Once, in my youth, I took a graduate

philosophy seminar I thought would be about law and justice: Instead we discussed

the semantic implications of punctuation marks. After class, I found myself venting

to a friend who’d been a literature professor. I told her I was unsatiated by

the course—it felt like when I had discovered poetry and found, in practice, this

most lyric of arts often meant writing about flowers or describing an epiphany

in the grocery store checkout line. My friend laughed. “You know your problem?”

she said. “You thought that philosophy would be Truth and poetry would be

Beauty.”

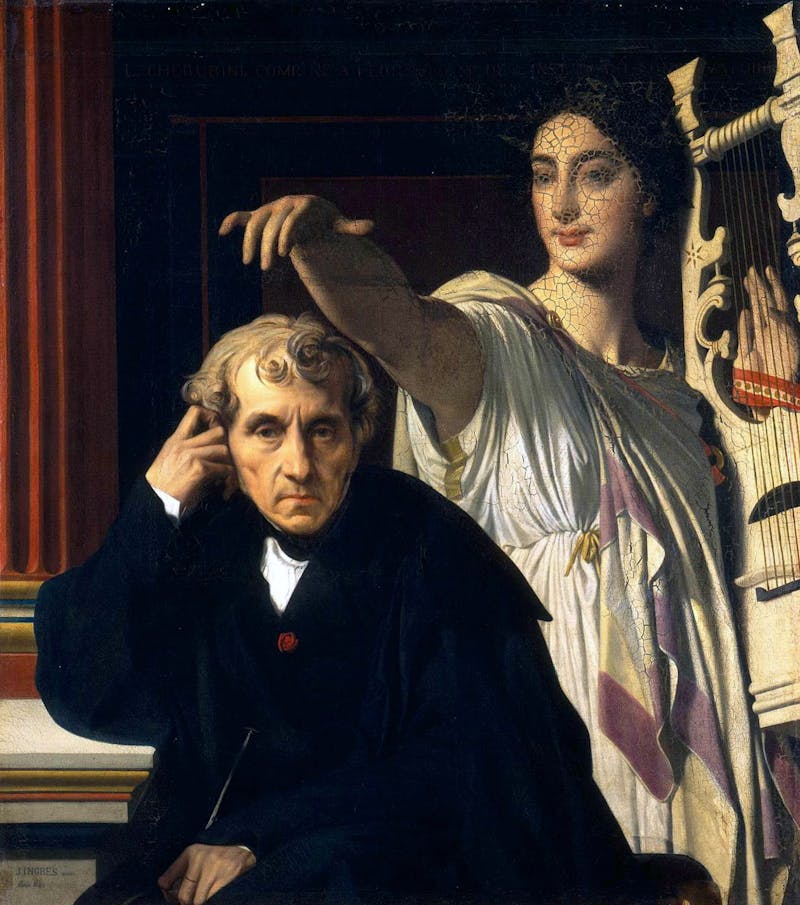

Apparently, this is Ben Lerner’s problem too. In his new book, The Hatred of Poetry, the poet, novelist, and MacArthur “genius” argues that if you love poetry’s promise of transcendence, you must also hate poems for their failure to keep up their end of the bargain. “Poetry,” Lerner writes, “arises from the desire to get beyond the finite and the historical—the human world of violence and difference—and to reach the transcendent or divine.” The only problem? Poems are ultimately human rather than divine in character. “As soon as you move from that impulse to the actual poem,” he continues, “the song of the infinite is compromised by the finitude of its terms. In a dream your verses can defeat time… but when you wake… you’re back in the human world with its inflexible laws and logic.” In other words, if you’re a poet, you may declare yourself the unacknowledged legislator of the world, but you’re really just a hobbyist in the verse game.

The Hatred of Poetry is a beefed-up version of Lerner’s 2015 London Review of Books essay, which he expanded to include a chatty tour of the Western tradition, from original poetry-hater Plato, to John Keats, Emily Dickinson, and Walt Whitman, and concluding with contemporary poets Amiri Baraka and Claudia Rankine. What’s nice about Lerner’s book is how it provides an occasion to discuss issues at the heart of mainstream poetry. He assesses the gains and the costs of poetry’s metaphysics and asks how lyric poetry can negotiate with the politics of real life, rather than Truth and Beauty.

