In the mid-eighteenth century, Scottish philosopher Adam Smith told a story about markets and goods and people, one that has become the dominant narrative about human nature, as well as the structuring principle for our daily interactions. Society is made up of self-interested individuals, he argued, and through markets these individuals make collective life possible. “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner,” Smith says in The Wealth of Nations, “but from their regard to their own interest.”

Katrine Marçal, a Swedish newspaper columnist, tells a different story. Her tale focuses on Adam Smith and his dinner. Smith, the originator of what we now call economics, may have imagined a table set with self-interest-filled plates, but he didn’t cook his own meals, nor did he pay anyone to do it for him. He didn’t go from one devotee’s house to another like an ancient Greek, and he didn’t sit at a patron’s table like a court painter. Instead, he had his mommy do it.

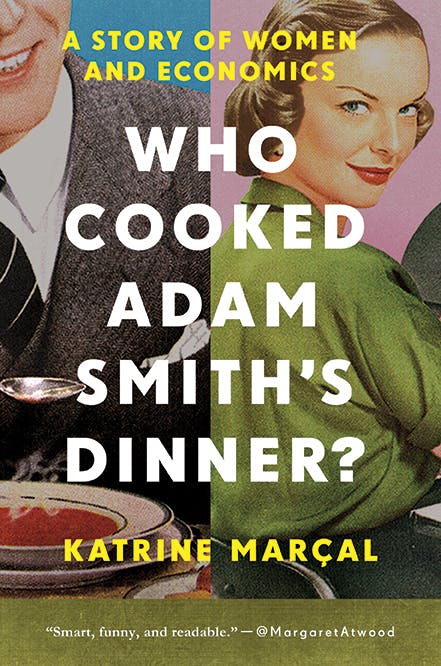

Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? is Marçal’s book-length attack on the idea of economic rationality as a whole, from Smith to the present day. For Marçal, the title story points to a fundamental error in economic ideology: “Somebody has to prepare that steak so Adam Smith can say their labor doesn’t matter.” Much of women’s domestic and reproductive labor quite literally does not factor within economic models. The old joke is that GDP declines when an economist marries his housekeeper, which is not so much a joke as a good explanation of Gross Domestic Product and what it does not account for. The economic rationality that is supposed to guide human behavior isn’t designed to apply to the half of the population expected to work for free. Marçal doesn’t argue that economics is sexist so much as that it’s totally clueless.

Marçal, whose book is now available in English translation, doesn’t soft-pedal her critique. She first published the book in Sweden in 2012, partly as a response to the global financial crisis, and her message is no less valid today. The socioeconomic system may not be hemorrhaging the way it was in 2008, but the wounds don’t seem to be healing.

In trying to express exactly what’s been going wrong, Marçal proceeds by aggressive use of common sense—poking and prodding in plain language at contradictions in economics—rather than in the terms of dense critical theory. She declines to invoke Marxist feminists like Monique Wittig or Selma James (whose work on gender roles seems to have been an inspiration, at least indirectly) or any of their inheritors. If another thinker enters the text, it’s usually to be eviscerated.

The book starts with the 2008 crash. Marçal quotes Christine Lagarde, then French Minister of Finance, who surmised that things would have turned out differently if Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters. That is to say, women might have a better temperament for managing global capitalism. Marçal has little tolerance for this kind of ahistorical thinking:

A world where women dominated Wall Street would have had to be so completely different from the actual world that to describe it wouldn’t tell us anything about the actual world. Thousands of years of history would need to be rewritten in order to lead up to the hypothetical moment that an investment bank named Lehman Sisters could handle its over-exposure to an overheated American housing market.

In short, the thought experiment is meaningless.

Marçal rejects Lagarde and the “Lean In” brand of feminism that imagines women, economically, as heretofore repressed men. The literal translation of the book’s Swedish title, Det enda könet, is “The Only Sex,” which seems to speak to a French feminist tradition that views woman as a product of structural conflict with man. For her part, Marçal makes a radical suggestion that patriarchy, having operated for “thousands of years of history,” is bound to come to an end. It’s not human nature, not biology, just a matter of time. Future societies will look back on economics as a kind of foolish male mysticism, and Marçal’s book anticipates the tone of their laughter.

