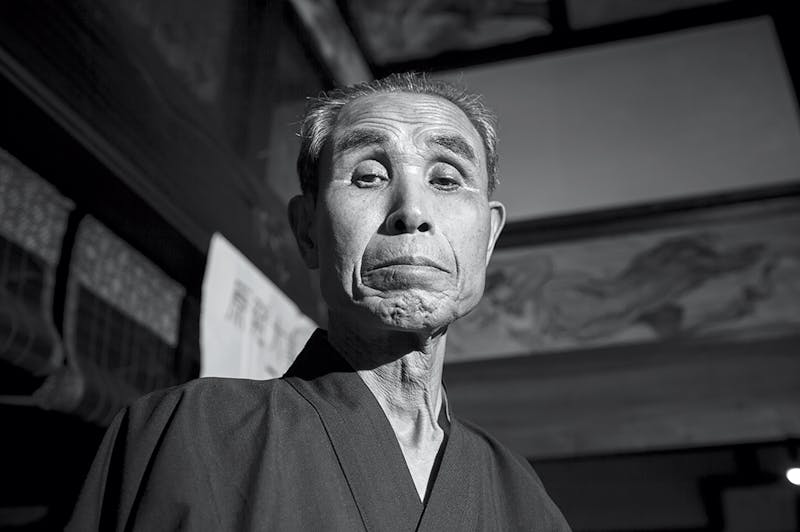

Hisao Yanai, a one-armed, chain-smoking, retired yakuza boss, stands alone behind the bar at Ippei, the restaurant he owns in the Japanese town of Naraha. There are no customers today. The streets outside the restaurant are deserted. Five years ago, on March 11, 2011, a powerful earthquake and tsunami triggered a triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, located ten miles north of Naraha, forcing the evacuation of roughly 160,000 people. Half of them still cannot go home. Last fall, Naraha became the first town in Fukushima’s mandatory evacuation zone to reopen fully, allowing all 7,400 residents to return. Nothing like it had ever been attempted before. Could a town despoiled by radiation be summoned back to life?

When I visit Naraha in the fall of 2015, not long after it reopens, only 150 residents have returned. (The number has since risen to 500.) Most are elderly. The town seems abandoned, like a seaside resort in the off-season. With no functioning banks, schools, or even a post office, Naraha has reverted to the rural backwater that Yanai escaped 50 years ago as a high school dropout. At 15, he ran off to Tokyo and learned to drive a dump truck during the construction boom leading up to the 1964 Olympics. At 16, he lost his left arm to a conveyor belt at a quarry. Eventually, he returned to Naraha and went to work at Fukushima Daiichi, which was flooding the area with high-paying jobs and government subsidies. Naraha, once known in Japan as “the Tibet of Fukushima,” had suddenly been thrust into the nuclear age.

“The nuclear plant changed the history of this town,” Yanai says. “They told us it was 100 percent safe.”

Naraha still has the outward appearance of a sleepy farming community, with tidy neighborhoods separated by rice paddies, fruit orchards, and two rivers tumbling to the sea from the nearby Abukuma Mountains. Since decontamination began about 18 months after the disaster, thousands of workers equipped with little more than garden tools have cut down trees, power-washed streets, and peeled off a two-inch layer of radioactive soil in a 65-foot perimeter around every structure in town. Vast fields and mountainsides have been left largely untouched, save for large burial mounds of black plastic bags filled with low-level radioactive waste that metastasized across the landscape as the work progressed.

There’s no blueprint for remediating a radioactive town and then moving people back into it. After the 1986 nuclear disaster in Chernobyl, the Soviet Union simply abandoned scores of towns. But in a country as densely populated as Japan, abandoning an area the size of Connecticut wasn’t an option. In a concerted push to resettle all but the most severely contaminated areas, the government has spent $31 billion on the cleanup effort, and a staggering $58 billion in compensation payments to evacuees.