I read The Hatred of Poetry as a referendum on the lyric, at whose altar Lerner worships, and which I find, to use the language of post-structural hermeneutics, kind of gross. While I may happen to disagree with Lerner’s often-conservative account, he is unique among contemporary poets for holding out a poetics and a position, which he discusses with remarkable amiability.

In Lerner’s account, poetry is the perfect medium for failure. Even great poems, he claims, perform this failure by suggesting the transcendent in their absence. “You can only compose poems that, when read with perfect contempt, clear a place for the genuine Poem that never appears.” John Keats may have coined poetry’s most famous slogan—“Beauty is truth, truth beauty”—but as Lerner points out, Keats also thought poetry’s unheard melodies were even sweeter. Emily Dickinson echoed this preference for the abstract when she proclaimed, “I dwell in Possibility” and Lerner’s central forerunner for the failure of poetry is Walt Whitman, whose democratic inclusiveness he describes as too utopian for the real world.

But even great poets, Lerner

suggests, yearn for divine possibilities they fundamentally cannot grasp—transcendence

cannot be accessed on our dismal human plane. One consequence of this is that

Lerner spends much of the book accusing poems of not possessing a quality that

he claims is impossible to possess, rather as one might gripe about never

having been visited by Santa Claus, while simultaneously lecturing that he is,

of course, not real. The book’s dominant

affect then isn’t hatred, but a mischievous, frustrated embarrassment.

To begin, Lerner imagines himself

being asked about poetry by a fellow passenger on a plane: “If my seatmate in a

holding pattern over Denver calls on me to sing, demands a poem from me that

will unite coach and first class in one community, I can’t do it.” It was at

this point in the book (page thirteen!) that I realized that I hate poetry

significantly more than Ben Lerner does, never having felt permission to aspire

to such heroic corniness. So what is one to make of this contrived scenario,

which incidentally embodies the book’s tonal oscillations between high-falutin’

and party-pooping? What does it mean to lament one’s failure to rise to an occasion

that has zero probability of happening? And is being asked to break into song

really something that happens on Denver-bound flights? I couldn’t help but picture

Ben Lerner as a Jenna Maroney-style chanteuse, biding his time until he’s

asked onstage at a karaoke bar, only to refuse—he’s too compromised by his own

ontological finitude! Lerner wrote a similar scene in his 2010 poetry collection Mean Free Path, where the speaker breaks

off from a soliloquy to say “You’re not listening.” Another speaker replies:

“I’m sorry. I was thinking / How the beauty of your singing reinscribes / The

hope whose death it announces.” That’s Hatred

of Poetry condensed into a sentence. But take a moment to look at Lerner’s

self-aggrandizing language here, language no one would ever say. It takes a

true believer to describe poetry (let alone your own poetry!) as “the beauty of

your singing.” The problem then isn’t

that Lerner hates poetry—it’s that he’s too credulous of its claims.

Mean Free Path is the last collection of poetry Lerner wrote before jumping ship to the novel, publishing Leaving the Atocha Station in 2011 and 10:04 three years later. Both are diary-like narratives that riff on the impossibility of poetry. Reading The Hatred of Poetry, one feels that Lerner left poetry behind because the novel—the medium whose embrace of the quotidian and the accidental led Milan Kundera, in The Art of the Novel, to praise it as “antilyrical poetry”—permitted him to rhapsodize without feeling the poet’s claustrophobic responsibility to speak for Truth and Beauty. Perhaps his work as a poet allowed Lerner to experience his own profound and perhaps turbulent inner life in the novel. As the protagonist in Leaving the Atocha Station admits, “I had long worried that I was incapable of having a profound experience of art, and I had trouble believing that anyone had, at least anyone I knew.” You get the sense Lerner’s intellectualized peevishness about poetry is simply an elaborate defense, one that distances an author from the shame, discomfort, and vulnerability that comes from experiencing one’s own emotions.

Every age finds itself motivated by reactionary desires. It is perhaps no accident that Keats’s Romanticism, animated by an Arcadian fantasia of Grecian urns, Elvan forests, and intangible truths, manifested itself alongside the grimy sweatshops of the Industrial Revolution. In our own time, we conduct disembodied work over the internet, but are sold images of ourselves as laborers in the form of selvage jeans, rusted typewriters, wood crates, and other gewgaws of bygone Americana. I suspect that many readers attend to mainstream American poetry as seekers of a secular faith. Poetry is meaning itself!

