If there were no Truman Capote, the film of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (assuming that it could have existed anyway) would be a satisfactory sentimental comedy, much like the ones that Jean Arthur used to make. But hulking over it is the fact of the author, the Littlest Giant since Stephen A. Douglas, whose quality sternly underscores some shortcomings in the picture.

Those who have read Capote’s short novel may have liked it well enough. Those who have re-read it (as I have) may like it a good deal more than that. It seems now a finely turned work and, excepting the romanticism about bartenders that afflicts New Yorker writers and alumni, every sentence, every phrase sounds inevitable, flavorful, apt. It lacks the larger resonance of the work with which it has been very often compared—Isherwood’s “Sally Bowles”; but it is a vivid memoir of an interesting girl who seems to have left the author wishing he could find a way to use her, at last perceiving that there was nothing to do but portray her.

The film adapter, George Axelrod, has used her. He has tidied her language and behavior, built her a nice symmetrical plot, converted the observer-narrator into a boy friend, inserted cute scenes like the one where they go into Tiffany’s to get a cheap ring engraved, teased out several elements in the book so that the ends could be tied in neat knots, and in general has tailored Capote’s astringent, truthful tale into a slick movie. But it is slick; and since, for American films, this is a lean year (decade? century?), let us count our mixed blessings.

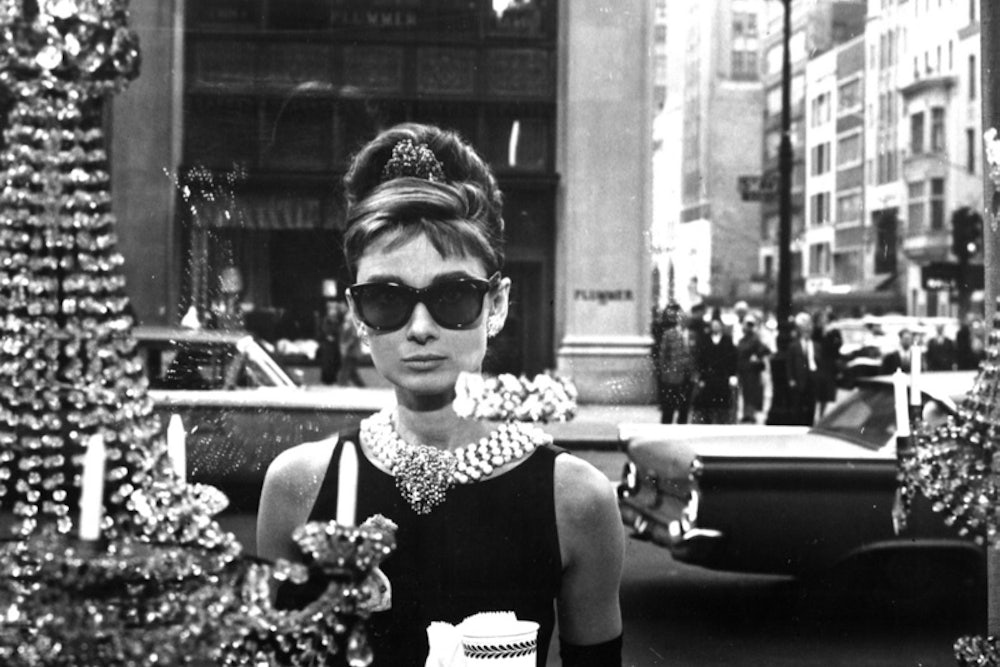

As Holly Golightly, the female cavalier of café society, Audrey Hepburn is perfectly cast but performs somewhat less than perfectly. Her beautiful piquancy and talent are no less than ever, but either her director here has not as keen an ear as he ought to have or else Miss Hepburn (always a possibility with big stars) is not quite manageable by any except famous directors. At any rate, in the opening sequences, her readings have an unwonted lack of color and conviction and her performance lacks the easy control that makes some of her films re-visitable. These early sequences may well have been filmed last, but the effect is as if she had got a firmer grip on the part as she went along and brought it into sharper focus. Perhaps it was the American accent that worried her. Nevertheless I cannot think of another actress I would have preferred in the part.

George Peppard, as the young writer, is pleasant and credible, an eminently useful player in films. He is the newest exponent of the Fonda-James Stewart factor, the boyish man who is our national ideal, strong but reticent, with the suggestion that he has a piece of mom’s apple pie tucked away just out of sight and that no matter how much he likes writing and girls, what he would like best is to be back at the old swimming hole with the gang. But this quality is natural to Peppard, not contrived; and combined with his competence, should carry him far.

Patricia Neal, the rich wife whose gigolo he is, has an unsatisfactory part on which she brings too much to bear; they have sent a woman to do a girl’s job. Martin Balsam, a solid and satisfying naturalistic actor, plays a Hollywood agent, the part in which Axelrod has added his best touches to Capote. Mickey Rooney is made up for Mr. Yunioshi—and plays him—like a Hearst wartime anti-Japanese cartoon.

Blake Edwards is a director of ability who seems at present not quite sure of himself. The cocktail party is as excellent as if Billy Wilder had done it, but Holly’s visit to Sing Sing just misses the comedy as Wilder would not have missed it. In striving for a style, Edwards includes two high overhead shots of a bed where one would have been superfluous; he has been bullied into including irrelevant “star” close-ups of Miss Hepburn; and his handling of the last scene in the rain is no fresher than the conception and the writing. But his work has flashes of bright possibility throughout.