The government maintains that it is safe for residents to return to Naraha. Radiation levels in the central part of town average less than 1 millisievert per year—the maximum allowable exposure for ordinary citizens under guidelines set by the International Commission on Radiological Protection. An annual dose of 1 millisievert would increase a resident’s risk for cancer by .005 percent. For a smoker like Yanai, cigarettes pose a far greater threat than radioactive fallout.

Like many residents, however, Yanai distrusts the government. Surveys indicate that half of all evacuees don’t plan to return home. The cleanup effort is widely viewed as political theater, designed to whitewash Fukushima in time for the 2020 Olympics. Encouraging evacuees to return home now would also put an early stop to some compensation payments, which aren’t set to expire until 2018. The government, in short, has a financial incentive to strong-arm mayors into reopening towns before they’re ready, or even properly decontaminated.

“The central government pressured us to lift the evacuation order,” Yanai says. “Nobody in town wanted it, because nothing is prepared.” His restaurant remains the only place in Naraha where you can get a beer. In the two weeks I spent in town, I saw only two people dining at Ippei. Behind the bar, the hands on the clock are frozen at 2:47, the moment when the earthquake hit. Yanai has vowed not to reset it until life in Naraha returns to normal.

One day, Yanai invites me to his home, to see the results of the government’s decontamination program. His house sits on a hilltop, ringed by a concrete wall. When I arrive, Yanai is sitting at a picnic table, smoking. Thick weeds mark the border of the decontaminated buffer zone around his house. Before it was decontaminated, radiation levels in Yanai’s yard measured 10 microsieverts per hour—nearly 50 times higher than the government’s allowable limit.

“There are still places in town that measure 10 micro-sieverts,” Yanai says. He walks over to the corner of his garage, which houses a dusty Mercedes resting on flat tires, and points to a patch of gravel beneath a downspout. This particular spot, he says, was decontaminated three times, because rain kept washing radioactive particles off the garage roof. Government contractors excavated the hot spot each time, but only after Yanai filed a request through the town office.

“If you don’t ask,” Yanai shrugs, “they won’t do it.”

The government has strict decontamination guidelines, but in the field practices are often improvised. At Yanai’s house, contractors dumped wheelbarrow-loads of contaminated dirt in a corner of his garden.

“Look, I’m a nice guy,” says Yanai, grinning. He crushes a cigarette butt into the gravel with his heel. “I said, ‘Fine, if you want to dump it there, I’m not going to say anything. But if you do the same thing in the neighbor’s yard, they might shoot you.’ ”

Yanai is keen to show me his menagerie. His prized specimen is Boo, a boar named for the sound, in Japanese, that a pig makes. After the Fukushima disaster, wild boars came down from the mountains and roamed the evacuation zone, tearing up gardens and ransacking houses. They can still be seen in Naraha, trotting along the road at night. Boo is the size of a small, snaggle-toothed dog. He snorts and gnaws at Yanai’s shin. “They’re not very friendly to people,” says Yanai, shooing the pig away with his foot. “But I’m determined to make him my pet.”

Although Yanai professes to be retired from the Japanese Mafia, his years as a yakuza boss have left him with wealth, influence, and a fearsome reputation. It was rumored that he’d served time in prison for assault. After the nuclear disaster, he used his mojo to force the big construction companies in charge of the cleanup to hire local firms as subcontractors. “In a way,” he says, “the disaster was a good thing.”

Stepping onto the patio in back of his house, Yanai reaches into a galvanized steel tub full of water and pulls out a goldfish as big as a grapefruit. There is a technique to feeding them, he observes. “Do it too quick and they die.”

It’s obvious that Yanai misses being a yakuza boss. He is still bending creatures to his will, only now it’s a quirky hobby. He has a wife and daughter, but they live in Tokyo.

“It must get lonely here,” I venture.

“That’s true,” says Yanai, releasing the goldfish back into the tub. He watches the fish rejoin its companions. “When I get home they’re waiting for me. They don’t complain if they’re hungry, but they’ll die if I don’t take care of them.”

At the ceremony to mark Naraha’s reopening, Mayor Yukiei Matsumoto performed the banal civic rituals required of mayors everywhere. He planted a tree using a gold shovel, celebrated with a group of children, and projected confidence while posing next to a brightly colored illustration of Naraha’s future. “The clock that was stopped,” he declared, “has now begun to tick.”