Transcendence is an old-fashioned way to name poetry’s virtues, and The Hatred of Poetry is an old-fashioned book, one whose chatty manner hides its conservative account of poetry as spiritualism under another name. The book starts mischievously but ends happily. In the last few pages, Lerner admits that (spoiler!) he finds himself deeply moved by all kinds of everyday moments: watching outdoor community theater, glimpsing the fleeting light of fireflies, or seeing endless rows of Cap’n Crunch cereal—which, in case you were wondering, he describes as “sugary infinities.” The alienated skeptic has returned to the flock.

But glance back to Lerner’s hypothetical encounter on the plane and you’ll notice the curious role he assigns poetry: To “unite coach and first class in one community”—in other words, a political project of social cohesion. The Hatred of Poetry’s title and its earnest metaphysics belie the fact that it presents not just Lerner’s poetics, but also his politics.

Lerner begins the second half of his short book attacking the avant-garde poets of the early twentieth century, those who hate poetry rather too much, and contemporary cultural critics, who may love poetry too much—or rather, a certain nostalgic view of it. The historical avant-garde casts a long shadow of Modernism across the century, one that more conservative poets still labor beneath today. Lerner’s “aggressively cursory” critique zeroes in on the Italian Futurists, helmed by Filippo Marinetti, whose quotations provide the book’s only real jolts of rage, fury, and nihilism. According to Lerner, avant-garde poets want poems to be “an instrument of war in a heroic, revolutionary struggle.” Since the revolution never comes, Lerner argues that these erstwhile radicals are left to “hate poems for remaining poems instead of bombs.”

Lerner then rebuts George Packer, writing in 2008 about poetry presented at presidential inaugurations for the New Yorker, and Mark Edmundson, writing in 2013 on contemporary poetry for Harper’s, who both want American poetry—currently written in a personal, idiosyncratic, subjective mode—to respond to the concerns of the larger public. Today’s poems, Edmundson bemoans, “don’t slake a reader’s thirst for meanings that pass beyond the experience of the individual poet and light up the world we hold in common.” While Lerner’s arguments against Edmundson are more complicated, as we’ll see, he generally accuses these critics of wanting poetry to return to a golden age that never actually existed. Lerner characterizes the avant-gardists and these cultural critics as opposites, but says they’re actually both driven by the same emotion: “anger at poetry’s failure to achieve any real political effects.”

Surely, one would want any art form to possess at least some political facets, but Lerner has his misgivings, despite having written about the War on Terror in his poetry collection Angle of Yaw and Occupy Wall Street in 10:04. He argues that the “defensive rage” of these haters constitutes a “reaction formation”: They’re just bitter about poetry’s lost transcendentalism, despite the fact that neither the avant-garde, Packer, or Edmundson seem engaged in Lerner’s project. Merely disliking poetry, Lerner presents himself as a voice of reason, one who can moderate these excesses and defend the art against the pollution of politics. It’s curious to see what he doesn’t do: argue for a political project that he might prefer.

I read the second half of Lerner’s book not just as a manifesto against political poetry, but as something stranger and more ideological. In his attacks on the avant-garde, Lerner paraphrases Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde. Bürger’s theory—which is mind-blowing if you’ve ever thought that avant-garde artists aspire to be as pretentious as possible—is that these experimental artists simply wanted to bring art closer to life. This means telling your readers to get drunk (as Baudelaire did), quoting ragtime and commercial jingles (T.S. Eliot), installing a urinal in an art show (Duchamp), or admitting the burbling noises of the street into the concert hall (John Cage). These may be assaults against art, but they’re also embraces of life.

But if you believe in poetry as a pure sanctuary beyond us mere mortals, what could be more repellant than iconoclasm, chance, and mass culture? Modernism sought to debunk metaphysical foundations for the truth, which so many philosophers cast as a pernicious illusion and distraction from human life. The charge Lerner levels against both futurist and cultural critics is the opposite: their seemingly improper desire to “enter history.” This is a strange criticism that grows more legible if you remember that Lerner thinks the point of poetry is to offer refuge from “the finite and the historical—the human world of violence and difference.” This passage gave me pause, as I am a poet who rents a too-expensive one-bedroom apartment located within the human world. While avant-garde poetry is usually framed as a nihilist assault against lyric poetry, we can now see that the opposite is true: What is most offensive about avant-gardism is its attempts to bring human messiness and excess into a medium that is against humans, lyric poetry. Read this way, The Hatred of Poetry is a betrayed valentine to poetry, one that doesn’t so much dismantle its divinity as expresses annoyance over the pesky humans that get in its way.

