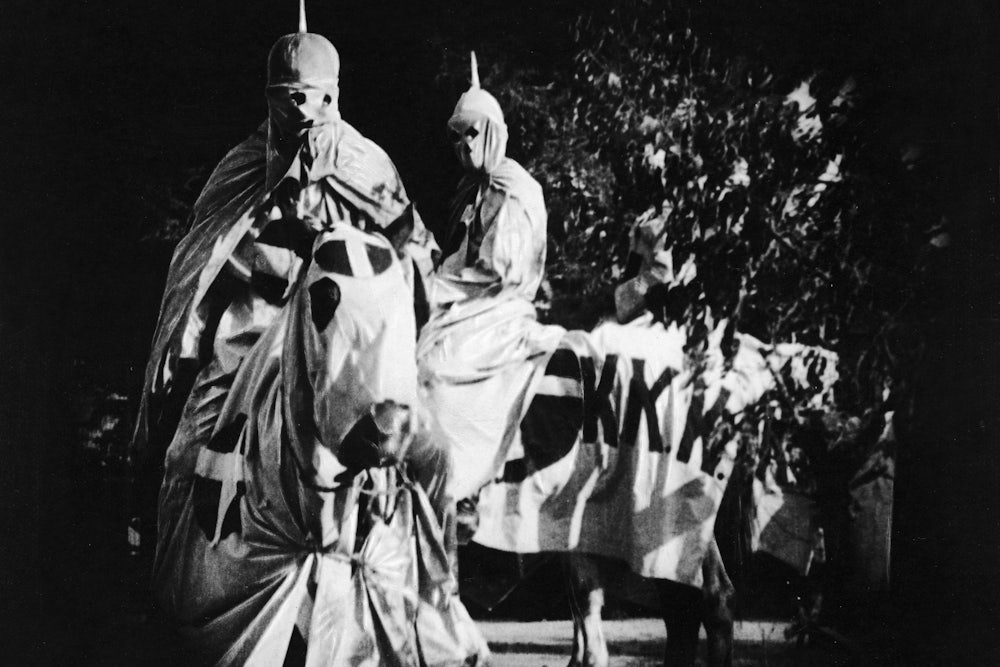

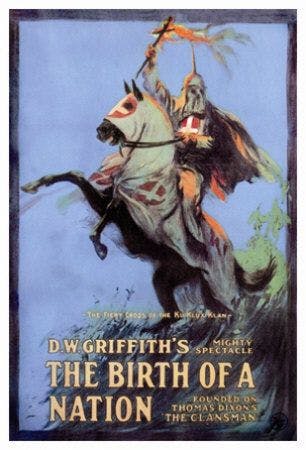

An advertisement appeared in the Atlanta Journal for “The World’s Greatest, Secret, Social, Patriotic, Fraternal Beneficiary Order” on December 9, 1915. Next to this advert for the newly reformed Knights of the Ku Klux Klan was a poster for the film The Birth of a Nation, which celebrated and memorialized the original Klan and was just beginning its record-breaking run in the city. Three days earlier at the premiere, members of the Klan had reportedly paraded outside the theatre.

A century on and the dark days when the Klan recruited millions of members across America to its divisive and racist creed may seem like history, but the rise of anti-immigrant sentiment around the world and recent proclamations from the likes of Donald Trump—who has said he wants to ban all Muslims from entering the U.S.—are a sobering reminder of how the media can be used to spread division in society.

The Klan knew how powerful an institution the fast-growing movie industry was going to be and, while historians have recognized the link between D.W. Griffith’s hugely controversial film and the reformed Klan, what is less well known is the broader way in which the Klan used film over the next decade to recruit members, generate publicity, shape public behavior and define its role within American society.

At its height in the 1920s, the Klan had an estimated 5m members and oversaw a massive publicity operation. It was publishing dozens of weekly newspapers. It was producing films and radio shows, owned theaters and staged large-scale community plays. It had its own bands and baseball teams, a university, a successful women’s group and a strong presence in local protestant churches.

Klan groups set up film companies and produced their own feature films during the 1920s, such as The Toll of Justice (1923) and The Traitor Within (1924). As part of the Klan’s efforts to position itself at the heart of local communities, these films would play in churches, schools, Klaverns (Klan buildings) and at outdoor events. Posters advertised Klan values as much as the film itself, with slogans such as “Do away with the underworld” and “Protect clean womanhood”, while often identifying the Klansman as “100 percent American”. Indeed advertisements for The Toll of Justice presented “The picture that every red-blooded American should see”.

These Klan productions would also play in cinemas owned or run by Klansmen. For example The American theatre in Noblesville, Indiana once advised patrons that they could come to the film “before or after the K.K.K. parade tonight” and used the three Ks to describe its premises as “Kool, Kozy, and Klean”.

A war against “immorality”

The Klan’s own films were often intended to “counteract” what the Klan saw as “immoral” mainstream productions. These criticisms helped the Klan to project its own religious and social values to a wider public, often aligning itself with more established groups. It launched a strong campaign against The Pilgrim (1923), in which Charlie Chaplin plays a convict who pretends to be a protestant minister. This helped to get the film banned or cut in a number of states.

The Klan objected to the actress Pola Negri’s “low ideals of womanhood” in Bella Donna (1923). The following year it took on Paramount Pictures’ “sex plays”, objecting to titles such as Manhandled, The Enemy Sex, Changing Husbands and The Female—which promised to show Betty Compson “more nearly nude than she has yet appeared on screen”.

Yet its main criticisms of these Paramount films were reserved for the producers and the film industry. This is all too evident in the relevant Klan pamphlet, which was titled: “Jew Movies urging sex vice: Rome and Judah at work to Pollute Young America”. A few years later, in 1933, the Klan publication Kourier ran an article on Jewish film producers which concluded that: “Hollywood certainly needs a Hitler!”

In decline

Yet by the 1930s the Klan was increasingly marginalised, which is partly reflected in Hollywood films of the era. The late 1930s saw a cycle of “social problem” films directly exposing Klan activities. In 1937 the Klan filed a lawsuit against Warner Bros, objecting to the appearance of the “Klan insignia” in the Humphrey Bogart film, Black Legion. The Klan demanded $500 for every time the picture had been shown and $100,000 in damages. It lost the case, but gained a few valuable column inches.

Two years later, producer David O Selznick cut all mention of the Klan when he adapted Margaret Mitchell’s novel, Gone with the Wind, for the big screen. Mitchell had presented the original Klan as honourable and necessary. The Klan press condemned this edit by complaining that “Jews will even stoop to … distortion of history to carry out their propaganda”. The Klan still sought to align itself to the film, though. It contacted MGM, offering to parade outside the Atlanta premiere, just as it had done 24 years earlier with The Birth of a Nation. The offer was dismissed out of hand.

While the Klan would never again exercise such influence through film and the media, the example serves as a reminder of how a small group reformed in Atlanta 100 years ago used the entertainment industry to become one of the most influential and recognisable social and political forces in the country.

It would be foolish to dismiss this as the stuff of history—the Klan’s fearmongering around the themes of immigration and “The Traitor Within”, begin to look depressingly familiar when you look at the proclamations of the likes of Trump and the media organizations only too happy to give him a platform—Fox News being the most obvious example. We always need to keep a close eye on what the media tells us is “normal” and how it projects national identity.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.