A few weeks later, I meet Matsumoto at the town hall. Scattered among the office’s sober furnishings are stuffed toys portraying Naraha’s mascot, an anthropomorphic yellow citrus fruit named Yuzutaro. Between sips of green tea, Matsumoto speaks in a soft monotone. To hear him tell it, running a radioactive ghost town for more than three years was marginally more eventful than a meeting of the zoning commission. He attended countless meetings with government officials and oversaw infrastructure repairs. When he speaks of the town, the word “radiation” rarely crosses his lips. Instead, he prefers vague euphemisms like “environment.”

I ask him to describe what evacuees are most concerned about. At first, he says, they were “quite angry” about “the environmental conditions of the town.”

“And now?” I ask.

“Now there are no problems,” he says, “and people have become tranquil.”

Later, as I talk to more residents, it becomes clear that this characterization is a vast overstatement. It’s obvious to even the most casual observer that only old people are returning to Naraha. If young people are afraid to raise children here, I ask Matsumoto, what kind of future is there for Naraha?

“Naturally we want everybody to come back,” he says. “Elderly people are coming back first.” He places his teacup on the table. “But if the children do not come back here, the town cannot exist.”

For a moment, Matsumoto seems surprised by his own candor. Then he hastens to obfuscate it. Leaning forward in his chair, he redefines Naraha’s existential dilemma as a simple misunderstanding. Naraha is completely safe, he asserts. Parents with young children just need a little more convincing to return. One thing his office could do, he suggests, is to “make the environment around the schools better. Also we need to do something to make the parents understand.”

“Understand … what?”

“Regarding the issue of—radiation,” says Matsumoto, searching for a more diplomatic word. “People have their own ideas about what’s safe. But actually, in Naraha, it’s lower than 1 millisievert per year, which is what the government set for exposure to the public. That’s the reality I want people to understand.”

I ask him if he is happy with the government’s decontamination efforts. Matsumoto chuckles. “Let me say I’m not 100 percent satisfied,” he says. For further details, he refers me to Hiroyuki Igari, the town’s director of radiation measurement.

A week later I speak to Igari, a churlish man with a dosimeter badge—a device that measures a person’s cumulative radiation exposure—hanging on a lanyard around his neck. If anything, he insists, the government is actually overstating the amount of radiation that residents are being exposed to. “I live in Naraha,” he says. “I commute to work. Sometimes I stop by the store. Then I go home. That’s my routine.” He yanks on the dosimeter. “After two weeks, it’s obvious from this dosimeter that my exposure won’t exceed 1 millisievert per year.”

While Igari doesn’t put any stock in the notion that the government is pressuring towns like Naraha to reopen prematurely, he acknowledges that the cleanup is imperfect. In his view, the government has done a poor job of educating people about radiation, and its standards for mopping up recurring hot spots like the one in Yanai’s yard are nonexistent. But he believes that radiation isn’t a determining factor in whether people choose to return.

“People who were stressed in the temporary houses, they just want to come home. They don’t care about dose rates,” Igari says. “People who don’t return are used to their new lives. They’re used to living under one roof. But now they’re split up, and they don’t want to leave their families again.”

But dosimeter readings and official reassurances have done nothing to alter a more fundamental reality: In post-Fukushima Japan, nuclear safety is a bankrupt concept. Officials like Mayor Matsumoto who use the word “safe” in an absolute sense echo the corporate propaganda of companies like Tokyo Electric Power Company, the disgraced utility that owns Fukushima Daiichi. As the son of a TEPCO salaryman, Matsumoto has spent his career working the levers of a political machine that is oiled with money from the nuclear industry. Yet in the aftermath of one of the world’s worst nuclear disasters, he still believes himself to be a credible authority on the relative safety of low-dose radiation.

