When Herbert Croly died in 1930, the magazine was left without its ideological father. Even though his leadership style contained not a trace of charisma, he had meticulously maintained a liberal editorial line. He had permitted sympathy for radicals and published them, but the official editorial position never came too close to socialism. Yet with his passing, his young protégés began insisting on a harder leftism.

Edmund Wilson didn’t have the temperament of a party hack. But the trauma of the Great Depression had launched him toward the Communist Party, where he dabbled on the margins. He wanted “to take Communism away from the Communists,” as he wrote in the magazine in 1931, and to apply the party’s best teachings to American politics. The spirit of the party with its adoration of the common man also inspired him to step down as the magazine’s literary editor. (The Daily Worker was keen to hire him; he hesitatingly resisted.) Wilson asked for a pay cut so that he could travel the country reporting on the ravages of economic collapse. Despite Wilson’s befouled politics, these pieces stand the test of time. He managed to capture American life from almost every angle: He interviewed autoworkers, traveled across the South with a Red Cross worker, and wrote about fancy hotels. The title of this piece is also the title of Henry George’s nineteenth-century tract, one of the greatest works of American radicalism.

—Franklin Foer, former TNR editor, Insurrections of the Mind: 100 Years of Politics and Culture in America

There is no question that the Empire State Building is New York’s handsomest skyscraper. The first five stories, with their gray facade, silver-framed windows and long rainlike lines in the stone, rise graceful and sheer from the street: one feels a sudden relief as one passes them—they do not crowd and overpower Fifth Avenue as most of the newer Fifth Avenue buildings do. And the successive tiers fall back, each just in time not to make too heavy and dull a wall—till the main towering plinth is reached. Close to, the long lines of the nickel facings have the look of a silver inlay and the whole long pale and silver strip might be an inlay on the pale even blue of the sky. This towering plinth, though it is the tallest in the city, has almost always an effect of lightness. From far off the gray observation tower looks as light as if it were made of shadows, its silver cap as it catches the sun, as bright and brittle as a Christmas-tree globe. In a warm afternoon sun the building is bisque-pink, with delicate nickel lines: a rainy day makes a pleasant harmony with bright pale facings on dull pale gray; on a chilly late afternoon, the mast is like a bright piece of silverware, an old salt-cellar elegantly chased. And though in a rawer light the building looks less fine, it may still seem as insubstantial as a packet of straw-colored Nabiscos stuck together and stood on end. In the cold dazing light of a winter morning, a bluish-gray block with gleaming silvery edges against a grayish-blue sky. It seems semi-translucent like a cake of ice. Only rarely in glaring midday does it look metallic, functional and hard like a machine-part.

The Empire State Building is the tallest building in the world: it is 1,250 feet high.* There is a telescope in Madison Square Park for people to look at the tower through, just as they used to look at the moon. There are 86 stories, not counting the mast; 6,400 windows; and 67 elevators. The building contains 10,000,000 bricks and weighs 600,000,000 pounds—distributed, however, so evenly that “the weight on any given square inch is no greater than that normally borne by a French heel.” The plot on which it stands is only about 200 by 425 feet, but the building contains 37,000,000 cubic feet. It is calculated that, if it were full, there would be 25,000 people working there and 40,000 more people going in and out every day. In the immediate future, however, there will not be by any means that many, because business is extremely bad and even the office buildings already erected are full of untenanted space. Of the offices in the Empire State Building only a quarter have so far been rented, and in moving into it, most of the tenants will merely be leaving further vacancies elsewhere. The Empire State Building was put up at top speed in less than a year: in one case, telephoto had to be employed to get the right materials rushed from Cleveland. And now here it is planted in the business district where nobody needs it at all and where it is sure to make a good deal worse one of the worst traffic-jams in town.

The people responsible for the Empire State building, who contributed more than half the $52,000,000 required for it, are John J. Raskob of the Democratic National Committee, Pierre du Pont of the Du Pont Powder Company, and the presidents of the Nipissing Mines Company and the Chatham Phenix National Bank and Trust Company. Al Smith is the president of the owning company and is said to get $50,000 a year. Today, the first of May, the day of the formal opening, he looks very compact, decent and well satisfied, in his dark coat and black derby, with his official family around him. It is his two little grandchildren who perform the ceremony of opening the building by cutting a ribbon across the Fifth Avenue entrance. Then the lights are switched on by an electric button pressed by President Hoover in Washington. Then there are speeches on the eighty-sixth floor. Al Smith reads a telegram from President Hoover, which congratulates “everyone who had any part in its conception and construction” on “one of the outstanding glories of a great city.” Governor Roosevelt congratulates them on their “grasp of the needs of the future”—he asserts that the Empire State Building “is needed not only by the city, it is needed by the whole nation.” There are two keynotes today, he says: one is the keynote of vision, the other is the keynote of faith. Mayor Walker, whose administration is under calamitous inquiry and whose impeachment has recently been demanded, congratulates them on having provided “a place higher, further removed than any in the world, where some public official might like to come and hide.” Then the R.K.O. “Theatre of the Air” broadcasts a radio program.