Lerner spends much of his book discussing the ideal poet: one who can “unite us in our difference, constituting a collective subject through the magic of language and prosody, one who, by speaking for herself, could speak for every self.” (Lerner himself seems to yearn for this role: His authorial stand-in in 10:04, a poet-novelist named Ben, considers becoming a father and admonishes himself, “What you need to do is harness the self-love you are hypostatizing as offspring… and let it branch out horizontally into the possibility of a transpersonal revolutionary subject in the present.”) But Lerner admits the “implicit politics [of such universalism] make me uneasy.” By this, he means the tendency within Western humanism to assume the universal subject a white heterosexual male. Lerner critiques Edmundson for declaring that a white dude like Robert Lowell can speak for all humanity but that Sylvia Plath can only speak for women. Against the universal self, Lerner considers poets Amiri Baraka and Claudia Rankine as writers who carve out a particularized black self, and he presents an inspired reading of Walt Whitman, who Lerner takes as the paradigmatic, but unsuccessful, poet of American radical inclusivity.

More than a year after September 11, Amiri Baraka released his furious, controversial poem, “Somebody Blew Up America.” “Somebody” became infamous for its lines suggesting that Israeli workers in the Twin Towers received advance warning about the attacks, suggesting for many that Baraka believed in a worldwide Jewish conspiracy. Edmundson calls it one of the few “large-minded poetic response[s]” to 9/11, “an attempt to say not how it is for Baraka exclusively but how it is for all.” Lerner disagrees. He quotes a speech Baraka gave defending himself from charges of anti-Semitism in which Baraka says that the poem thematizes “our history”—the history of “how Black Americans have suffered from domestic terrorism” at the hands of chattel slavery and Jim Crow. That means that when you read the poem as speaking for “all,” Lerner argues, you “tactically forget the history of anti-Black violence” and “repeat the dismissal of ‘our [people of color’s] history.’”

Lerner seeks to critique a universalism premised on whiteness, but his politically correct reading erases Baraka’s more radical program, diminishing him into a digestible flag-waver for diversity. “Somebody Blew Up America” is an anti-matter “Song of Myself,” a maximalist litany about everyone who’s ever been annihilated by or opposed American imperialism:

Who need fossil fuel when the sun ain’t goin’ nowhere

Who make the credit cards

Who get the biggest tax cut…Who locked up Mandela, Dhoruba, Geronimo,

Assata, Mumia, Garvey, Dashiell Hammett, Alphaeus Hutton…Was it the ones who tried to poison Fidel

Who tried to keep the Vietnamese OppressedWho put a price on Lenin’s head

Who put the Jews in ovens,

and who helped them do itWho said “America First”

and ok’d the yellow stars

The poem speaks on behalf of oppressed colonial subjects (Indigenous peoples, Palestinians, Pan-African leaders), Western state leaders (Lincoln and Lenin), black activists (Garvey, Huey Newton, Mumia), and white communists (Rosa Luxemburg, the Rosenbergs, Dashiell Hammett). When Baraka gave a speech about the controversy over the poem—and refused to resign as New Jersey’s poet laureate—he delivered a raucous denunciation of Nazism, Zionism, McCarthyism, capitalism, and the War on Terror. Despite Lerner’s characterization of the speech as exclusively about black identity, Baraka wrote out of a more expansive lineage of anti-capitalist radicals who saw their blackness as only one part of a worldwide resistance against American empire, like W.E.B. Dubois, who toured China to learn about socialism, and Malcolm X, who lobbied the UN, hosted Fidel Castro, and called himself a citizen of Asia in protest of the Vietnam War.

Lerner spends much The Hatred of Poetry performing close readings of grammar, meter, and punctuation, but when he gets to Walt Whitman and Claudia Rankine, his formalist readings cordon him off from what the poems actually mean. Why is Whitman great? Lerner says it’s “the capaciousness of his pronouns.” When Whitman writes “you,” he encompasses everyone in this universalizing second person embrace, but Lerner points out that deploying “I” and “you” this way is too “perfectly exchangeable”; the words mean something entirely different if you’re a Confederate or slave.

