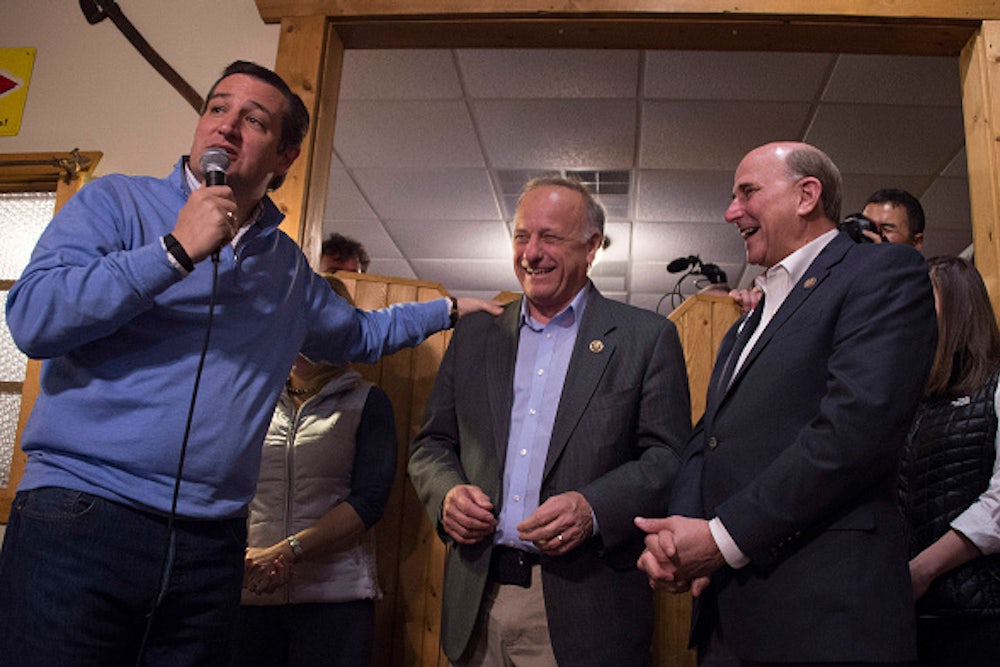

Steve King could not hold back the tears Monday night as Ted Cruz, the Iowa congressman’s annointed presidential candidate, stood at the podium in Des Moines and triumphantly rambled about Jesus, “courageous conservatives,” and the nebulous menace of something called the Washington Cartel. Others—Senator Cruz first among them—may be able to stake more immediate claims to victory on Monday, but no one had a better caucus night than King did.

For King, it was a moment 14 years in the making. That’s not simply because, in the face of waning poll numbers, his grassroots activist network had just helped deliver a record turnout for Cruz, solidifying King’s status as a kingmaker in the ever-important early-voting state. It’s also because the outcome of 2016’s first electoral contest marked the larger conquest of the small-town nativist politics King brought to Washington a decade-and-a-half earlier.

In the aftermath of Iowa, the 2016 Republican primary appears to have become a three-way race between Cruz (a King disciple), Donald Trump (arguably running to the right of both on immigration, King’s signature issue), and Marco Rubio (who King helped cow into opposing his own comprehensive immigration bill back in 2013). Regardless of which candidate goes on to claim the nomination—and even on the off chance that someone else eventually does—he’ll be inheriting a party warped, perhaps irrevocably, by the ideological hard line King has been fighting throughout his political career.

This election has been defined by two trends that, as the New Republic’s Brian Beutler recently explained, have been reinforcing one another for decades. The first is the emergence of white nationalism as the primary animating force of movement conservatism. The second is the utter disintegration of centralized power within the GOP. King certainly can’t take sole credit for either, but in his long, tenacious, often-vicious campaign to impose his nativist agenda on the Republican Party, he’s played a singular role in ensuring the final realization of both.

King entered Congress in 2002, at a time when the Bush White House was still operating under the old Reagan-era canard that Latinos are conservatives who just don’t know it yet. Karl Rove, Bush’s political guru, believed—and still does, for what little that’s worth—that incorporating Hispanics into the GOP was vital to the party’s long-term national prospects.

