The most obscure figure in The People vs. O.J. Simpson—both the TV series and the real case—is the man who was, at least in theory, at its very center. The series finale ends with Simpson leaving his palatial home on the night of his acquittal to gaze up at a statue in his yard. The statue depicts him in his days as a football hero—strong, handsome, famous, invincible, loved—and in the show’s final moments, we watch the O.J. Simpson of October 3, 1995 contemplate a man he no longer is, and perhaps never really was.

If the series fails to present a compelling version of the title character, it had other things on its mind: chiefly, the complicated ways that race, fame, wealth, and gender interact with the American legal system. Such themes will inevitably usurp even the characters who inspired them. But if the finale of The People vs. O.J. Simpson leaves you wanting to learn more about its players, you won’t suffer from a lack of reading material. In the aftermath of the verdict, literary agents were all but handing out publishing contracts to anyone exiting the courtroom. (The sole exception, as the finale notes, was Judge Lance Ito.) Johnnie Cochran wrote a book; Robert Shapiro wrote a book; one of the jurors wrote a book; people whose names may have been unfamiliar to even the most diehard followers of the trial—Gerry Spence, Tom Lange, Mike Gilbert, Daniel Petrocelli, and Paula Barbieri—wrote books. And, yes, Kato Kaelin wrote a book. Did you really have to ask?

Mark Fuhrman wrote an account of the case, Murder in Brentwood, and then adopted a second career as something of an avenging angel: His subsequent book, Murder in Greenwich, purported to crack wide open the long-unsolved murder case of Connecticut teenager Martha Moxley. (The book was adapted into a TV movie starring Christopher Meloni of Law & Order: SVU; in it, Fuhrman comes off as exactly the kind of hard-driving, TV-ready cop viewers are used to wanting on their side.) Marcia Clark and Christopher Darden each wrote a book, but perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us that both prosecutors, having experienced such astonishing defeat in the media free-for-all where they represented the “search for truth,” have since turned to fiction: Darden to a set of hard-boiled L.A. novels (The Trials of Nikki Hill, L.A. Justice), and Clark to several character-based mystery series. The main character in her “Rachel Knight” books “is a tenacious, wise-cracking, and fiercely intelligent prosecutor in the city’s most elite division.” In the final moments of 2012’s Guilt by Degrees, Rachel reflects: “If you wait long enough, all your enemies will be vanquished.”

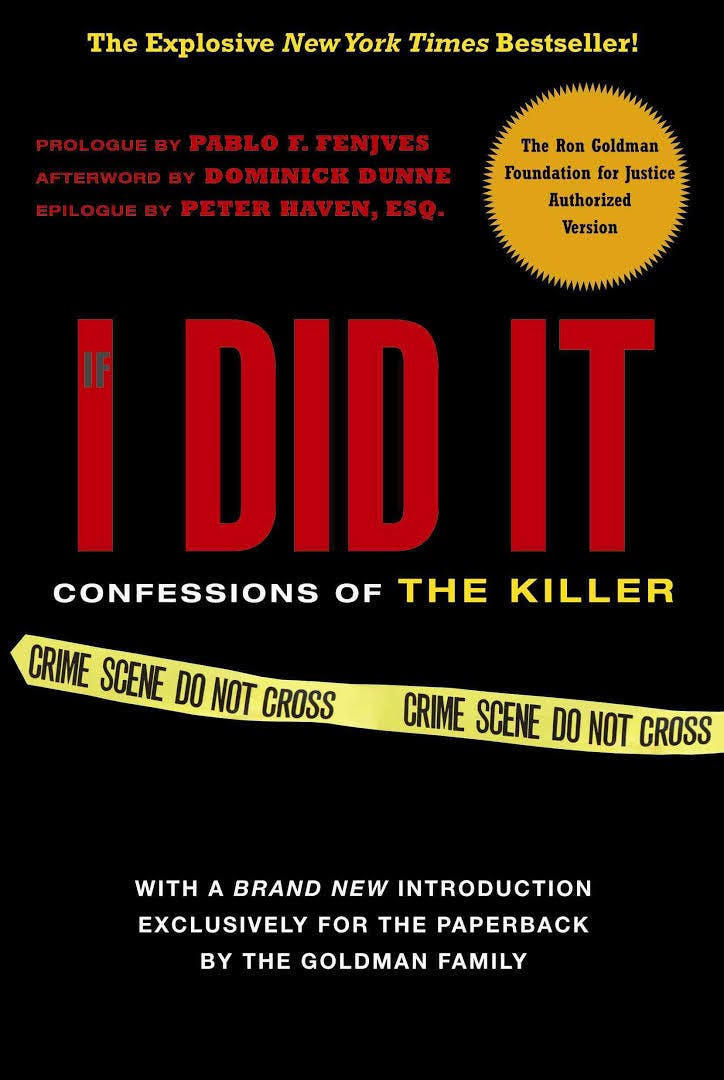

The publishing industry has been kind to all the players in the O.J. Simpson trial, except one: Simpson himself. In 2006, Simpson was scheduled to release a ghostwritten memoir titled If I Did It, but widespread outcry led the book’s original publisher, HarperCollins, to cancel its publication and destroy all remaining copies. (James Wolcott at Vanity Fair managed to snag a pre-pulped copy for review: “Despite its animating anger,” he wrote, “it’s a book that projects a strange lack of affect, a suave void.”) The book reached the public the following year, when the family of Ronald Goldman published it instead, hoping to scrape together some of the compensatory damages a judge had awarded both them and Nicole Brown Simpson’s family in 1997, after they won a civil suit against Simpson for the wrongful deaths of Ron and Nicole.