Whitman’s correction, Lerner argues, arrives in Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, a book comprised of second-person accounts of racial trauma. “Citizen’s concern,” Lerner writes, is “with how race determines when and how we have access to pronouns.” After spending three pages discussing Whitman’s pronouns, Lerner spends another two pages (about half his Rankine discussion) talking about her pronouns, before moving onto a five-page discussion of her slashes. (The “technical term,” he informs us, is the “virgule.”) While not uninteresting, Lerner’s close reading of pronouns is really repressed race talk, a way of talking about “I” and “you” rather than “white” and “black.” A reader unfamiliar with their work might be forgiven for imagining Whitman and Rankine engaging in a century-plus-long Highlander-style duel over noun substitution, rather than asking what it means to be a citizen of the American racial project.

In his 1980 essay “Afro-American Literature & Class Struggle,” Baraka argued that such formalistic readings constituted political censorship. When you close read a poem, as Lerner does, you often end up spending more time talking about dashes than about, say, historical context, authorial intention, or politics. Baraka saw close reading as a strategy deployed by conservative Southern critics—he singled out so-called New Critics like John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren—to focus on style as a way to avoid talking politics. Throughout the book, Lerner constantly invokes politics, only to suppress actual political content. He reads under the shadow of twin ideologies that omit a poem’s content: That of the Romantic lyric, which imagines poetry as an art of pure spirit, and those critics who Baraka attacked for emphasizing formalist close readings of craft.

I suspect the failure Lerner identifies really arises from writing under these contradictions. The lyric asks the poet to unleash the volcanic infinity crackling within, but upon close reading, such sublime magma cools into a belabored mastery. Lerner writes at one point that “actual poems are structurally foredoomed by a ‘bitter logic’ that cannot be overcome by any level of virtuosity”—but this gets the relationship backwards: It is virtuosity itself that leads to the diminution of poetry from sorcery into mere technique.

Citizen isn’t powerful because of its grammar—it’s powerful because Rankine implicates the reader beyond the text. When reading Citizen, you have no choice but to either recognize prejudicial behavior you have committed, or recognize racial trauma you have suffered. What the book does—with its bright-white, acid-free pages of rectangular sans serif type—is slap curatorial wall text onto these lived experiences of racial trauma. Lerner does write that the book makes him “aware of how I, a white man, cannot in fact relate to the experience in question; I cannot be a victim of such racism.” This inward guilt about white privilege reminded me of a scene in 10:04 where the protagonist ruminates on the Latino restaurant staff serving him and can’t help but think that his publishing contract advance nearly matches their lifetime salary.

Lerner writes that “to claim [Citizen] as lyric would baffle Keats,” simply because the book is written in prose. But the book’s engagement with the lyric is deeper and more political. Rankine’s speaker often daydreams of clouds—a floating image of transcendence straight out of Wordsworth—but this ruminating private self must also wake up and assume the role of the citizen, the exhausted black body whose social interactions are over-determined by the legacies of the American slave state. Lerner may refuse a poetry that speaks for all, but one of Rankine’s lessons is that no matter how much you want to introspect, you’re still stuck assuming your role as a “historical self,” a player in the rigged game of white supremacy. Lerner argues that Rankine feels “the unavailability of traditional lyric categories,” but I think Citizen’s doubts are less literary than political. There’s no one in Citizen singing, “We Shall Overcome.” As in Ta-Nehisi Coates, Rankine sees little salvation in the prospect of emancipation from racial inequity.

Similarly, what mattered about Whitman wasn’t his pronouns, but who they named: a cosmos of citizens and workers, such as runaway slaves, blue-collar laborers, Arab Muslims, and other people considered too abject for American democracy then and now. In 10:04, Lerner has his protagonist provide an alternate characterization of the poet:

Whitman, because he wants to stand for everyone, because he wants to be less a historical person than a marker for democratic personhood, can’t really write a memoir full of life’s particularities. If he were to reveal the specific genesis and texture of his personality … he would lose his ability to be “Walt Whitman, a cosmos.”

