Terrorism has pushed the economy to the margins of the 2016 debate—and off the stage entirely at Tuesday’s Republican debate. But the Federal Reserve’s decision on Wednesday to raise interest rates for the first time since 2006—an action that risks putting a damper on growth—served as a reminder that the economy may well return to the top of voter’s minds next year. The rate hike is very likely to figure into Saturday’s Democratic debate; Bernie Sanders, who’s built his campaign around a populist message about economic discontent, immediately denounced the decision as a premature step for a weak economy.

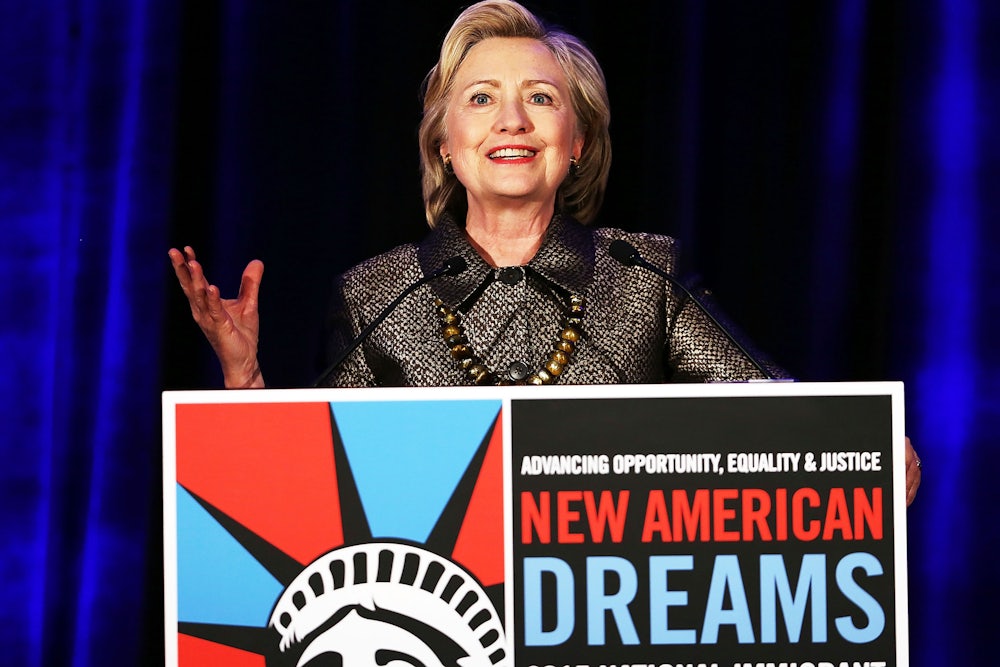

So far, Hillary Clinton has been silent about the Fed’s action, though she’s previously downplayed the move, saying that global markets have “already processed” a step that the central bank has long signaled that it would take. How she responds on Saturday night will be a key moment to watch, as the issue highlights a vexing political conundrum that the party’s frontrunner is likely to face in 2016: Clinton, as the nominee, would fare best if the economy is in good shape going into November, but she has also embraced a populist message that speaks to the deep economic grievances that most Americans—whatever the Fed thinks—are still feeling.

The Fed’s decision to raise rates from near zero was based on its conclusion that the economy is in good enough shape to handle higher interest rates, which are meant to ward off inflation down the road and minimize disruption to financial markets as the economy continues to pick up speed. The rate hike is an acknowledgement of “the considerable progress that has been made toward restoring jobs, raising incomes and easing the economic hardships that have been endured by millions of ordinary Americans,” said Fed chair Janet Yellen.

If the central bank is right—both in its fundamental assessment of the economy and in the timing of its decision to raise rates—it should be a boon to Clinton’s prospects against whoever emerges from the Republican scrum with the nomination. To be sure, the Fed described its rate hike as a pre-emptive, very gradual step intended to support an economy whose recovery is “not complete,” as Yellen put it. But it is a vote of confidence that considerable economic progress has been made: It’s no coincidence that the Fed made its decision after wages finally started showing signs of picking up in a tighter labor market.

