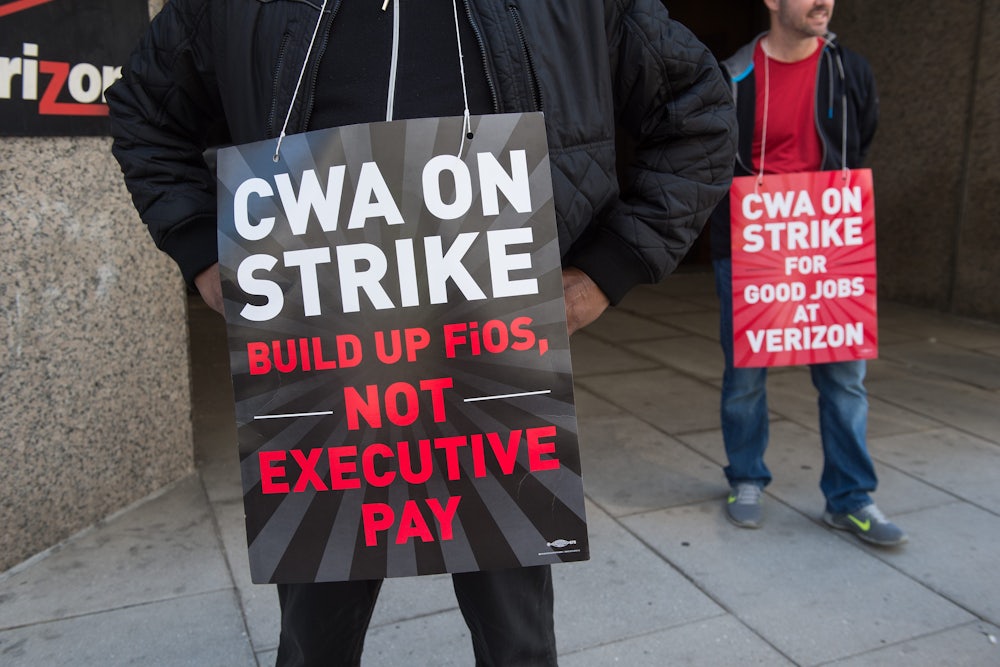

When you push workers hard enough, eventually they’re going to push back. That’s what we’ve seen this week, as Verizon workers initiated the largest strike in America in several years—actually since the last Verizon strike in 2011. Thirty-six thousand landline phone and broadband employees walked out on Wednesday after contract negotiations broke down.

The Verizon case incorporates big themes in the economy—outsourcing, monopolies, automation, and inequality, to name a few. It reflects the gradual thinning out of good-paying, middle-class U.S. jobs. And in this election year, it forces politicians to choose—not just between labor and management, but between a future of shared prosperity for workers and one in which a lot of low-paid service employees cater to the bidding of the ultra-rich.

The last Verizon strike lasted only two weeks and ended without a new contract, but simply the resumption of negotiations. A year later, the two sides signed a three-year contract, which ran out last August. After months without a resolution, Verizon workers affiliated with the Communication Workers of America decided to strike again.

One big difference is that 43,000 workers struck in 2011, compared to 36,000 today. According to CWA, that’s because 5,000 call-center and customer service jobs have been outsourced to low-wage, non-union contractors operating in Mexico, the Philippines, and the Dominican Republic. Those contractors cost Verizon a fraction of the $35- to $40-per-hour average wage for its U.S. workers, and with no health or retirement benefits. Verizon has automated some of its customer service as well to save money.

In contract negotiations, Verizon asked to consolidate more call centers and route more calls overseas to facilitate outsourcing. The company also wants to redeploy existing technicians away from their homes for months at a time to service its network, which CWA sees as a deliberate effort to force workers to quit.

Verizon deems this all necessary because its landline business is hemorrhaging customers, as people cut the cords on their home phones. Verizon lost 1.4 million landline subscribers just last year. But the super-fast FiOS broadband network, also considered part of the wireline business, is booming, with sales up 9 percent last year. While total gross revenue was down 1.8 percent in 2015, the overall business made $8.9 billion. Only $300 million in savings came from reducing employee costs, according to Verizon’s own figures. In other words, the wireline business remains very profitable.