While this is not untrue, Lerner talks as if Whitman’s project was one of messianic autobiography—but the reason Whitman does not present his own particularized historical self is far simpler: He’s not writing autobiographical lyric poetry. What’s so lovely and unusual—and to today’s reader probably tiresome and extra-literary—is Whitman’s loving desire to name every living creature of the world. (“The Pennsylvanian! the Virginian! the double Carolingian!”) Against these wild, rhizomic, pluralistic poems, Lerner says that Whitman stands for “contradictions of a democratic personhood that cannot become actual without becoming exclusive.” Lerner then characterizes Whitman’s project as impossible: “You don’t need me to tell you that Whitman’s dreamed union has never arrived.” To be honest, I wasn’t entirely sure what Lerner meant here, but I got the feeling he was disappointed that Whitman lacked the mutant superpower to occupy several bodies at once, rather like Hobbes’s Leviathan, or Voltron. Lerner reads Whitman as a one-person stand-in for the transcendental, but Whitman cared more about our world than another purer one waiting for us beyond (“The Mexican muleteer”! “the Arab muezzin”! “the cry of the Cossack”!). What Lerner wants is a writer who’s transcendentalist enough to be everyone, rather than one politically creative enough to imagine the world’s oppressed—someone, in other words, like Amiri Baraka.

The strangest takeaway I had from writing this essay was the startling realization that Ben Lerner believes more in identity politics than Amiri Baraka did. For Lerner, political poetry is impossible, unless you are a black poet who speaks for black people or a unicorn like Walt Whitman, who speaks for everyone, but should probably check his privilege. If Lerner hand-wrings over how much more money he makes than a Latino restaurant worker, if reading Citizen makes him feel guilty, then his political horizon only extends as far as noticing the insufficiency of his own self. We may think of Baraka as a Black nationalist, but the deeply internationalist poet shifted to Marxism in the mid-seventies. (“It’s not white people who are the enemy,” he once told Rutgers students. “The wealthy are your enemy.”) His political program was a Third World Marxism that incorporated the insights of 1970s black radicals, historians like the recently deceased Cedric Robinson, who showed capitalism’s essentially racial character, and Pan-African socialists like Léopold Senghor of Senegal. If Lerner was actually interested in a political society imagined by poets, he might consider Senghor and those other left poets who fought colonialism and ended up becoming heads of state, like Amílcar Cabral, Hồ Chí Minh, and a little known cultural revolutionary named Mao Zedong. These poets didn’t see poetry and politics as an impossible intersection, and neither did Baraka, who organized Newark’s first Black Power conference, founded the Committee for a United Newark, and strategized to elect the city’s first black mayor, Kenneth Gibson. But The Hatred of Poetry is deformed by Lerner’s transcendentalism. The book offers no politics, since politics can only take place in the human world.

Do people actually hate poetry? Lerner doesn’t

really answer this question. In the end his book is an account of the special

love-hate relationship that poets have with their art. What’s missing here is

political economy. Poetry retains some old world prestige, the stuff of Shakespeare

in the park and college seminars on Modernism, which is why some poetry fans

see it as one of civilization’s last bulwarks against supposed barbarism. But

if appreciating poetry marks your class attainment, then poetry also ends up

being exclusive. It’s stuffy and inaccessible, when it’s called poetry, but not

when it’s called stand-up comedy, Weird Twitter, hip hop, flash fiction, or

spoken word. And then there is the class mismatch between poetry itself and

those who practice it. To be a poet now often means being a penniless adjunct

professor, and its hard to see a poet as a visionary hero if they are also

working for minimum wage with worse health benefits than a Starbucks barista. Hence

the contradictory predicament of contemporary poetry: Poets make no money, but

poetry itself is sneered against as an antiquated curio of old money

connoisseurs.

And there’s the bigger problem—namely, that we live in a world governed by the twinned ideologies of science and capitalism. If lyric poetry is conservative because it stands for transcendence, then believing in its sacred domain also means believing in a space untouched by rational explanation or commodification. In Lorrie Moore’s short story, “Terrific Mother,” the main character visits an artist colony, which it turns out is plagued by an insufferable “poetess.” Her poetry is rife with twee and obnoxious metaphors: one consists of the repeating line “the hairy kiwis of his balls” and she keeps referring to insects as “God’s typos.”

Lerner would probably think the ridiculousness of these lines proves his thesis, but I think we find them embarrassing for a different reason: because their intuition seems like an avoidance of life, substituting sex and divinity with whimsy. In another age, philosophers revolted against God, and we live in the post-Enlightenment world they created. “God’s typos” is a perfect example of poetry’s perceived quaintness, reaching as it does towards religion but without religion’s conviction in an era after the death of God. Where anything that exists can be manufactured, indexed, branded, and sold, poetry can seem embarrassing—the last refuge of magic in a world that has been disenchanted.