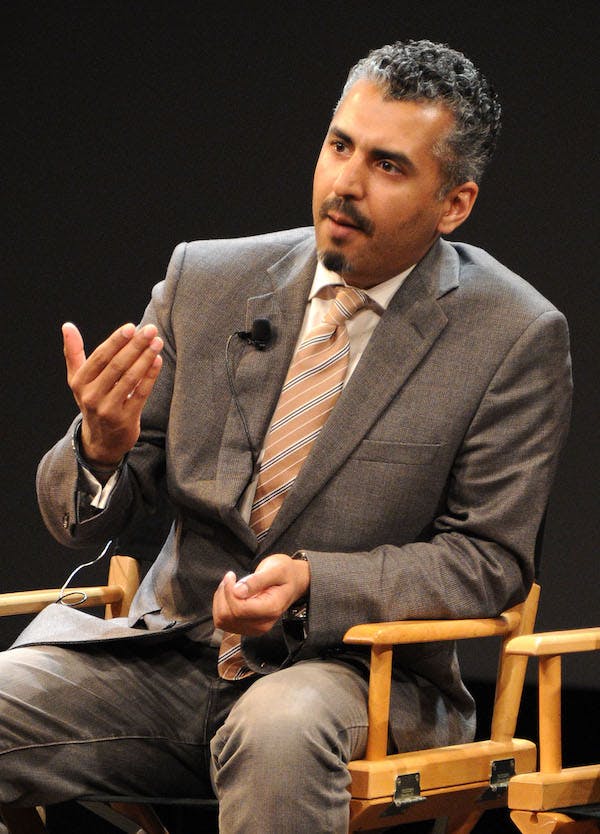

Maajid Nawaz’s shoes clack against the hardwood floor as he ambles up and down the center aisle of the Oxford Union’s hallowed debating chamber. It’s January 2013 and the British activist, sporting a slick black tuxedo and a gelled coiffure, urges the House to accept the motion that the American Dream is a noble ethos to which all people should aspire.

By his account, he should be on the other side of the aisle. “For 13 years of my life, I considered America my enemy,” he says, rehashing the events that marked his discipleship with Hizb ut-Tahrir, or “The Liberation Party,” a pan-Islamic political organization that aims to establish a global caliphate through non-violent means.

The self-described former “radical” joined the group’s British chapter when he was 16. It was during his four-year stint in the bowels of an Egyptian prison last decade, he says, that he began to reject the dogma of religious extremism that landed him there, and came to embrace the values of liberalism that now define his public profile.

Today, instead of supporting the cause of Quran-thumping diehards, he’s ingratiated himself in the growing union of neoconservatives and hawkish liberals who believe in Western exceptionalism and the efficacy of power, especially military power, to expand its influence and protect its interests. He has found in them an opportunity to expand his platform, and they, in him, a veneer that deflects accusations of Islamophobia and Western triumphalism by fixating not on Islam per se but on the alleged threat posed by its foreign “ism” affix: Islamism.

Against the backdrop of ISIS beheadings, Syria’s downward spiral, and rising fears of domestic terrorism, Nawaz’s story has made him a go-to commentator in American print and television media. Following the Paris attacks in November, he strolled through the streets of the French capital with CNN’s Anderson Cooper, explaining the need to confront the religious species in the genus terrorism. On Fox News’s The Kelly File, Nawaz warned of a “global jihadist insurgency,” and, to the delight of network devotees, lambasted Obama’s strategy to defeat the Islamic State as one of obfuscation, denial, and inaction. Nawaz is also a contributor to The Daily Beast and the author, with neuroscientist-cum-atheist-celebrity Sam Harris, of the book Islam and the Future of Tolerance, published last fall by Harvard University Press.

The 38-year-old Liberal Democrat has worked his way into the world of think tanks and national security circles, too, mingling with thought leaders and politicians who believe that his journey from fundamentalism to freedom gives him the authority to opine on a broad range of topics related to religion and violence. Nawaz jet-sets from Ivy League lecture halls to annual gabfests in the Colorado mountains; from the stages of TED talks to awards galas; and from the backrooms of British officialdom to Senate hearings in Washington, recounting at each juncture along the way the narrative that undergirds his rise to fame: a foot soldier of a Western enemy whose march toward an Islamic caliphate was interrupted by a Damascene conversion.