The entrance hall of the Empire State Building is four stories high and made of gray German marble with an effect of crushed strawberries rubbed into it. On the far illuminated cream of the long ceiling are gold and silver circles, stars and suns, conventionalized geometrical patterns supposed to be derived from snowflake crystals. At the end of the hallway is an enormous flat steely sun blazing on the flat steely Empire State Building with a bombardment of rays like railroad tracks. The elevator doors are black with silver lines and have a suggestion of Egyptian tombs. There are a great many uniformed guards, with guns in holsters, posted around.

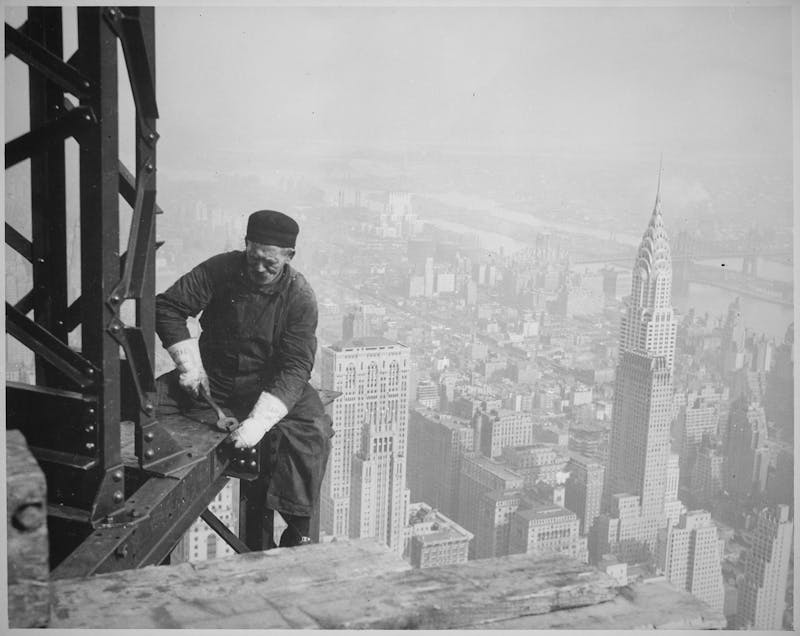

The fifty-fifth floor is the show floor. Green marble and green doors: a great empty loft with bright white walls with black ends of wire sticking out of them and crumbs of plaster on the floor. Through the unwashed windows streaked with dirt the windowed square-walled wilderness of buildings has the same dreary yellow as the streaks. If one looks out of an open window, one can see the water-tanks on top of other buildings, somebody’s expensive penthouse done in green and very luxurious with steamer-chairs, an ad which says “Buy Your Furs from Fox” printed in big letters on the roof of a building and aimed at the occupants of the Empire State, and an American flag. Below that, if one leans out, one sees the streets with the pedestrians and the motor cars very small moving straight and slow along them. To the west, the steamboats and barges moving slowly along the Hudson; to the south, the narrowing wedge of the island studded and pronged at the lower end with its own planting of enormous buildings; to the east, the iron blue-gray East River, strung across with black skeleton bridges, a gray airplane above it; to the north, the dwindled Chrysler tower, a tinny; scaled armadillo-tail ending in a stiff stinglike drill, the white vertically-grooved flat-headed Daily News Building, the chocolate and gilded Luna Park summits of the American Radiator Company Building, like a large “castle” out of a goldfish bowl. Here the light of the setting sun strikes that crowded mass of upright rectangles and blunt truncated towers, bringing out in the raw stone and drab brick their yellows without delicacy or brightness, their browns without richness or warmth. Brooklyn, Long Island City, Bronx, Englewood, Hoboken, Jersey City: straight streets, square walls, crowded bulks, regular rectangular windows—more than ten million people sucked into that vast ever-expanding barracks, with scarcely a garden, scarcely a park, scarcely an open square, whose distances in all directions are blotted out in a pale slate-gray. And here is the pile of stone, brick, nickel and steel, the shell of offices, shafts, windows and steps, that outmultiplies and outstacks them all—that, more purposeless and superfluous than any, is being advertised as a triumph in the hour when the planless competitive society, the dehumanized urban community, of which it represents the culmination, is bankrupt.

This big loft is absolutely empty, there is nothing to look at in it—or rather there is only one thing: a crude but genial mural drawn in pencil by, presumably, one of the plasterers or electricians, which, all unknown to the management, confronts every visitor to the fifty-fifth floor. A large male figure is seen standing upright and fornicating, Venus aversa, with a stooping female figure, who has no arms but pendulous breasts. The man is saying, “O, man!” Further along is a gigantic vagina with its name in four large letters written under it.

One is grateful to the man who drew these pictures: he is a public benefactor. He has done something to take the curse off the opening of the Empire State Building.

*The complete facts about the Empire State Building, as well as a scries of drawings of it in course of construction, may be found in Empire State: A Pictorial Record of Its Construction, by Col. W. A. Starrett and Vernon Howe Bailey. New York: William Edwin Rudge. $15,