The truth is that there’s no such thing as a “safe” dose of radiation, only gradations of risk. Epidemiological studies show that cancer risk increases in tandem with radiation dose, but we know very little about the risks associated with doses below 100 millisieverts per year. Denying that risk contradicts most people’s inherent understanding of safety as a cost-benefit equation. A patient who agrees to a CAT scan of their head, for example, knows that the diagnostic benefit outweighs any increased risk for brain cancer.

Matsumoto prefers to focus on the benefit side of the equation, which doesn’t require him to invent new euphemisms for “radiation.” He points to the brand new secondary school that will open next year, as well as a $50 million retrofit of J-Village, a national soccer training facility presently serving as a staging ground for 7,000 nuclear workers, which will open in time for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

“It’s going to be big news,” says Matsumoto.

There are also plans for a new hotel, office building, and a “compact town” that will house a supermarket, pharmacy, home center, and medical clinic. A robotics research facility is due to open this summer. And thanks to government subsidies, ten companies, including a battery-maker, a pharmaceutical firm, and a steel manufacturer, are thinking of moving to Naraha.

For its investment in Naraha, Tokyo got a showpiece to justify the trillions of yen it’s pouring into Fukushima. Since the disaster, only two of Japan’s 42 operable nuclear reactors have reopened over public protests, and the nuclear industry is desperate for a public relations coup. As we part, Matsumoto repeats the promise he made personally to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. “I told the prime minister that we’re not going to simply reconstruct the town—we’re going to be a model town of the reconstruction,” Matsumoto says, beaming with conviction. “We’re going to do that, and you’re going to see it.”

Convoys of construction vehicles rumble continuously down Route 6, the coastal highway that runs through Naraha and connects the boomtown of Iwaki to the ghost towns of the restricted zone clustered around the nuclear plant. Built for the 1964 Olympics, Route 6 was instrumental in nudging the region out of rural isolation and onto the planning maps of authorities in charge of Japan’s nascent nuclear energy program. Within a decade, Naraha and its neighbors became charter members of Japan’s “nuclear village,” a network of company towns that received government subsidies in return for hosting nuclear power plants.

Tokuo Hayakawa was a young man in 1967 when TEPCO began building Fukushima Daiichi. He is the chief monk at Naraha’s 600-year-old Hyokoji temple, and an ardent antinuclear activist. I visit Hayakawa on two occasions, and each time he wears a white NO NUCLEAR PLANT button pinned to his lapel.

“Since TEPCO started operating here, nobody believed what they were saying about safety,” Hayakawa says. And yet the utility was able to build not just one, but two nuclear plants in Fukushima prefecture: Daiichi and Daini. (Daini was also damaged by the tsunami, narrowly averting a meltdown.) How could TEPCO accomplish this, I ask, if nobody thought the plants were safe?

“As a foreigner, it’s really difficult for you to understand,” Hayakawa says after a long pause. “There’s an atmosphere that keeps people from raising their voices. If something is dangerous, they can’t say it’s dangerous. If something isn’t right, they can’t say it’s not right.”

Social unity is a bedrock feature of Japanese culture, especially in rural areas. The inbred politics of the nuclear village exploited this tendency, fusing the emphasis on communal harmony with corporate interests. Questioning the safety of the nuclear plant was akin to disavowing one’s family, friends, and neighbors. For decades, skeptics bit their tongues, government regulators promoted the absolute safety of nuclear power, and TEPCO executives operated with little or no oversight. This conspiracy of complacency led to dangerous practices, such as locating diesel generators at Fukushima Daiichi in areas that were vulnerable to flooding—a factor that contributed directly to the disaster. Last February, three former TEPCO executives were charged with criminal negligence for their role in the nuclear meltdown.

Hayakawa didn’t want to return to Naraha, but he had no choice. “I cannot abandon the temple,” he says. “There are family tombs here.” Besides, he feels too old to start a new life. He had his hopes set on his grandson taking over for him. But the disaster eliminated that possibility. “I am definitely the last one,” he says. “It’s clear that Naraha isn’t a place to live anymore.”