Buried beneath the adulation, though, are the sighs of those who have long maintained that Nawaz’s dramatic tale of redemption isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be. Interviews with his friends and relatives suggest that his account is riddled with inconsistencies and inaccuracies—indications, they say, of a turncoat who cares more about being a well-compensated hero than he does about the cause he champions.

“Most in my family who witnessed his life outside home, religious or irreligious, find his story at least exaggerated or embellished for his agenda, if not absolutely false,” Nawaz’s elder brother, Kaashif, said.

Ashraf Hoque, a friend from Nawaz’s college days, is more blunt.

“He is neither an Islamist nor a liberal,” he said. “Maajid is whatever he thinks he needs to be.”

Nawaz was born in 1977 in Essex, England, the son of an electrical engineer from Gujrat, Pakistan, and a mother that was determined to raise her kids on a steady diet of Western literature. He spent his early years in the mostly-white resort town of Southend, where he ran with a crew of striplings that clashed with the neighborhood skinheads. He was an affable guy, his friends say, though with an arrogant streak—a charismatic charmer who yearned for a platform of empowerment and found it in the fundamentalist Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Those rhetorical skills helped Nawaz ascend the group’s ranks to become a national speaker, “one of the most effective recruiters in the organization,” he averred in his 2013 memoir, Radical. Driven by his anger over the persecution of Muslims around the world, he labored to grow Hizb ut-Tahrir, and to that end hoped to revive the party in Egypt, where it had crumbled after a failed coup attempt in 1974. He didn’t get too far. In April 2002, he was arrested at gunpoint in Alexandria and hauled off to the Mazra Tora Prison.

Nawaz, who didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, has said many times that those four years in prison changed his beliefs. A year after his release, he told the New York Times in 2007 that his “doubts about Hizb ut-Tahrir crystallized” during that time. “I changed in prison,” he said in 2014. “My heart softened,” he told an Australian outlet recently. “Not everyone reacted that way to the brutal conditions we were held in, but it did kind of lead to my own maturity so that by the time I was released, I found that I could no longer subscribe to the ideology.”

That intricate dance nags Ian Nisbet, who spent four years in prison with Nawaz—three in next-door lockups, one in a group bunk. It wasn’t apparent to him that his cellmate was ever engaged in a tug-of-war with his moral conscience. “There was never a moment that Maajid had anything good to say about secularism in the prison,” said Nisbet, who remains affiliated with Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Nisbet remembers Nawaz as a guy who wasn’t particularly religious, but labored to appear committed to Islamism in an effort to win popularity and promotion. And so, Nisbet says, Nawaz passed his days scouring religious texts for winning arguments and made it his personal mission to triumph over anyone who dared to offer an alternative view of God’s plan. “He also wrote out [our] press release on the plane ride home,” Nisbet recalled.

Nawaz’s cousin, Yasser Nabi, visited him in prison on several occasions. He didn’t notice that Nawaz’s conviction had been rattled, either. Instead, Nabi says, Nawaz spoke with a sort of pride at being incarcerated with would-be terrorists, and even evinced an uncharacteristically extreme side. “In prison, Maajid and I spoke about many things and what was clear at the time was that his views had changed very little,” Nabi said. “In some ways, he became more jihadist in certain things. … Our discussions did not indicate any kind of push towards liberalism.”

On February 28, 2006, Nawaz and his prison mates were granted an early release, and returned home the next day to a throng of supporters at London’s Heathrow Airport. Family urged him to take a break and rebuild his life. But rather than cast off the yoke of religious fundamentalism, he tightened it and championed the cause of Hizb ut-Tahrir for more than a year after his return to Britain.

“He was 100 percent committed to [the group] when we left [prison], as we discussed it almost every day,” Nisbet said.

At a press conference after his discharge, Nawaz said, “I have become more convinced of the ideas that I went into prison with.”

On the BBC’s HARDTalk he urged the establishment of an Islamic caliphate as soon as possible. In January 2007, four months before Nawaz left Hizb ut-Tahrir, he was on the front lines of its protest outside of the United States embassy in Grosvenor Square, condemning colonialist aggression of Western governments and demanding the rise of a global Islamic State to counter it.