And Verizon’s wireless business, staffed mostly with non-union employees, is doing spectacularly, with obscenely high profit margins—nearly 40 cents on every dollar of revenue. The company could use that money to invest in high-demand services like FiOS, but except for one announcement this week of an expansion into Boston, FiOS build-out has stalled.

In sum, Verizon seems to be over-emphasizing the part of its business with non-union workers and under-emphasizing the part with a unionized labor force. Indeed, Verizon is using the rhetoric of technological change to shortchange its union workers. “Nostalgia for the rotary phone era won’t save American jobs,” wrote Verizon CEO Lowell McAdam in a much-discussed LinkedIn post. But he also acknowledges within that post that wireline has transformed into a broadband company that still can produce good-paying jobs.

Verizon’s challenges haven’t caused Lowell McAdam or his executives to reduce their salaries, of course. He made $18.3 million in 2014, a 16 percent increase from the previous year. In fact, all the top executives have seen a surge in their earnings. Most of McAdam’s compensation, $12 million, came in stock, which gives him a tremendous incentive to keep the stock price high regardless of whether workers—or even customers—suffer. That means reducing labor costs and squeezing out profits.

The shift to a foreign workforce has degraded the quality of the Verizon product—ask anyone who’s ever been on the phone for customer service with them. Verizon continues to outsource because, as one of just a handful of major telecoms, they don’t really have to worry about market share. In my area, Verizon was the only available seller of DSL broadband, competing only with more expensive cable service from Time Warner, until it divested from California wireline service this year, selling it to Frontier Communications. There’s simply no value in keeping quality high because customers are cornered, with nowhere else to go.

This strike could linger beyond the two-week walkout in 2011. Verizon has planned for thousands of non-union workers to cover for the striking employees, unlike the handful of managers they used five years ago. But the strike really signals a larger economic fight—between workers immiserated in large and small ways for decades, and large corporations with monopoly-like power who want to use societal, political, and technological change to acquire a greater share of the total revenue produced at their companies.

Both Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton joined picket lines and pronounced their support for the striking workers on Wednesday. After McAdam’s LinkedIn post, which was largely a broadside against Sanders for his “contemptible” rhetoric, Sanders responded by tweeting, “I don’t want the support of McAdam … and friends in the billionaire class. I welcome their contempt.”

Solidarity is no doubt important, but workers need more opportunities to fight back. The Verizon strike isn’t a sign of anything so much as desperation, as Verizon plays its large non-union workforce against their union brothers and sisters. In fact, corporations’ ability to raise their leverage against workers goes hand-in-hand with the decline of the labor movement. It helps explain why wages have stagnated while corporate profits and executive salaries rise.

Breaking the power of monopolistic corporations that harm consumers with higher prices and lower quality while harming workers with lower wages and benefits can help solve this inequality puzzle, and we are seeing pressure from Congress to make antitrust agencies more effective. Preventing trade deals, even in services like telecommunications, that allow jobs to move overseas can also help. But the main issue is that workers lose when they cannot band together. Technological change alone is not stirring these anxieties. It’s that most peoples’ wallets get lighter while a few others get fatter. Collective action can solve that power imbalance; that’s what we’re seeing at Verizon. But only 11 percent of the workforce is unionized.

Last year, Bernie Sanders introduced the Workplace Democracy Act, which would let workers unionize if a majority of employees sign cards expressing that preference. Hillary Clinton has vowed to resurrect the so-called “card check” bill as well. But even a majority Democratic Congress couldn’t advance this bill in 2009; there’s little hope of its passage under Republican legislative control.

That’s why we’re likely to see more strikes. They won’t only come from unionized labor—yesterday we saw the largest-yet walkout among Fight for $15 fast food industry workers as well. Those without a union are just as frustrated as Verizon’s CWA members with an economy where more and more income flows to the very top. We can reverse that trend, or we can have more people in the streets.