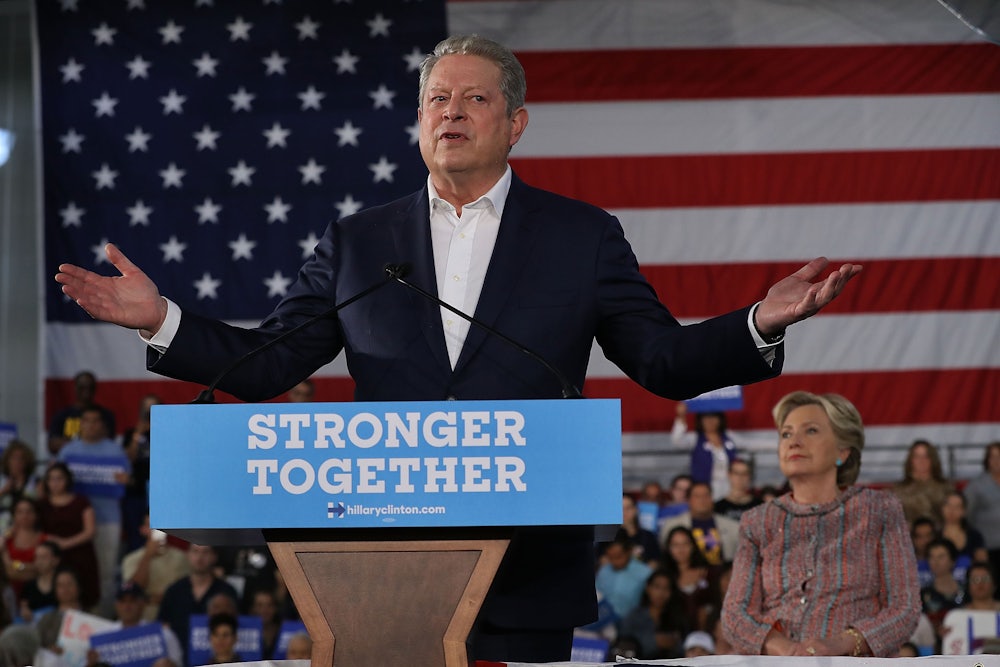

At a campaign rally in Florida on Tuesday, Al Gore and Hillary Clinton spent a whopping 46 minutes on climate change—the most attention given to the issue so far in the general election. But for many media outlets, the news hook wasn’t that the star of An Inconvenient Truth was bolstering Clinton’s environmental bona fides in a state battered by climate change; it was his reminder that “every single vote counts”—that a protest vote for a third-party candidate could lead to a Trump presidency, just as Ralph Nader voters in Florida secured George W. Bush’s defeat of Gore in 2000.

This is par for the course for climate change’s profile in the 2016 election. The subject was discussed for just 325 seconds over the first two presidential debates—and even then, it wasn’t about climate change per se. During the first debate, Clinton noted that Trump once said climate change was invented by the Chinese. Trump lied, saying, “I did not.” During the second debate, an audience member asked, “What steps will your energy policy take to meet our energy needs while at the same time remaining environmentally friendly and minimizing job layoffs?” No one remembers the answer—because the questioner in the sweater, Ken Bone, became an internet meme.

All of which is to say, climate change is once again taking a back seat in a presidential election—and activists and journalists are a bit despondent about it.

“A lot of environmental reporters are asking, ‘When are we gonna talk about it? Is it time?’ I feel like all of us are like, ‘Maybe this is our year!’” said Kate Sheppard, a senior reporter at The Huffington Post. “There’s even a running joke where, when we’re all watching the debate and climate change comes up, we’re all saying, ‘I finally get to write something!’”

Indeed, 2016 was supposed to be different. This year was “the climate change election,” as headlines in Slate, Salon, and U.S. News declared. But now, with only 27 days until November 8, it’s safe to say that this wasn’t a climate change election after all.

“I think we thought this year should be the year for climate change because of the Paris Agreement, because this is the hottest year on record, because there have been extreme weather events, and the arctic is shrinking,” said Oliver Milman, an environmental reporter at The Guardian. “There’s a whole range of reasons it should be a topic this campaign, but it’s not.”

There’s a whole range of reasons it’s not, too. This election is defined first and foremost by Trump. His behavior, past and present, is so consistently outrageous that it seems to dominate every news cycle, drowning out discussion of myriad policy issues, climate change included. Debate moderators, in turn, have focused on Trump’s offensive remarks and extreme positions—and when it’s Clinton’s turn, they tend to focus on her emails or the Clinton Foundation.

But there may also be a deeper, psychological reason for the short shrift given to climate change.

“It’s human nature to prioritize immediate problems over future problems,” said Rebecca Leber, an editor at Grist. “Politicians often frame climate change as a future problem, and of course it rates lower on your priorities if you think it’s something that doesn’t need to immediately be addressed.”

And when climate change is framed as an immediate problem by politicians and journalists alike, it’s often by linking it—sometimes spuriously—to headline-grabbing natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods.

“What we have seen happen in the past, and what we might be seeing happen here, is that conversations about climate change are driven by an extreme weather event,” Leber said. “For climate change to become an election issue, we will probably see and feel the impacts of climate change—and not only that, but be able to connect extreme weather to climate change, and not as an isolated event.”

It isn’t easy to pin down voters on the issue of climate change. On the one hand, polls consistently show that a majority of American adults are worried about global warming. On the other hand, polls show that climate change ranks near or at the bottom among issues of most importance to voters.

The disconnect is partly due to partisanship. Among all issues, climate change has the greatest gap between Republican and Democratic voters in terms of its importance to them—72 percent to 25 percent, according to Gallup. If most Republicans don’t care about climate change, and most Democrats do, no wonder the issue hasn’t gotten much attention on the campaign trail.

That leaves activists and reporters feeling ... a range of emotions. RL Miller, president of Climate Hawks Vote, a super PAC, said it feels like “she’s shouting into the wind” when she tries to reach people on climate change. Shepherd said she’s become “too cynical” to assume climate change will get a question at a debate. And Milman said he finds it frustrating to repeatedly see a “woefully inadequate” response to climate news by voters and the media.

Despite this, reporters and activists are holding out hope for a “climate change election” in the future.

“It would be great to see this change, and maybe in 2020 we figure it out,” Leber said, “and climate change gets more attention and energy policy gets its own debate instead of being just a brief talking point.”

She added, “But that’s what people have been hoping for for decades, and we haven’t seen it.”