“If he were having doubts upon his return to the UK, and was leaning towards secularism, it would be reasonable to expect some manifestation of this doubt—perhaps a softening of his views, some internal dissent around the margins,” said AbdusSabur Qutubi, one of Nawaz’s friends in his youth who left Hizb ut-Tahrir in 2006. Qutubi, whose surname is a pseudonym, met Nawaz outside of the Regent Park mosque after his release and found him more hardened than ever. Britain, Nawaz told him, was an “active land of war,” and as a Muslim in a non-Muslim land, he was not beholden to its laws. “For someone who was losing confidence in political Islam and [Hizb ut-Tahrir], and considering liberalism as an alternative, taking an about-right turn is not indicative of this,” Qutubi said.

But Nawaz’s story hasn’t been consistent. While sometimes spinning a narrative about a cellblock-born conversion, at other times he has said it was hard to leave—that he couldn’t just bolt from an organization that had been his moral compass for so long. “It’s not like a tap you can just switch off,” he wrote in Radical.

Nawaz guided Ashraf Hoque through the ranks of Hizb ut-Tahrir. They were “inseparable” friends, like brothers, Nawaz wrote. Today, things have changed. Hoque says that Nawaz was “confused” after he left prison but not because of a profound ideological shift. Rather, he told me, Nawaz realized that the fire and brimstone brand of religious conservatism that had won him celebrity status among Islamists couldn’t guarantee him the future of grandeur he wanted after his return to the U.K. He had an “insatiable lust to be recognized,” Hoque said.

By Nawaz’s own admission, moving further up the Hizb ut-Tahrir hierarchy was not possible. “It took me another, roughly, ten months to come to the conclusion that I actually indeed had no place left on the leadership of this group,” Nawaz said in a 2013 interview with NPR. “And so, in 2007, I think I unilaterally resigned my position from the leadership.”

His timing was curious. Nawaz broke ranks with Hizb ut-Tahrir the same week that his Newham College classmate and ex-party member, Ed Husain, rose to quasi-stardom with the publication of his kiss-and-tell memoir, The Islamist, a stirring defection story of a Muslim extremist who had come clean.

“He had a soft spot for Mahboub,” Nawaz’s cousin Nabi said, referring to Husain by his middle name. “I think Mahboub had shown Maajid a way of attaining the sort of fame and status he desired.”

Nawaz and Husain formed the Quilliam Foundation in November 2007, capitalizing on the British government’s plans to bankroll a new crop of Muslim-led counter-extremism groups that were more pliant than its predecessors. According to Quilliam, the British government shelled out the equivalent of more than $3.8 million to Nawaz’s group between 2008 and 2011. In testimony before the Communities and Local Government Committee of the House of Commons in November 2009, Husain reported that they were in receipt of £850,000—more than a million dollars—per year in state dough, and last year Nawaz drew a salary of more than $140,000.

Before long, the scrappy son of Essex had a book deal, and traded in his prison garb for Harris tweed waistcoats and red corduroy pants—a get up he described as “versatile and smart” in his 2014 Sunday Times “Masters of Fashion” profile. “My day can include being in the Newsnight studio or with friends or at Downing Street, so dressing is tricky,” he said.

“[Maajid and Ed] were in a unique position [and] one that would equate to fame and riches, but rationalized it to themselves that they were fighting a good fight against Islamists,” Hoque said.

Whether a genuine conversion or an opportunistic about-face, it’s impossible to know with certainty what compelled Nawaz to leave Hizb ut-Tahrir and espouse his current agenda. What lies at the heart of tensions between he and so many of his former close acquaintances, though, is clearly a trust deficit. They see him as an Islamic Judas Iscariot, a Muslim who turned his back on his fellow believers when state coffers flung open—and their testimony reflects that sense of betrayal.

“He has been rejected and routinely opposed by many in the community,” his cousin Nabi said. “His support only exists outside of the Muslim community with the neocon/liberal establishment.”