“The monk was opposed to the nuclear plant from the beginning,” says Toshimitsu Wakizawa, a gregarious 67-year-old newspaper deliveryman who seems to know everybody in Naraha. “And everything he said came true.”

When I approach him, Wakizawa is gathering sticks in his front yard. Japanese people don’t generally engage in conversations with strangers, to say nothing of American journalists who walk up to them unannounced. But Wakizawa chats with me as if we’ve been neighbors for years. He points to houses that are going to be demolished because their owners aren’t coming back.

“I thought 30 percent might return,” he says, “But now I think it’ll be 20 percent, or even less.”

Wakizawa doesn’t blame his neighbors for preferring the conveniences of city life in Iwaki, where 80 percent of Naraha’s evacuees went during the disaster, to the preternatural quiet of their hometown. “It’s even worse here than before the nuclear plants were built 40 years ago,” he says. “When I drive up Route 6, I don’t see any life, not even insects. Around 8 o’clock it’s scary, because nobody’s here.”

Wakizawa is preparing to move back to Naraha in a few days to restart his newspaper delivery business. “People want to read the obituaries,” he says. “That’s why they want the local newspapers—to see who died and what the radiation levels are.”

Today there are only 50 houses on Wakizawa’s delivery route, down from 250 before the disaster. “The town is disappearing,” he says. He’s troubled by the sense of alienation he feels in Naraha’s desolate neighborhoods. People live alone, outside the traditional support networks of neighbors and extended families. Somebody could die at home and nobody would even know. When I tell him that such deaths aren’t an unusual occurrence in the United States, he looks aghast. “That never happens here! We always talk to our neighbors!” He shakes his head, as if attempting to dislodge the thought of a world where neighbors are strangers and people die alone.

“It’s all mixed up,” he says. “Everything is so confused.”

I leave Wakizawa and drive to the ocean, hoping to find some trace of the houses swept away by the tsunami. Instead I find a vast radioactive waste dump, half-hidden behind flimsy white panels decorated with pictures of birds and trees. I stand with my back to the sea, looking west over the dump toward the dark-shouldered mountains. The river plain is a ragged checkerboard of fallow rice paddies dotted with mounds of black decontamination bags. It is a sobering sight in a country where every inch of arable land is intensively cultivated. The Japanese expression for it is mottainai, a feeling of sorrow for something wasted.

Naraha’s “business district” consists of a single prefab metal shed tucked in a corner of the town hall parking lot. It contains a diner named Takechan, owned and operated by Miyuki Sato and her husband, who commute an hour to and from Iwaki each day. The original Takechan, now overrun with vermin and mold, was a neighborhood fixture in Naraha for 40 years. The reincarnated version has all the charm of a hospital cafeteria, with white laminate walls and glaring fluorescent lights. It is packed with decontamination workers in gray uniforms bent over steaming bowls of ramen.

After the lunch rush one day, I sit down with Miyuki. A television reporter from Sweden had interviewed her earlier in the week. “What do you think about the radiation?” Miyuki intones in mock seriousness. Then she claps her hand over her mouth to stifle a giggle. “So we finished the interview very quickly.”

The Satos haven’t yet found a place in Naraha to relocate. They are eager to leave Iwaki, though, partly because of the long commute, and partly because the evacuee community there isn’t as tranquil as the mayor has suggested. Residents are bitterly divided over his decision to reopen Naraha, Miyuki explains. She is reluctant to say more, except that she has been criticized for cooking with the town’s contaminated tap water. She shows me a certificate from the water authority taped to the wall, guaranteeing that Takechan’s water meets health standards.

“We just wanted to open Takechan, that’s it,” she sighs. “But some people don’t take it that way.”

The director of the local water authority, Haruo Otsuka, shows me a machine that tests the county’s drinking water every hour for cesium-137, the primary isotope in Fukushima’s fallout. The results are always undetectable. I tell Otsuka about evacuees who have criticized the Satos. “Those people are just looking for a reason not to come back,” he scoffs. “At first they said radiation levels in the rice paddies were too high. Then it was the roads. Now they’re blaming the water.”