For all the anger, disillusionment, and discontent that Americans feel about the political system, their economic outlook has gradually begun to improve: According to a new Gallup poll, 42 percent of Americans in 2015 said it was a good time to find a quality job—the highest number since 2007. But that perspective remains sharply divided along party lines: An October Wall Street Journal poll showed that 47 percent of Democrats say they feel “cautiously optimistic about the economy,” compared to just 4 percent of Republicans.

Those fundamental attitudes may ultimately matter more than any individual controversy or news cycle: A large body of research shows that voters are more inclined to stick with the incumbent party when the economy is doing well and to support the opposition when it’s not. Recent elections have borne this out. An economic downturn in the months leading up to the 1992 election sunk George H.W. Bush’s re-election prospects, and the beginning of the financial crisis under his son, George W. Bush, helped Barack Obama win the White House in 2008. By contrast, economic booms boosted both Bill Clinton and Ronald Reagan to re-election.

Political scientists, moreover, have found a strong correlation between rising personal incomes and the incumbent party’s percentage of the vote. So if things are looking up as we head into next fall, Clinton would be well positioned to run on Obama’s economic record and promise to expand the prosperity to the middle class—the Clintonian campaign message that she seems to be most comfortable with.

If the Fed made the wrong call, however, we could see a slowdown in job growth and business activity. That would be bad news for the Democratic nominee on two counts: It would mean that the economy isn’t actually strong enough to handle higher rates right now, and that a slump could be setting in just as many voters are finally tuning into the election and heading to the polls. Sanders is already warning of that, issuing a statement on Wednesday that slammed the Fed for making a poor assessment of the economy and acting prematurely. “When millions of Americans are working longer hours for lower wages, the Federal Reserve’s decision to raise interest rates is bad news for working families,” he said. “The Fed should act with the same sense of urgency to rebuild the disappearing middle class as it did to bail out Wall Street banks seven years ago.”

Sanders’s response is no surprise; economic discontent is the very fuel of his populist campaign. But for Clinton, who will almost surely be the nominee who must confront the economic trends in 2016, framing an economic message is considerably trickier. Even the best-case scenario for Clinton—one in which the economy is not only growing but booming in the months leading up to Election Day—bumps up against yet another dilemma for her, and for the Democratic Party writ large.

During the Obama era, Democrats have made the fight against inequality a central focus. And while Clinton doesn’t bring the populist heat like Sanders—it’s just not her style—her domestic platform hinges on using higher taxes on the wealthy to help the struggling middle class, and she has framed her economic message in more stridently populist terms than most political observers would have expected. The political risk is that this message could amplify the broader feeling of pessimism about the economy and a declinist view of the country—and could end up adding even more fuel to, for instance, a certain Republican candidate’s call to Make America Great Again.

Simon Rosenberg, a Democratic strategist who worked on Bill Clinton’s campaigns. “If Democrats cannot convince the American people that this progress is due to their approach, there just isn’t going to be a compelling reason to vote Democratic next year.”

But it’s not quite so straightforward: If Clinton sounds too sanguine about the economy, it will risk making her seem out of touch with the very real economic discontents of ordinary Americans.

From her first big speech on the economy in July, Clinton has toggled between two messages: On the one hand, she’s touted the economic achievements of the two most recent Democratic presidents, praising her husband for overseeing “the longest peacetime expansion in our history,” and Obama for having “pulled us back from the brink of depression.” On the other hand, she’s wielded more populist rhetoric that laments the current state of the economy. “It’s not delivering the way that it should. It still seems, to most Americans that I have spoken with, that it is stacked for those at the top,” she said, shortly after her campaign launch.

How do you run a campaign that capitalizes on the country’s populist mood—and anger—while also touting the economic advances made under Obama? On Saturday, we may get a glimpse of how Clinton will try to blend those two strands into a message for the general election—which she’s clearly gearing up for. Thus far, she has attempted to unify the rather disparate messages into a call for a “growth and fairness economy”—allowing her to celebrate the gains while acknowledging the serious need for longer-term fixes.

But while that may sound like a reasonable strategy, the politics are thorny. We are not in an optimistic moment right now as a country, and given the dynamics surrounding incumbency, Republicans are better positioned to exploit Americans’ worries and grievances. While Clinton has built her campaign around greater economic security for the middle class, she’s likely to have a better shot if voters are already feeling more hopeful about the health of the economy as a whole—or if she can manage to convince them of it.