this the best way to run the economy?” Her answer? No.