Tensions among evacuees, however, continue to run high. Hiroko Yuki’s family runs the Shell gas station around the corner from Takechan. Although the Yukis were the first to reopen after the disaster, they have recently bought a house in Iwaki. They aren’t moving back to Naraha.

“We say it’s a house provided by the government,” Yuki says.

“Why is that?”

“People are jealous,” she shrugs. “We work all day, morning to night, and profit margins are slim in this business. We’re not making big money, but people don’t believe it.”

Such petty resentments seem unrelated to the serious disagreements among evacuees about resettling Naraha that Miyuki Sato had alluded to. I didn’t understand why anyone would begrudge their neighbors the choice to return—or not. The whole dynamic felt very—Japanese.

“Yes, that’s right, it is very Japanese,” replies Yuki, unfazed. She stands with her hands clasped behind her back, chin tilted in the air, looking a bit like a soldier with her buzzed hair and black Shell uniform. “Japanese people—we always care about how we’re perceived by others. That’s even more true here in the countryside.”

In Japanese society, self-interest is inextricably tied to family, work, and community. But the Fukushima disaster has sliced through those ties like an axe coming down on a bundle of rope. Virtually overnight, tens of thousands of people were set adrift. What looks on the surface like frivolous squabbles are expressions of the profound anxiety many people feel about their place in post-Fukushima Japan. The question of returning home has become a kind of loyalty test that nobody can pass, because home no longer exists.

Nobody understands this better than Kiyoshi Watanabe, president of Naraha’s commerce and industry association and a stolid member of the generation that had a duty, as he puts it, “to keep the house and the family tombs.” Watanabe has returned to Naraha to help “create more opportunities over the next three to five years for younger people to come back and find work.” It won’t be easy. Paradoxically, the disaster has liberated young people from traditional obligations that kept families bound to the same area, even the same house, for generations. Naraha has to reinvent itself to attract new blood.

“In the past, even if the first son lives in some other place, he has to come back to take care of his parents if they ask,” Watanabe explains. “But now he has a good excuse not to: radiation. The parents can’t say anything.”

Glimmers of Naraha’s future can be seen in the recent sale of seven residential lots near the Kido River. A few of the lots, which sold out immediately, went to buyers from Tomioka, a town bordering Naraha that is next to be reopened.

“Naraha won’t take the same form in the future,” Watanabe says. “New people will be moving in, and we have to think about making a new community for them.”

The half-life of cesium-137 is 30.17 years. What’s the half-life of a broken social bond?

“After five years, it’ll be hard to repair,” says Fumiko Yokota. “People just get used to things, good or bad.”

A stout septuagenarian with a mischievous cackle, Yokota lives alone in the hills above Route 6. On my last full day in Naraha, we talk in her kitchen as a warm breeze lifts the sheer curtains over a window offering a distant view of the ocean. Yokota is glad to be back in Naraha. Life in Iwaki “was quite depressing,” she says. But she recognizes that the younger generation has grown accustomed to “living the evacuee life,” and for them there is no looking back.

I ask her what’s so great about life in Iwaki.

“There’s more beautiful people in Iwaki, that’s the biggest difference,” says Yokota, laughing herself into a fit of coughing. “Now maybe this is the twisted idea of an old lady, but I think for some young people the disaster was a stroke of luck.”

Naraha was the kind of place young people forsook for the big city if given the chance, just as Hisao Yanai did 50 years ago. The Fukushima disaster was that chance. Yokota pushes herself up from her chair and goes to the window. Just across Route 6, an elderly couple from Tomioka has built a new house. Yokota met the woman in passing and got a good feeling from her. “I’m thinking we could be friends,” she muses. “It’s not going to happen fast, but gradually this is how we’re going to rebuild Naraha. I can only do what I can do, and that’s not always easy at my age.”

“Bring her a pie,” I joke.

Yokota chuckles. “We’re not like Americans. We’re really shy. I’m not sure they’re looking for friends. But everybody needs to talk to their neighbors.”

Squinting against the sunlight, she clears her throat, her voice a hoarse whisper, and says, “I hope we can be friends.”