When Harry Crews was 16, scraping through high school with the dream of someday becoming a novelist, he decided it was time to meet a real writer, face to face. He selected Frank Slaughter, a bestselling author of historical fiction, who wrote books with titles like Buccaneer Surgeon and Devil’s Gamble: A Novel of Demonology. Crews hitchhiked 110 miles south to Florida from his relatives’ place in rural Bacon County, Georgia, found Slaughter’s number in the Jacksonville phone book, and called his house to arrange an appointment. But Slaughter’s wife answered the phone, and informed Crews that the author was out getting a haircut. He immediately turned back around for Bacon County.

“I mean, writers don’t get haircuts,” Crews said later. “I just couldn’t put together my own love of literature—the mystery, the overwhelming, profound, grandness of literature—with going to the barbershop and getting your hair cut.”

Over the next six decades, Crews made himself into the kind of writer that you could sooner imagine setting himself on fire than sitting quietly for a haircut. He cultivated an image as an outsized, Bacchanalian figure, the Lord Byron of the Okefenokee swamp, devoted equally to the arts of letters and partying. By the time of his death in 2012, Crews had published 15 novels, several collections of nonfiction, and a memoir. With his dark, often satirical writing, he had become a cult hero in certain circles, earning admiration from an odd mixture of literary and Hollywood heavyweights, including Madonna, Francis Ford Coppola, Sean Penn, Barry Hannah, and Norman Mailer.