In short, self-contained chapters, Marçal moves through the contradictions and errors flowing from Smith’s mistake. Although Marçal’s target is economics, her critique applies to social contract theorists and any philosophy that starts with the individual, as in the thought of John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. Only a man, she suggests, would imagine independence rather than dependence as the basis for the human condition. Individualists make the mistake of economic thinking: They forget about their mothers. “No one reads books about childbirth in order to understand human existence,” Marçal writes. “We read Shakespeare. Or one of the great philosophers who write about how people spring from the earth like mushrooms and immediately start drafting social contracts with each other.” To the idea that human society begins with men negotiating for their individual security, Marçal replies, “Hardly.”

Humans, after all, do not crash-land into existence. The uterus is not a spaceship, even if we’re taught to think of it that way. This is how it looks, Marçal points out, in Lennart Nilsson’s groundbreaking photographs of a fetus, which famously appeared on the cover of Life magazine in 1965. In the pictures, a wrinkled baby-to-be floats in a bubble membrane; the background is pitch black, and a cord runs from the baby’s core to… something. This is man before he is born alone into the world, waiting to fall off the tree like a ripe plum. But nothing could be further from the truth: The fetus is entirely enveloped within another human being, and the birth process is called labor.

Once he pulls himself out of the womb by his bootstraps, the imagined economic individual wants one thing: more. “Our most fundamental trait is that we want an unlimited number of things,” Marçal recounts. “Everything. Now. Immediately.” Adam Smith conceded that this was irrational behavior—if we knew what was good for us, we wouldn’t be so willing to trade our time for stuff. But Smith thought humans were fundamentally vain and miscalculating. Later, other market theorists would define rationality according to market behavior, allowing them to understand, for example, altruism as self-interest. Regardless of rationality, the economic individual is understood first and foremost as grabby.

Is that what humans are: Homo Economicus? The story of the economic individual—Robinson Crusoe on his island—might make sense if you forget that women exist, but its implications are still absurd and stultifying. If the capitalist market system is the ultimate expression of the human species-being, then man is an odd bird indeed. Marçal isn’t so sure about the rational justification for an indoor ski slope in Dubai, for example—and that’s just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to capitalism’s ridiculous order of operations. But “if you question economics, you question your inner nature. And then you’re insulting yourself,” Marçal writes. “So you keep quiet.”

Marçal’s book is subtitled “a story of women and economics,” and her critical register is rigorously logical rather than moralizing. She makes an excellent argument for the value of feminism as an analytical lens: It is not a way to show respect or fill out the historical record, but a critical means of differentiating truth from falsehood. Proceeding from the truths that women are people and many people are women reveals the ways in which other modes of thought begin with very different assumptions. By the final page, it’s hard to imagine a good-faith reader maintaining full confidence in the science of economics.

Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? is a masterpiece of rhetoric, clearheaded analysis, and critical imagination. But there’s this move that Marçal makes at the end of the book that’s as familiar as it is frustrating. After issuing a logical argument for a total break with thousands of years of patriarchy, Marçal hits a fork: What is to be done? She writes, “We don’t need to call it a revolution, rather it could be termed an improvement.” I read this to mean, “No one necessarily has to fight about it.” Political books without a concluding commitment to steady nonviolent progress are usually niche products at best.

Not until the conclusion is it apparent how absent violence is from Marçal’s story. Reading the book, you might think capitalist patriarchy is propped up by reason. Marçal is fully convincing when she argues that centuries of individualist thinkers have worked from a limited understanding of human beings. But isn’t that ultimately a little beside the point? Adam Smith didn’t invent capitalism, he just gave it an astrology.

Between Marçal’s ultimate proposal for “improvement” and her characterization of society as an ongoing war on women, the poor, and nonwhite people around the world, it’s the latter that’s better argued. Except for some scandalous anatomical terms, Adam Smith’s Dinner is decidedly PG-13, but gender relations under capitalism aren’t; violence against women is part of the economy. The ongoing war Marçal alludes to a few times is literal, and she never suggests otherwise.

Marçal’s work is a model of radical thought. We have been taught, she writes, to identify with economic man: with “the depth of his feelings,” with his “fear of vulnerability, of nature, of emotion, of dependency, of the cyclical, and of everything we can’t understand.” Of course, the particular lies that patriarchy has put to use over the last few millennia have been dispelled and recomposed time and time again, but Marçal’s critique—and the anti-capitalist feminist tradition on which it stands—is a historical insight of unimaginable potential. “We could go from trying to own the world,” she writes, “to trying to feel at home in it.”

Radical thought shares an uneven but living relationship with radical action. If Adam Smith’s Dinner inspires people, it’s not clear to what exactly it will be. But I’d like to find out.