Nawaz has said that his approach is one of dialogue and seeking common ground. That’s music to the ears of many who are turned off by polarized debates about religion and politics. Yet for all the right notes that he hits (public “conversations” with controversial figures, and calls to reject racial profiling) Nawaz’s stated mission is at odds with many of his actions. He’s wheedled Western politicos who advocate draconian policies that target Muslims, and he indulges the worst offenders when it comes to anti-Muslim prejudice.

He’s friendly with hawkish heads of state: David Cameron tapped him as an adviser on combatting

extremism, Tony Blair gushed admiration in a front-cover book

blurb, and George W. Bush picked his brain about torture at a backyard

barbeque in Dallas. Nawaz has also surrounded

himself with a motley crew of illiberal ideologues. Quilliam has received more than a million dollars from a group with close ties to Tea

Party conservatives; Ted Cruz’s campaign chairman, Chad Sweet, who advises a

domestic spying program of the FBI, sat on Quilliam’s board until 2013; former Israeli Vice Prime

Minister Silvan Shalom, who adamantly opposes Palestinian statehood, shared the stage with Nawaz at an event in Toronto last October; and clearinghouses

like the Clarion Project and the Gatestone Institute, which finance anti-Muslim

activists, are habitually chummy with Nawaz and his comrades.

Some of his most vocal supporters, though, include New Atheists that seem to take great pleasure in lambasting Islam. There’s a strong current of affection that flows between Nawaz and Sam Harris, who calls the religion the “mother lode of bad ideas” and has advocated racial profiling and torture (Harris has donated $20,000 to Quilliam). HBO’s Bill Maher, famously hostile toward Islam, wished that there were “a thousand” of Nawaz, while Richard Dawkins (“to hell with their culture”) lauded him as a “truly moral & brave man,” and urged his online flock to support Nawaz’s failed 2015 parliamentary bid. The ex-Islamist has even cozied up to Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali-born activist who once tagged the Muslim faith as a “nihilistic cult of death” that should be “defeated” by any means necessary, including militarily.

That Nawaz enjoys the company of such a galère isn’t the problem. He’s not guilty by association. He’s guilty of giving life to their extreme ideas. In 2009, when his Quilliam associate Ed Husain advocated spying on British Muslims, Nawaz chalked the ensuing controversy up to the bellyaching of a “pro-Islamist brigade.” The next year, he sent the country’s security and terror chief a McCarthy-esque list of Muslim groups that the government should be wary of lest their non-violent views morph into violent ones. Nawaz’s organization, along with a software company, developed “radicalization keywords” used in a computer program that monitored the Internet searches of school kids and flagged would-be extremists for investigation. And Tommy Robinson, the former leader of the far-right, anti-Muslim English Defence League, alleged Quilliam paid him thousands of pounds to resign in a move that many saw as a bribe: Robinson stepped down, and Quilliam took credit for bringing about his departure. The money, Robinson said, went to pay “my wife’s rent and help with basic bills, [and] in return Tommy Robinson would be their poster boy.”

On Twitter, Nawaz has posted controversial caricatures of Muhammad, urged veiled women to take off their hijabs, and questioned the state of mind of Ahmed Mohamed, the 14-year-old “clock boy”—all while trading “solidarity” hashtags with militant secularists and ignoring prejudice that faces his own religious group. Such is Nawaz’s playbook for achieving fame: court controversy by baiting religious believers (usually Muslims) and hitching his wagon to the provocateurs of the secular pundit circuit.

Nawaz has indeed found the spotlight—and it hits him squarely as he stands on the stage of the Andrew Mellon auditorium in Washington, D.C. It’s October 2015, and he’s at the American Abroad Media’s annual dinner to accept an award on behalf of online anti-extremist activists in the Middle East.

“I’m honored, incredibly so, to accept this plaque on behalf of all those profiled in this video, and the many others who are risking their lives fighting against extremism and for a better future for us all,” he says, gazing out at a farrago of ambassadors, journalists, and luminaries.

Later that night, Nawaz tweets a photo taken of him during his acceptance speech and announces he accepted the award on behalf of anti-ISIS group Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently. Puzzled, a member of that group tweets at him, “What is going on guys ?? we didnt go to this event ???”

“You were among those honoured in your absence,” Nawaz replies. “I was asked to receive the award on your behalf.”

“Really no body tell us anything!”

“Now you know. Keep up the great work. Your reputation is spreading. Much deserved!”