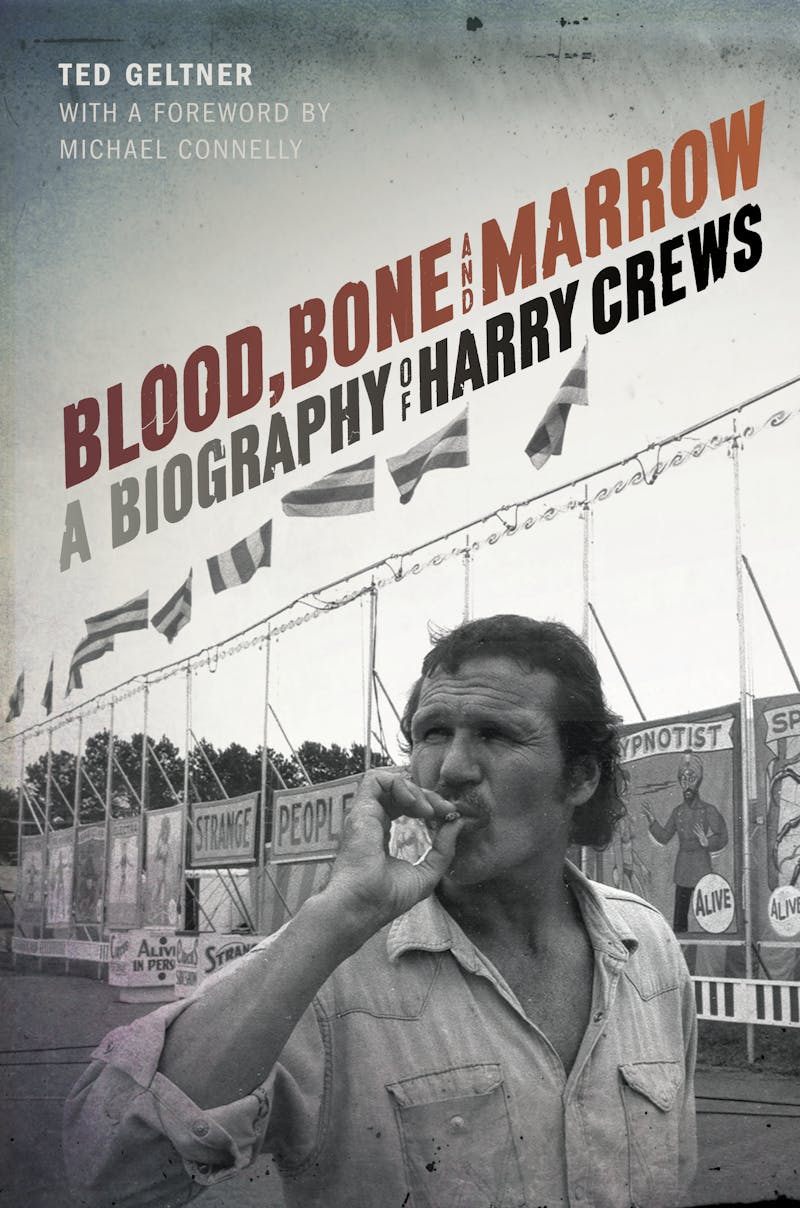

But, as journalist Ted Geltner demonstrates in Blood, Bone, and Marrow, his clear-eyed biography of the author, Crews’s most enduring character was himself. Just fact-checking the outlandish stories about Crews’s behavior must have been daunting work. (No, he didn’t hike all the way from Georgia to Vermont to show up at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, but yes, he did once list services from a prostitute and a tattoo parlor as “business expenses” while on assignment for Playboy.) Geltner’s biography, the first of any kind on Crews, manages to unearth the writer from the accumulated crust of legend and rumor.

Born in 1935, Crews grew up the son of a tenant farmer in, as he called it, the “worst hookworm and rickets part of Georgia,” and suffered through a childhood marked with tragedy and terror. His father died before he was two years old; when he was five, Crews contracted polio, and not long after his recovery he fell into a vat of boiling water, burning almost all of the skin off his body. Geltner dutifully covers Crews’s early life, but his retelling is, unsurprisingly, no match for A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, Crews’s searing memoir about his first seven years that represents the peak of his storytelling prowess.

When Crews begins to pursue his literary ambitions—after a stint in the Marines and a period working at a ketchup factory in San Francisco while hanging around beatnik bars trying to get Kerouac to talk shop—Geltner’s portrait of the author gains steam. Enrolled in the University of Florida, Crews studied under the literary legend Andrew Lytle, a spokesman for the Southern Agrarian movement and one of Flannery O’Connor’s favorite teachers. Lytle became a father figure for Crews, and he fostered in him the idea that writers were a class apart from other people. At one dinner at a fancy restaurant, Lytle, sensing Crews’s discomfort with the elegant surroundings, picked up his soup and slurped it from the bowl. “Remember son, we’re better than they are,” Lytle told Crews. “We’re writers.”

Through graduate school and during several years teaching English—first at a middle school and then at a junior college in Fort Lauderdale—Crews applied himself feverishly to the task of refining and submitting his work, until William Morrow finally bought his manuscript for The Gospel Singer, a novel about a faith healer returning to the tiny town of Enigma, Georgia with violent consequences. Over the next eight years, Crews would publish seven more books reflecting his different obsessions, among them learning karate, training hawks, and rounding up rattlesnakes. Almost every morning that he was not too hungover or inebriated to function, Crews would wake up at 4 a.m. and try to grind out 500 words on a new story. “Put your ass on the chair,” was Crews’s operational mantra.