King had different ideas. A state senator from Iowa’s rural northwest, he had scraped through a tight, four-way primary, largely—as he himself would later acknowledge—on the popularity of an English-only law he had browbeaten through the Republican state house that very year. His district, like so many others across the country, was in the midst of rapid demographic changes. (Between 2001 and 2014, Iowa’s overall Latino population would more than double. Six of the 11 most heavily Latino counties in the state, including the top two, fall in King’s district.) King understood the political utility of the anxieties those changes produce (and so, too, for that matter, did the Republican elites who now wash their hands of his excesses).

In his first term, King was to be a loyal proponent of the Iraq War, even as others in Bush’s party began to distance themselves from its failure. But in 2004, King broke twice with major administration national-security initiatives he deemed to be too soft on immigration. In the second instance, King introduced an amendment to a Justice Department spending bill that would have withheld federal funding from state and local law-enforcement agencies that provide “sanctuary” to undocumented immigrants. The chair of King’s House Subcommittee on Immigration shot the bill down, saying it had no place in a routine appropriations procedure, and King was forced to withdraw it for lack of support.

Since the Tea Party revolution of 2010, King’s tactic—inundating unrelated spending legislation with aggressive, poison-pill items picked straight off the far-right wish list—has become the modus operandi of the Republican House. And King, of course, never stopped talking about “sanctuary cities”—an issue that was injected into the presidential campaign last year after Kathryn Steinle, a white woman, was killed by Juan Francisco Lopez-Sanchez, an undocumented Mexican immigrant.

To say simply that Steve King was a few years ahead of his time, though, is to miss the point. Despite all evidence to the contrary, King is an intelligent political operator. He never thought he would prevail in those early showdowns—in some ways, it was actually better that he didn’t. King’s beliefs, by all accounts, are sincere, but his approach to lawmaking is, like his rhetorical outbursts, performative. He provokes confrontation for its own sake: to sanctify his conviction, to expand the realm of what’s possible. And through the determined, and indeed deliberate, legislative failures of his first few terms in office, King succeeded in creating the conditions for today’s right-wing uprisings—in fostering the toxic resentment and affective rage that has supplanted any legitimate governing impulse in the mindset of congressional Republicans.

Donald Trump was still a registered Democrat back when King first started displaying the instinct for manipulating outrage that has made him the bane—and no doubt click-rate blessing—of so many in the liberal media. In 2006, he published a letter on his official website claiming that, between drunk-driving accidents and cold-blooded murders, 25 citizens a day were killed by undocumented immigrants. The number was a hodgepodge of willfully misleading statistics, but as soon as journalists began pointing out as much, the slander captured imaginations in the right-wing information bubble and was soon “repeated hundreds of times,” according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, “sometimes by extremist activists like Clyde Harkins of the American Constitution Party.” (The buffoonish hyperbole of King’s infamous “calves the size of cantaloupes” riff would be a later and more obviously Trumpish example.)

When Bush-backed comprehensive immigration reform came up in the Senate that year, King held a press conference declaring that anyone in favor of the bill “deserves to be branded with a scarlet letter, ‘A’ for amnesty.” The word “amnesty” was subsequently mentioned more than 50 times in a single day of ensuing debate in the Senate. Eventually, the Bush administration had no choice but to admit the vision of a more inclusive GOP had already been squandered. The next immigration bill the White House introduced focused solely on border security. By now, even the most “moderate” GOP candidates must make “border security first” a prerequisite for even considering overarching reform.

King did not limit himself to feeding inflammatory soundbites into the propaganda machinery of the culture wars. In 2006, he joined forces with Southern conservatives to hold up reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act. This time, 79 other members of Congress signed onto a letter King penned, calling for the removal of provisions guaranteeing access to bilingual voting materials in areas with large Spanish-speaking populations. After several weeks of embarrassing parliamentary discord for the GOP leadership, which had made a show of moving to preemptively renew the landmark legislation, King’s amendment was ultimately defeated. But, again, in that doomed campaign you can detect the budding seeds of today’s nationwide voter-suppression movement, which targets both blacks and Latinos, often interchangeably.

In 2002, King ran for Congress as a small town, English-only crusader, vowing to “move the political center towards the right.” Watching him onstage Monday night— weeping tears of joy that the guy who made his bones hunting RINOs on the floor of the Senate had beaten the guy who wants to make Mexico pay for a border wall—how could anyone say he hasn’t?