Twenty years after the murders, the Goldmans said they had still received less than one percent of the $40 million owed them. That’s because O.J. Simpson was broke. He had been worth an estimated $11 million on the day he was arrested, but after his 1997 civil trial, his lawyers claimed he was nearly a million dollars in debt. After his acquittal, Simpson had won back his freedom, but not the goodwill of the community in which he had once been a beloved icon, or of the media that had made his trial a national fixation.

I Want to Tell You: My Response to Your Letters, Your Messages, Your Questions, a 1995 book compiling correspondence Simpson had received while at trial, initially sold well, even though some bookstores refused to advertise it. But plans for a pay-per-view interview special featuring Simpson, which made headlines immediately following his release, were quickly scrapped, and the work Simpson found in sports commentary and TV commercials—his bread and butter since he retired from pro football in 1979—disappeared. What money he did make by the time of the civil trial seemed to come primarily from selling autographs and sports memorabilia. American viewers couldn’t get enough of the Juice until the day they realized their thirst for a story had allowed them to forget what was at stake: two lives lost, two children left motherless, two families destroyed. Suddenly, it was hard not to want it both ways, and to decry the miscarriage of justice that concluded what had been until then, for many viewers, a harmless soap opera.

“The killer” is how

O.J. Simpson is always referred to in the Goldman family’s preface to If

I Did It. Titled “He

Did It,” it opens a book whose cover renders the “if” of the title all but

microscopic. After sitting through nine months of a trial in which Simpson was

referred to as everything but

“the killer,”

it seems the chance to refer to him this way might have been incentive enough

for the Goldman family to publish the entire book. To the family members who

survived and mourned their son and brother, speaking this phrase aloud must

have been like saying “hallelujah” after Lent.

In this revised form, If I Did It is a strangely illuminating text. The Goldmans framed the book in a way that makes O.J. Simpson’s guilt unambiguous, which certainly isn’t difficult; even the portions that Simpson had signed off on didn’t leave much room for doubt. In a chapter titled “The Night in Question,” Simpson—or at least Simpson’s ghostwriter—describes Simpson arriving at Nicole’s house, and encountering Ron Goldman at the gate. “She’s got candles burning inside,” Simpson rages. “Fucking music playing. Probably a nice bottle of red wine breathing on the counter, waiting for you.”

“Not for me,” Goldman protested.

“Fuck you, man! You think I’m fucking stupid or something?”

Suddenly the front door opened. Nicole came outside, alerted by our raised voices. She was wearing a slinky little cocktail dress, black, with probably not much on underneath… Nicole came at me, swinging. “Get the fuck out of here!” she said. “This is my house and I can do what I want!” … She came at me like a banshee, all arms and legs, flailing…

As Simpson tells it, Nicole falls and hits her head, Ronald Goldman strikes a martial arts pose, and Simpson feels the knife in his hand. And then, he says, “Something went horribly wrong, and I know what happened, but I can’t tell you exactly how.” Like the American public, O.J. Simpson wanted to have it both ways: to profit from the murders while still claiming his innocence.

In the case of

the People vs. O.J. Simpson, there are no innocent parties. There are also no

winners. As the Goldman family was promoting If I Did It in the fall of

2007, news broke that O.J. Simpson had been arrested in Las Vegas for

robbery and kidnapping. He had attempted to steal, from a dealer’s hotel room, sports memorabilia that the

claimed had previously been stolen from him. At first, he seemed happy to

ignore the charges: “I’m not

walking around feeling sad or anything,” he told The Los Angeles Times, “I’ve done nothing wrong.” But on

October 3, 2008—exactly 13 years after he was acquitted of the murders of

Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman—Simpson was sentenced to between nine

and 33 years in prison, an astoundingly high sentence for the crimes

of which he was convicted. He will be eligible for parole next year, by which

time he will be seventy years old.

“I don’t like to use the word payback,” his lawyer, Yale Galanter, has said of the sentence. But, he adds, “I can tell you from the beginning my biggest concern was whether or not the jury would be able to separate their very strong feelings about Mr. Simpson and judge him fairly and honestly.” If we are to see O.J. Simpson’s trials as object lessons in American law, we have to wonder how Simpson would have fared if he had still been able to afford the lawyers who defended him 20 years ago.