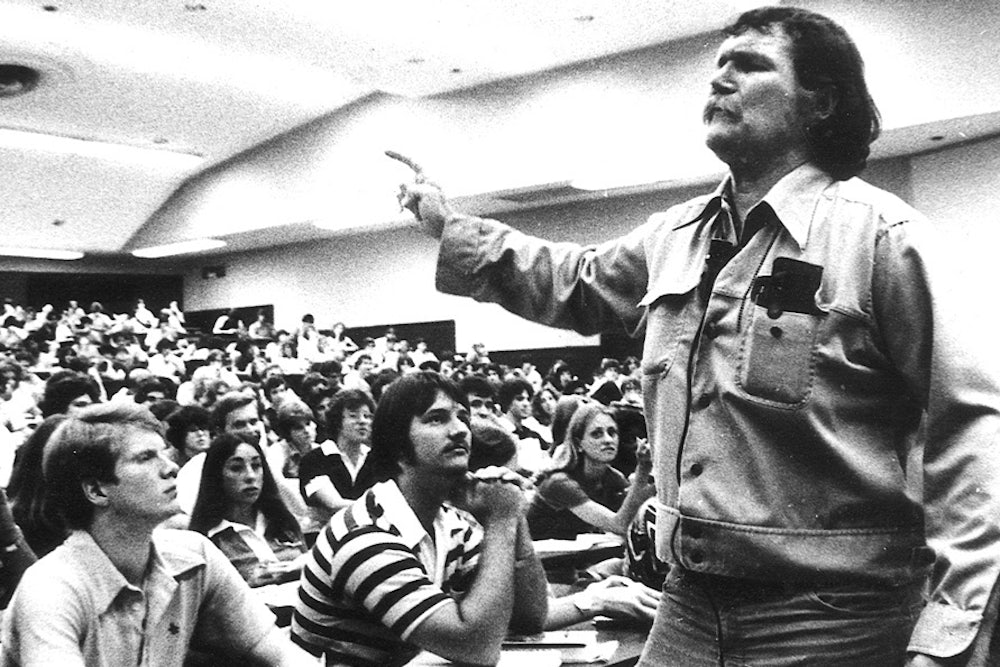

His dogged, near religious dedication to writing fiction was paralleled only by his devotion to getting completely ripshit. Crews managed to parlay the publication of The Gospel Singer into a job as an assistant professor at the University of Florida, a position he would hold for the better part of 30 years. The move to Gainesville and the success of his first novel exacerbated Crews’s worst tendencies. Crews had married—then divorced and re-married—Sally Ellis, a fellow student from his undergraduate days. Their marriage, which had survived the tragic drowning of their eldest son, Patrick, soon fell apart, brought to the breaking point by Crews’s constant drinking and sleeping around. Without the structure of family, beholden only to the gods of fiction and the remarkably understanding administration at the University of Florida, Crews’s life became an endless series of bacchanals and bar fights.

The “crazy party” stories in Blood, Bones, and Marrow—the time Crews showed up drunk at his lecture dressed as a gorilla, the one where he broke up with a woman by peeing inside her car, that day he passed out in a pool of vomit in the faculty lounge—begin to blur together after awhile. Through the fog of alcoholism and self-destruction, what comes into focus is his remarkable output. This was thanks in no small part to the women in his life, including his ex-wife Sally and long-term girlfriends Maggie Powell and George Kinson, who cleaned Crews up, typed out his longhand manuscripts, and kept him out of harm’s way as best they could.

Crews would regularly get involved with his young students. As one ex-girlfriend put it to Geltner, “he destroyed the lives, psychologically, of a lot of people.” And yet, the author was still capable of immense generosity—he cut a $1,000 check, unbidden, to help one of his students through a semester of graduate school. Even in his worst days, his classes drew long waiting lists, and his sheer, unwavering ardor for literature inspired a generation of U.F. grads. Though Crews was a champion bridge burner, he managed to attract a crew of followers and fans. His brand of wild-man charm is evident throughout Blood, Bones, and Marrow. Even after all the unflattering stories, you’d still like to get a beer with Crews (though perhaps not two).

Geltner is himself one of those followers. During the last four years of Crews’s life, when Geltner was working at The Gainesville Sun, he developed a friendship with the author. Crews, who had by then largely traded the bottle for prescription painkillers, had been ravaged by decades of hard living. After years of crashing in one spare room or another, Crews didn’t even have copies of his own out-of-print early work. Barely mobile and in worsening pain, Crews depended on Geltner and a small crew of acquaintances to ferry him on errands.

Throughout the book, an obvious warmth for his subject shines through, though Geltner doesn’t let it interfere with the thoroughness of his reporting. If there is a fault in Blood, Bones, and Marrow, it might be that it is a bit too thorough—reading it, you sometimes wish Geltner had excised passages about outside players in the Crews story to get back to the main event. It’s a small complaint for a work that does real justice to a complicated, outsized literary figure.

Crews kept writing until close to his final days. At one point, after he lost the use of his legs, he dragged himself by his arms to the keyboard to make his 4 a.m. appointment, chastising a houseguest, who wandered in at 7 a.m. for coffee, about being a late riser. But he had ruined relationships with several publishers and more or less severed his ties with the university he had taught at for 29 years. He found that more people wanted to hear about his drinking days than read his fiction.

When you build a persona with that kind of gravity, it takes a lot for your writing to reach escape velocity. “Most people are more interested, it seems, in talking about what I’m supposed to have done … than they are interested in my books,” Crews told an interviewer late in life. “It’s a mistake I started making early, and I never knew it was a mistake until it was too late.” At times, Geltner is one of those people; he certainly devotes as much ink to Crews’s antics as to his actual writing. But the intersection of career and personality is a complicated place. Trying to separate the conjoined twins of Harry Crews, the shit-kicking, vodka-swilling legend, and Harry Crews, the person, is a delicate, messy operation. Blood, Bone, and Marrow manages to do it without either dying on the table.